Chapter 51: Forest Management Systems – Download PDF

Author: Peter Spathelf

Author affiliations are given at the end of the chapter

Intended learning level: Advanced

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC-BY-SA 4.0.

|

Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

|

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce the variety of the current forest management systems with special consideration of the historic roots. |

NOTE: this text is a complete draft, which will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

51.3 Close-to-nature forest management (CNFM) 3

51.4 Integrated Forest Management (IFM) 4

51.5 Disturbance-Based Silviculture (DBS) 5

51.6 Functional Networks (FN) 5

51.7 Climate-smart forestry (CSF) 5

51: Forest Management Systems

Forest management systems (FMS) are more than silvicultural systems which are clearly defined as the alteration of the stand environment in order to regulate forest growth, stand structure and composition, thereby imitating natural ecosystem processes (Ashton & Kelty, 2018). FMS, in contrast, refer to any planned human intervention in a forest ecosystem to achieve specific goals and objectives, which can typically be grouped as environmental, economic, and social. FMS can include anything from low intensity to high intensity interventions using different practices, tools, and techniques. Their implementation is normally linked to the existence of a management plan.

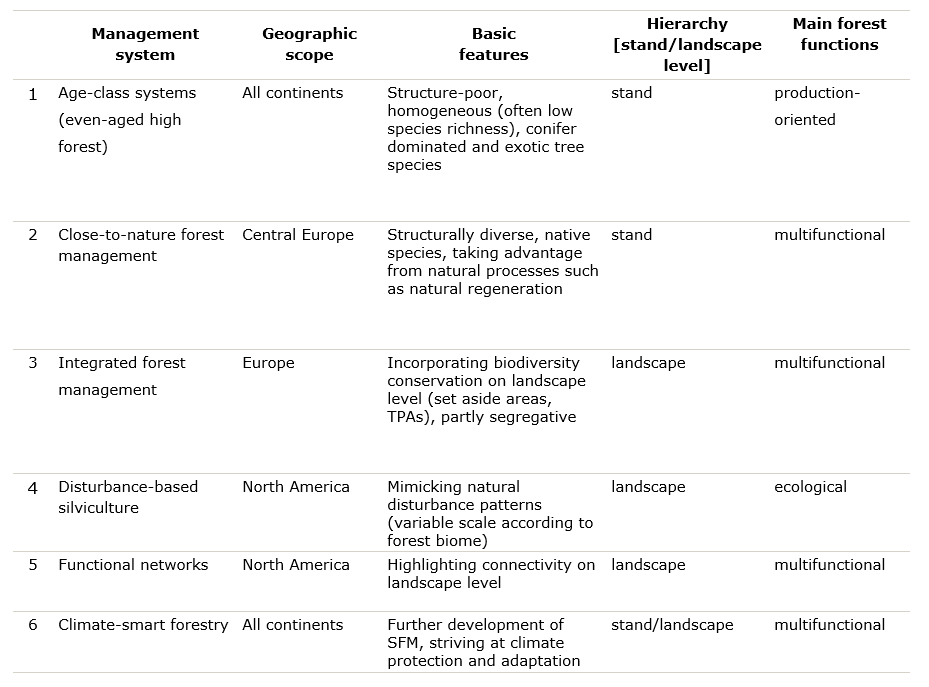

Since several decades, traditional production-oriented age-class forestry is more and more replaced by close-to-nature forest management systems or integrative approaches using natural processes. Moreover, the latter systems recently experienced refinements in anticipating global (climate) change through forest adaptation (e.g., climate-smart forestry) (Bowditch et al., 2020; Hahn & Knoke, 2010). Some of the systems mentioned in this chapter are clearly valid for the stand scale of forests (3.), others are related to the landscape scale (2. and 4.-6.). Some basic information on the presented management systems is described in Table 51-1.

Table 51-1: Basic information on management systems

The origin of age-class forestry dates back to the time before the 19th century, when irregular, selective logging was conducted. A dramatic increase in wood demand during the industrial revolution, however, led to an intensification of forest management and the introduction of forestry activities according to more agricultural principles, like soil tillage, fertilization and the spatial-temporal classification of forests into cutting sequences. In the early 19th century huge areas which were deforested and degraded since the Middle Ages were restored to forests. Thereby, mainstream forestry in Germany, but also in Scandinavia, France or the Netherlands laid an emphasis on even-aged high forests with a preference for clear-cutting (Pommerening, 2023; Thomasius, 1996). The forest model at the time was the age-class forest, the so-called ‘fully regulated forest’, leading to large-scale so-called monocultures of faster growing conifer stands with Norway spruce and Scots pine. In the 20th century, the dominance of age-class high forests was strengthened by rationalization and mechanization and the effective exclusion and management of disturbances, respectively.

