Chapter 12: Anatomy and morphology of trees – Download PDF

Authors: Ute Sass-Klaassen, Frank Sterck, Paul Copini, Monique Weemstra, Jan den Ouden

Author affiliations are given at the end of the chapter

Intended learning level: Basic / Advanced

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

| Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

| In this chapter the basic anatomy and morphology of trees is described. It covers the basic cell types, cell structures and tissue types of stem, leaves and roots, and the ways that trees become their general shape. |

NOTE: this part is a full draft, which in due time will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

12.2 Primary and secondary tree growth 3

12.2.1 Primary growth – via buds 3

12.2.2 Secondary growth via cambia 5

12.2.3 Adventitious meristems 8

12.3.1 Chemical composition of the cell wall 10

12.3.2 Structure of the cell wall 11

12.3.3 Cell types and tissues 12

12.3.4 Juvenile and mature wood 18

12.3.5 Sapwood and heartwood 19

12.3.6. Branch wood and root wood 21

12.3.8.Wound reactions in trees 26

12.3.9 Wood – transport tissue in the tree and valuable material for industry 28

12.4.1 General leaf structure 29

12.4.2 Chloroplasts and leaf senescence 31

12.5 Structure of the fine roots 33

12.7.1.2 Long shoots and short shoots 39

12.7.2 Quantitative tree models 40

12.7.3 Mechanical design of trees 41

12 Anatomy and morphology of trees

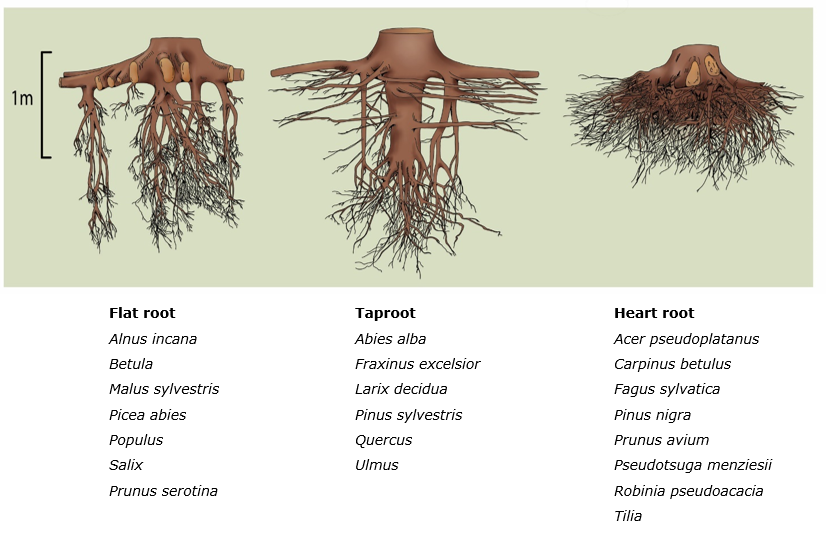

Trees are long-lived organisms that use various strategies to cope with changes in their environment throughout their lifetimes. An adult tree forms a complex aboveground structure, consisting of a central trunk and branches that end in small twigs carrying leaves for assimilate production and flowers and cones for reproduction. Below-ground, the root system branches out, starting with coarse roots that anchor the tree and ending with the fine roots that – often in mycorrhizal association with fungi – explore the soil and acquire water and nutrients. Each tree species has its own characteristic branching and rooting pattern, which can vary with tree age and specific environmental conditions. Despite this tremendous diversity of forms, the fundamental rules for tree growth are the same for all trees. In this chapter a distinction in characteristics is made between broadleaved trees and conifers. This refers to trees belonging to the clade of Angiosperms (flowering plants with seeds enclosed by fruits) and the clade of Gymnosperms (plants with naked seeds), respectively. Conifers not only include trees with needle-shaped leaves, such as spruce and pine, but also those with scale-like leaves, such as Western red cedar (Thuja plicata) and Lawson’s cypress (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana).