51.3 Close-to-nature forest management (CNFM)

Over time many of these even-aged pure forests were lost due to an increasing number of pest attacks and abiotic damages; disturbances in the forest could no more be excluded. Consequently, the first Central European forest scientists started to recognise that pure (even-aged) stands may not be resistant and resilient enough for long-term economically successful forest management. One of the most prominent advocates of mixed forests at the turn to the 20th century in Germany was the silviculturist Karl Gayer, who strongly supported the irregular shelterwood system for stand regeneration (Heyder, 1986; Gayer, 1886). In the 1920s, Alfred Möller promoted the idea of continuous-cover forestry (CCF), called ‘Dauerwald’, which was a special variant of CNFM. He advocated single-tree oriented interventions, natural regeneration, avoidance of clear-cutting and the maintenance of multi-storied mixed stands (Helliwell, 1997; Möller, 1922). Other pioneers of CCF in Europe were Biolley (Switzerland and France), Mlinšek (Slovenia) or Ciancio (Italy). Thus, CCF systems comprise all silvicultural systems, which permanently retain at least a part of the canopy during management, especially regeneration (Pommerening & Murphy, 2004). Although first practised mainly by private forest owners, such as the members of ANW in former West Germany, CNFM emerged among all forest ownership categories during the last quarter of the 20th century. Thereby, forest owners responded to new environmental developments and challenges (e.g., forest decline), major disturbances (storms, insects) and the increasing scientific evidence that mixed forests may be more resilient and productive than pure forests Today, the ideas of CNFM are widespread in Central Europe and part of the programme of ProSilva (e.g., Brang et al., 2014; Knoke et al., 2008).

A central principle of CNFM is the utilization of natural processes to guide forest ecosystems with the least amount of energy input (costs) as possible. Other prominent elements of CNFM are (Pommerening & Murphy, 2004; Johann, 2006; Spathelf, 1997):

- promotion of natural and (or) site-adapted tree species composition (non-native species, if admixed to native species, are accepted to a small extent),

- promotion of mixed and ‘structured’ forests,

- avoidance of clear cuts, as far as possible,

- promotion of natural regeneration,

- single-tree oriented silvicultural practices,

- integration of forest ecosystem services (e.g., water, recreation) at small spatial scales.

CNFM is thus not a silvicultural system or technique in sensu strictu, but a broad approach with different elements which can be adapted to changing natural and socio-economic conditions (Spathelf, 1997). To date, CNFM in the described specification is mainly applied in Central Europe, but also relevant in other forests, such as in native American reservations or in plenter forests of Japan (e.g., Münzer et al., 2023). The practical success of CNFM depends on reduced impact of tending and harvesting on the remaining stand and soil (Reduced Impact Logging) and controlled ungulate populations. CNFM is an integrative approach of (sustainable) forest management (SFM) and biodiversity conservation on a small scale (Schütz, 1999). When classified according to management intensity, tree species and structural heterogeneity, CNFM occupies its place between selection and old-growth forests on the one hand, and forests after larger stand replacement events or even plantations on the other hand. This classification demonstrates the range of regeneration cuts and forest target structures which are feasible within CNFM.

The international terminology on CNFM is multifaceted and varies from ecological forestry, systemic silviculture to ecosystem management or retention forestry, depending on historic roots of the respective countries (see Puettmann et al., 2015, for an overview).

51.4 Integrated Forest Management (IFM)

In Central Europe, the majority of forest areas are managed and timber used according to economic criteria, while at the same time ensuring minimum requirements for forest nature conservation – an approach known as Integrative Forest Management (IFM) (Krumm et al., 2020) or land sharing. In segregated forest management (land sparing), on the other hand, there is a coexistence of strictly protected areas and intensively managed forests geared to economic requirements (e.g., pine plantations in Chile or the southeast of the USA). In IFM, specific forest services such as recreation, protection against natural hazards or provision of non-timber forest products, can be prioritised in sub-areas designated for use.

IFM is largely in line with the needs of adapting forests to climate change, as shown in a recent literature review by the European Forest Institute (de Koning et al., 2020). At the stand level, continuous cover forest is increasingly becoming the guiding principle of IFM. Compared to conventionally managed age-class forests, continuous-cover forests, e.g., in the form of plenter forests, are in many cases more resistant and more resilient (Diaci et al., 2017) to disturbances. Thus, permanent forest-like structures can probably partially buffer climate change-induced disturbance intensification. However, IFM is also criticised. There are calls for more segregative elements to meet society’s changing demands on the forest (e.g., nature conservation) (Borchers, 2010). A more segregative variant of IFM is the TRIAD system, in which the forest is divided into three separate zones of complementary functions, i.e., intensive timber production, multiple use forestry and biodiversity conservation (Krumm et al., 2020).

51.5 Disturbance-Based Silviculture (DBS)

Natural disturbance-based management or disturbance-based silviculture (DBS) originates from North America and pursues the primary goal of near-natural management at the landscape level by emulating the regionally prevailing disturbance regime (Aszalós et al., 2022). The concept is not directly aimed at avoiding disturbance, but rather seeks to specifically incorporate it into management, or to anticipate it. The species compositions and forest structures that develop as a result ensure high beta diversity. This results in a broad spectrum of possibilities for autonomous adaptation of the forest after disturbances. In order to implement DBS, information on the disturbance regime, including the range of disturbance inter, disturbance intensities and spatial extent of disturbance, is needed. Within this, disturbance-based silviculture favours highly variable management regimes, whereby one part of the landscape can also be used very intensively and thus imitate the strongest disturbances, whereas other parts are only managed very gently and thus imitate weak disturbances. The derivation of the natural disturbance regime is critical, as there are only few natural forests that can be considered as reference areas in Central Europe. Furthermore, disturbance regimes change due to climate change and thus the “natural” reference must be permanently adapted to new conditions (Aszalós et al., 2022).

Functional networks (FN) are defined by the functional diversity of stands and their connections with other stands (connectivity) (Aquilué et al., 2021). The length of the connections is the potential range of seed dispersal and the strength of the connections is the amount of functional diversity (i.e., the diversity of species traits that influence ecosystem processes and thus control growth, survival and regeneration) that can potentially be passed on. For example, the optimal temperature for photosynthesis varies between species, so competitive relationships shift with temperature changes. After disturbance, the transmission of functional diversity through the network ensures high ecological resilience and offers great potential for adaptation to climate change. To establish FN, it is therefore necessary to create stands with high functional diversity that are connected to each other through seed dispersal. The limitations for the practical application of FN result from the lack of knowledge and the difficult definition of functional diversity. In general, it can be stated that a good mixture of early and late successional species, as well as of conifers and deciduous trees, ensures a high functional diversity (Thom et al., 2021). Another criticism is that the establishment of FN and their autonomous adaptation through seed dispersal takes a long time and thus does not lead to rapid success.

51.7 Climate-smart forestry (CSF)

Climate-smart forestry (CSF) is not aiming to substitute Sustainable Forest Management (SFM), but seeks to optimize forest management in response to climate change (acc. to Bowditch et al., 2020).

CSF has three pillars:

- Removing CO2 to mitigate climate change

- Adapting forest management to enhance resilience, and

- Active forest management aiming to increase productivity and the provision of other ecosystem services.

Mitigation strategies comprise the afforestation on ‘new lands’, tree species choice with respect to growth rate and specific gravity of trees, the increase of rotation length and standing volume, more deadwood, the restoration of peatlands and the conservation of high carbon stocks in old forests and in forests on sensitive sites. Adaptation, however, focuses on the diversification of forests on stand and landscape level to enhance their resistance and resilience. Mitigation and adaptation are closely linked, i.e. without forests with adaptive capacity the function of forests as a carbon sink cannot be maintained on a long term.

FMS are a prerequisite for rational forest interventions and the fundamentals for active forest management. There is a global tendency of convergence from stand-based systems neglecting ecological processes to integrative approaches on landscape level, taking into account basic ecosystem processes. The more or less segregative part of the introduced systems is gaining importance, because protected (set aside) areas or wilderness areas are regarded as indispensable for biodiversity conservation (Jandl et al., 2019). Moreover, due to environmental change, the need for adaptive elements in FMS is strongly increasing. This has consequences for long-term planning horizons in forestry, as well as for monitoring and the necessity of flexible solutions and experimenting. Maybe a paradigm shift is emerging, that FMS and their type of intervention have to be more and more derived from ecosystem functioning and ecosystem integrity. For a more in-depth analysis of forest management systems, we recommend the following readings: Aquilé et al. (2021), Puettmann et al. (2015), Brang et al. (2014), Pommerening & Murphy (2004).

Aquilué N, Messier C, Martins KT, et al. 2021. A simple-to-use management approach to boost adaptive capacity of forests to global uncertainty. For Ecol Manage 481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118692

Ashton, M.S. & Kelty, M.J. 2018. The practice of silviculture. Applied forest ecology. Tenth Edition. Wiley. 779 pp.

Aszalós R, Thom D, Aakala T, et al. 2022. Natural disturbance regimes as a guide for sustainable forest management in Europe. Ecol Appl. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2596.