12.2 Primary and secondary tree growth

The best way to understand tree growth is to envision growth as the accumulation of similar “building blocks” resulting from meristem activity. Meristems are specialised cell tissues that are composed of living, dividing cells that can develop into various specialised tissue types and structures. The tree has two major types of meristems: the apical and lateral meristems. The apical meristems are located in the tips of growing shoots and roots and are responsible for primary (length) growth. Lateral meristems, such as the vascular cambium, form a circular layer around the outer parts of the branches, trunk, and roots, and produce wood and bark tissues. The growth from the vascular cambium leads to an increase in thickness or girth and is referred to as secondary growth.

12.2.1 Primary growth – via buds

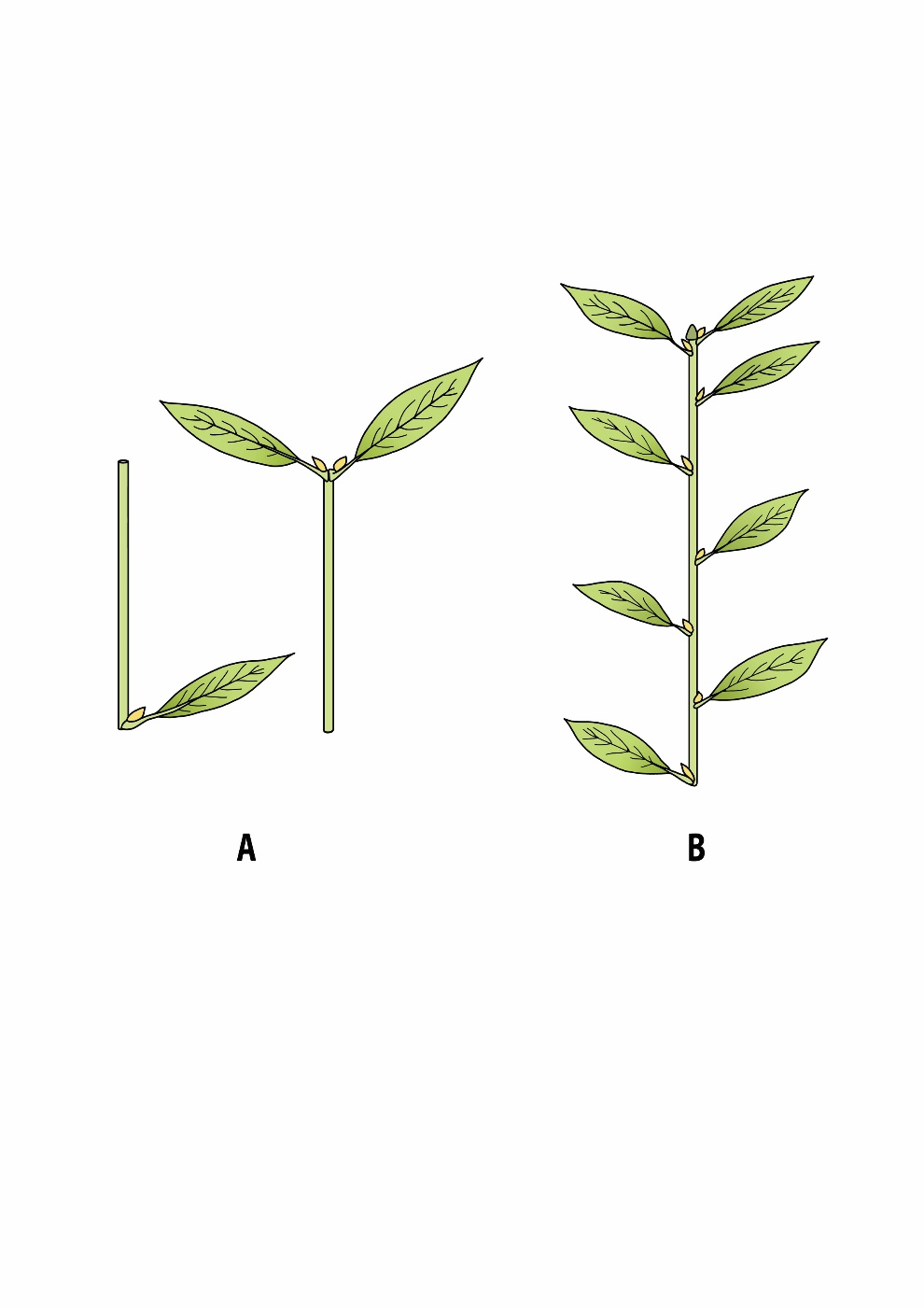

The fundamental unit or building block of primary growth is the metamer (synonym: phytomer). It consists of an internode and a node, a leaf and a bud (Figure 12-1). Metamers are produced by meristems in the terminal bud (apical bud or apex) or the lateral bud (axillary bud or axil). Typically, these meristems are protected by bud scales and produce one or multiple metamers per year. When the buds start to flush, the cells in these metamers absorb moisture, elongate, and form a new shoot (Figure 12-1). In most coniferous tree species, the annual shoot is preformed within the bud, meaning that its length is determined during bud formation at the end of the previous growing season, and elongates all at once after budbreak. In most broadleaved tree species, however, the meristem continues to produce new metamers after bud break, until an internal or external stimulus induces meristem dormancy and the formation of a new terminal bud.