Bollmann, K, Krauss, D, Paillet, Y et al. 2020. A unifying framework for the conservation of biodiversity in multi-functional European forests. In Krumm et al. (Eds.) (2020). How to balance forestry and biodiversity conservation – A view across Europe. EFI and WSL, Birmensdorf. 27-45.

Borchers, J 2010. Segregation versus Multifunktionalität in der Forstwirtschaft. Forst und Holz 65. 44-49.

Bowditch, E, Santopuoli, G, Binder, F et al. 2020. What is Climate-Smart Forestry? A definition from a multinational collaborative process focused on mountain regions of Europe. Ecosystem Services 43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101113. Letzter Zugriff 03.01.2022.

Brang, P, Spathelf, P, Larsen JB et al. 2014. Suitability of close-to-nature silviculture for adapting temperate European forests to climate change. Forestry 87. 492-503.

de Koning, J, Lindner, M, Spathelf, P.et al. 2020. Integrated forest management and climate change adaptation in European forestry – A policy and practice review. INFORMAR Deliverable D2.3. European Forest Institute. 63 pp.

Diaci, J Rozenbergar, D Fidej, G, Nagel, T.A. 2017. Challenges for uneven-aged silviculture in restoration of post-disturbance forests in central Europe: A synthesis. Forests 8.

Gayer, K 1886 Der gemischte Wald, seine Begründung und Pflege, insbesondere durch Horst- und Gruppenwirtschaft. P. Parey.

Hahn, WA, Knoke, T 2010. Sustainable development and sustainable forestry: analogies, differences, and the role of flexibility. Eur J Forest Res 129, 787–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-010-0385-0.

Heyder, JC 1986. Waldbau im Wandel. JD Sauerländer’s Verlag.

Helliwell, DR 1997: Dauerwald. Forestry 70: 375-379.

Jandl, R, Spathelf, P, Bolte, A & Prescott, C 2019. Forest adaptation to climate change – is non-management an option? Annals of Forest Science, SI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0827-x.

Johann, E 2006. Historical development of nature-based forestry in Central Europe. In Nature-based forestry in Central Europe. Alternatives to industrial forestry and strict preservation. Diaci, J. (ed.). Proceedings, Univ. of Ljubljana, pp. 1–18.

Knoke, T, Ammer, C, Stimm, B and Mosandl, R 2008. Admixing broadleaved to coniferous tree species: a review on yield, ecological stability and economics. Eur. J. For. Res. 127, 89–101.

Krumm, F, Bollmann, K, Brang, P et al. 2020. Introduction: Context and solutions for integrating nature conservation into forest management: an overview. In Krumm et al. (Eds.) (2020). How to balance forestry and biodiversity conservation – A view across Europe. EFI and WSL, Birmensdorf. 10-26.

Larsen, JB, Angelstam P, Bauhus, J et al. 2022. Closer-to-Nature Forest Management. From Science to Policy 12. European Forest Institute.

Möller, A 1922. Der Dauerwaldgedanke. Sein Sinn und seine Bedeutung. Springer.

Münzer, L, Kazuhiko Masaka, K, Takisawa, Y, Hein, S, End, C, Sugita, H, Hoshino, D. 2023. Analysis of Selection-Cutting Silviculture with Thujopsis dolabrata—A Case Study from Japan Compared to German Plenter Forests. Forests 2023, 14(8), 1556; https://doi.org/10.3390/f14081556

Pommerening, A 2023. Continuous Cover Forestry. John Wiley & Sons. 416 p.

Pommerening, A & Murphy, T 2004. A review of the history, definitions and methods of continuous cover forestry with special attention to afforestation and restocking. Forestry 77, 27–44.

Puettmann, KJ, Wilson, SM, Baker, SC et al. 2015. Silvicultural alternatives to conventional even-aged forest management – what limits global adoption? For. Ecosyst. 2, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-015-0031-x

Schütz, J-P 1999. Close-to-nature silviculture: is this concept compatible with species richness? Forestry 72, 359–366.

Spathelf, P 1997. Seminatural silviculture in southwest Germany. Forestry Chronicle 73/6. 715–722.

Thom D, Taylor AR, Seidl R, et al. 2021. Forest structure, not climate, is the primary driver of functional diversity in northeastern North America. Sci Total Environ 762:143070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143070

Thomasius, H 1996. Geschichte, Anliegen und Wege des Waldumbaus in Sachsen. Schriftenreihe der Sächsischen Landesanstalt für Forsten 6. 11-52.

This Chapter is published on the EUROSILVICS platform, established as part of the EUROSILVICS Erasmus+ grant agreement No. 2022-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000086765.

Author affiliation:

|

Prof. Dr. Spathelf, Peter |

HNE Eberswalde, Schicklerstrasse 5, 16225 Eberswalde, Germany |