Figure 12-1: A: Two visualizations of a metamer, the basic building block for longitudinal tree growth. The woody segment (cylindrical) consists of an internode and a node. The leaf is attached to the node, and in the leaf axil, a lateral bud (axillary bud) is formed; left: species with alternate leaves, right: species with opposite leaves (with two axillary buds per metamer). B: Shoots with alternate leaves composed of several metamers and ending in an apical bud.

As a rule, each shoot typically consists of a series of metamers ending in a terminal bud, with one or multiple leaves and lateral buds at each node. Occasionally, the leaves may only be rudimentarily developed and will quickly shed, making the modular structure of the shoot difficult to observe. Apical buds can form long branch axes by producing multiple shoots in succession. Trees in temperate regions usually produce one, but sometimes also multiple, shoots each year. When a lateral bud sprouts, a new branch axis is formed, and the tree branches out. In this way, the apical and lateral buds determine the development of the hierarchical structure (formation of branch complexes, shoots, and metamers) and thus the size and architecture of a tree.

Not all lateral buds sprout in the same year they were formed. Some buds remain dormant and grow along with the wood in the subsequent years (Meier et al., 2012). Such dormant buds (latent or epicormic buds) are located just underneath the bark and remain connected to the central pith by a row of parenchyma cells forming the bud trace. These dormant buds can sprout decades later under the influence of an external or internal stimulus. This stimulus can be, for example, increased temperature due to direct exposure to sunlight, or altered hormonal concentration gradients in the tree to restore the leaf area (photosynthetic capacity) when the plant is damaged by breakage, cutting or browsing. Once dormant buds develop into new shoots and break through the bark, new clusters of branches, the epicormic shoots (or water sprouts), form along the trunk. With these dormant buds, trees always maintain a reserve supply of growth points to compensate for the loss of branches and twigs or to quickly respond to changes in light conditions.

12.2.2 Secondary growth via cambia

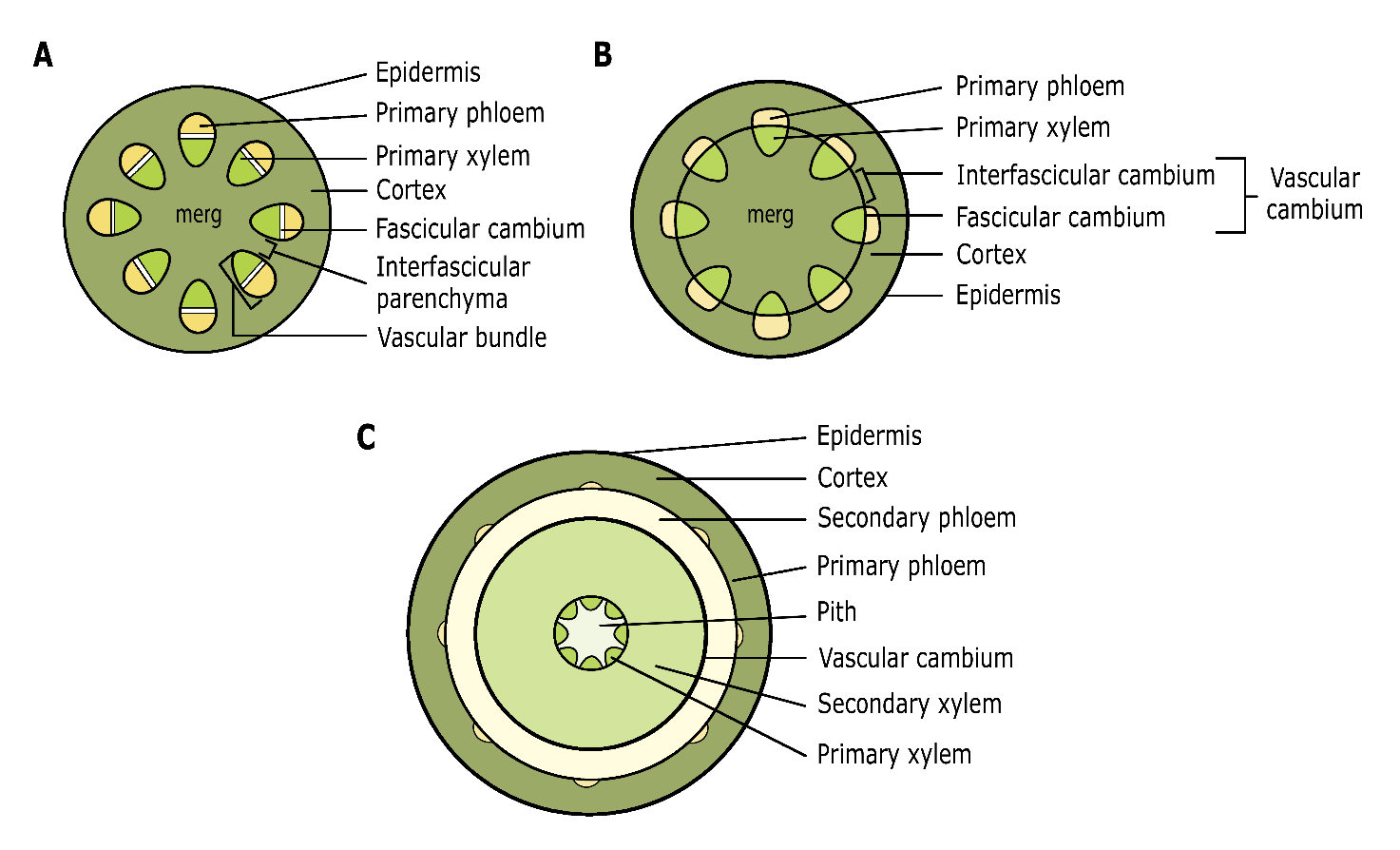

When apical and lateral buds start to develop into a shoot, first the primary xylem and phloem and the fascicular cambium – located in the vascular bundles – are formed by the procambium; the protective epidermis is formed by the protoderm (Figure 12-2). Vascular bundles, arranged in the cortex around the central pith, facilitate the transport of water and sugars in the primary xylem and phloem, respectively. Both the cortex and the pith consist of parenchyma cells. Parenchyma cells are living cells with thin, weakly lignified cell walls and include all necessary cell organelles of a plant cell. Parenchyma cells in the cortex also include chloroplasts (chlorophyll-bearing organelles), which give the young shoots their green colour. During the first growing season, the fascicular cambium merges with the interfascicular cambium that is formed when parenchyma cells, located between vascular bundles, dedifferentiate and become meristematic. The resulting cambium ring (vascular cambium) then initiates secondary growth (lateral growth or radial growth), forming xylem (or wood) towards the inside, and phloem (or bark) towards the outside (Figures 12-2, 12-3).

Figure 12-2: Schematic cross-section of the primary shoot developing from the apical meristems. Initially, a shoot is formed with primary xylem and phloem present in separate vascular bundles (A). Later, parenchyma tissue differentiates into interfascicular cambium, together with the fascicular cambium in the vascular bundles forming a closed cambium ring; (B) the cambium undergoes cell division to facilitate secondary growth, with xylem tissue formed towards the interior and phloem towards the exterior. This ultimately results in the basic structure of a woody stem (C). See text for explanations of different tissue types. Adapted from T.L. Rost, University of California, Davis.

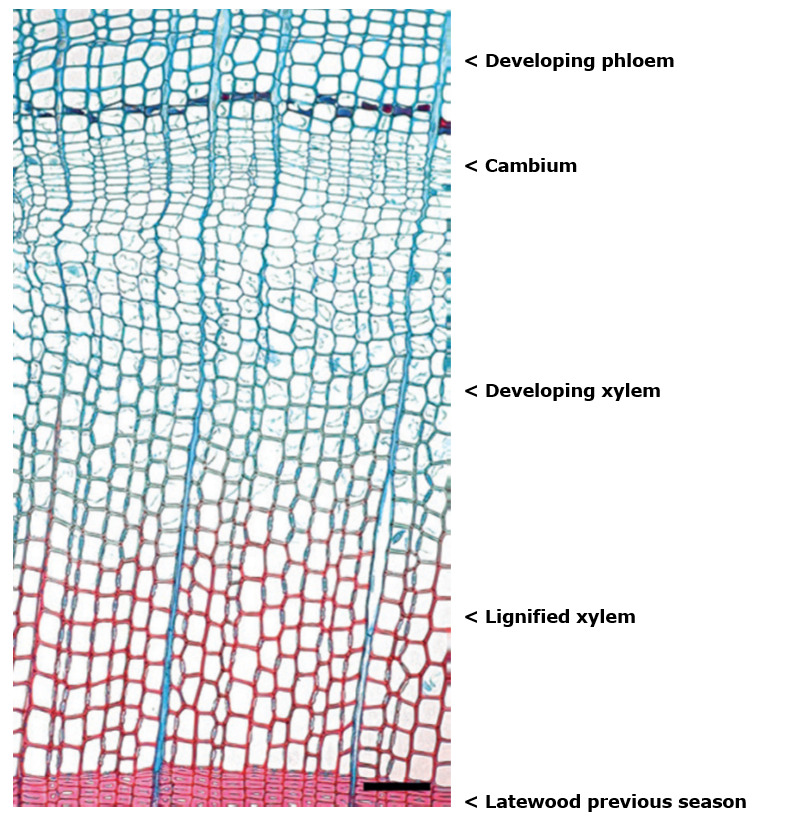

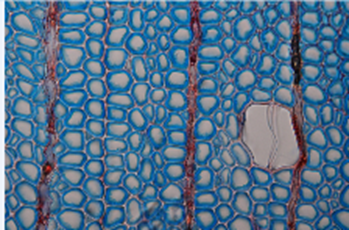

Figure 12-3: Wood formation in a conifer tree (Norway spruce). Cambium produces xylem to the inside (bottom) and phloem to the outside (top). The image reflects the situation in June, in the middle of the growing season, when the cambium is very active. Non-lignified tissue is stained blue and lignified tissue is stained red. Fully lignified tracheids are ready to function; parenchyma cells in rays stay weakly or non-lignified. Scale bar = 100 μm. Picture by J. Gričar, in Sass-Klaassen (2015)

During the formation of phloem, the epidermis is gradually pushed outward, dries out, cracks, and falls off. It is replaced by new tissue, the periderm, which is formed by the cork cambium (phellogen) (Serra et al., 2022; Angyalossy et al., 2016). The cork cambium (Figure 12-4) is, like the interfascicular cambium, created from parenchyma cells in the bark that become meristematic. In broadleaved trees, it produces parenchyma or secondary cortex cells inward, called the phelloderm, and usually a wide layer of cork cells outward, known as the phellem. The periderm of coniferous trees has a more complex structure. Their phellem consists of cork cells characterised by a thick secondary cell wall containing suberin; in some pine species the thick-walled cells develop into heavily lignified stone cells.

In some cases, the initially formed periderm remains intact for a long time or even throughout the life of the tree, as is the case of beech or hornbeam. However, usually it undergoes the same fate as the epidermis and is ripped apart due to the increasing stem girth. Underneath, a new periderm is then formed in the living inner bark. The outer bark then contains cork and old, dead phloem. The successive periderms, along with the outer bark, constitute a strong protective tissue. The cork cells have a hexagonal shape, resembling a honeycomb structure. These cells are dead, filled with air, tightly packed together, and highly elastic. They protect the phloem in the inner bark against water loss and solar radiation, and against mechanical damage due to grazing, diseases, fire, or falling trees and branches.

Figure 12-4: Basic structure of the xylem and phloem of a broadleaved species. In addition to the vascular cambium, which produces xylem and phloem, a second ring of dividing tissue is present: the phellogen or cork cambium. After D’Arcy et al. (2001).

The phloem of broadleaved species consists of sieve tubes, accompanied by metabolically active companion cells (Figure 12-4) while gymnosperms hold sieve cells and ‘Strasburger cells’ as counterparts. Sieve tubes and sieve cells are responsible for long-distance transport of sugars between leaves and all other parts of the plant. Additionally, axial and radial phloem parenchyma cells facilitate storage and radial transport of sugars. Bark fibers and occasionally sclereids (stone cells) provide mechanical support.

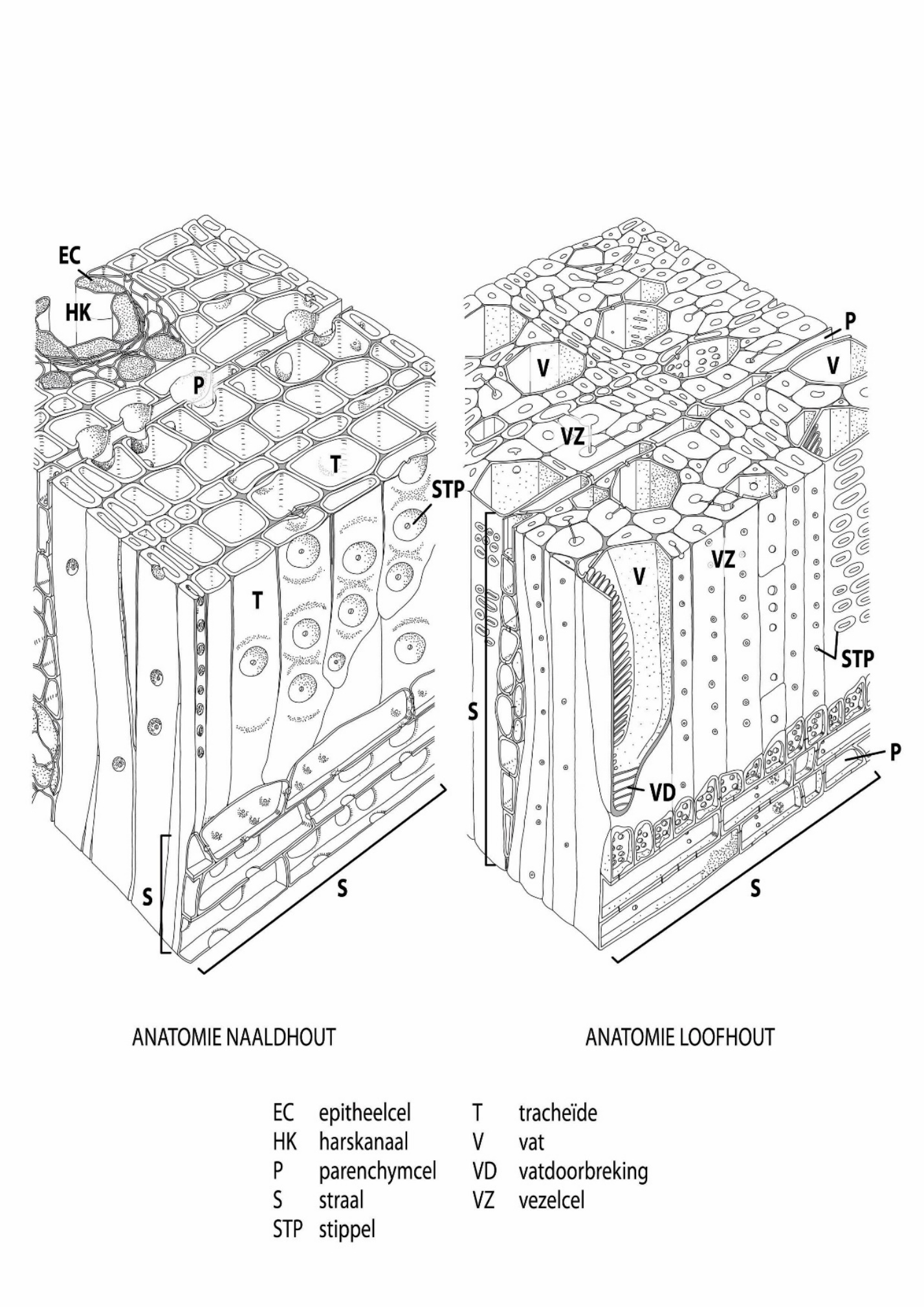

The structure of the xylem is notably different between broadleaved trees and conifer trees (see 12-3). The wood of conifers mainly consists of tracheids, responsible for the transportation of water and nutrients from the roots to the rest of the plant and the provision of mechanical strength to the wood. In the more advanced broadleaved trees, the transport of water and nutrients takes place in the vessels of the wood, while the fibers are responsible for the strength of the wood. Finally, the pith, consisting of parenchyma cells contributes to the storage of water and sugars (starch) produced in the leaves during the initial years.

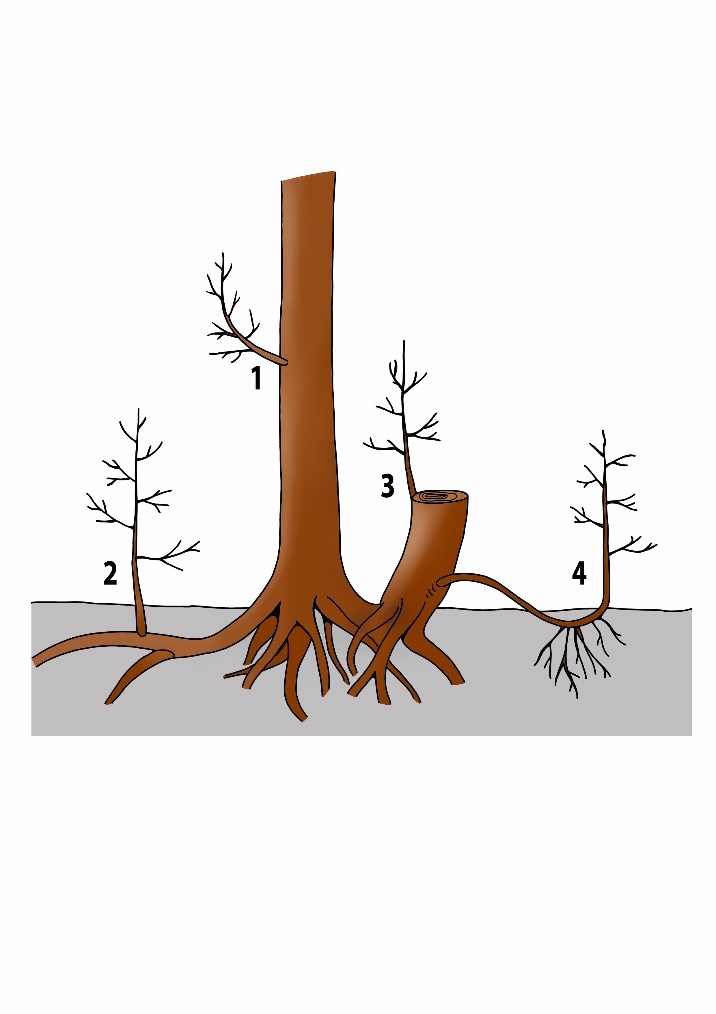

Cambium cells can be considered as stem cells. They can differentiate into any cell type (vessel element, parenchyma cell, fibre etc.). Normally, the cambium produces cells that become part of the xylem or phloem, but due to an internal or external stimulus (such as injury or sudden environmental change), the cambium can also produce new shoot or root meristems. However, such new shoots or roots may also arise from other tissue types, such as parenchyma cells, that re-differentiate into cells that then start developing into shoots or roots. This gives rise to new adventitious (from the Latin adventus: arrival or coming), structures in places along the plant where they are normally not expected to be formed. In this way entirely new shoot complexes, and even new trees can develop (Figure 12-5). These can occur as epicormic branches or water sprouts where branches develop on the trunk, stump sprouts that arise from the stump after tree felling, root sprouts or suckers where new shoots emerge from the root system, or the formation of roots on a buried branch, resulting in layering (see Koop, 1987; den Ouden et al., 2007). In coppicing (see chapter 46), both sleeping buds and adventitious buds play a role in resprouting, depending on the tree species and its specific regenerative capabilities. Some species, like oak and ash, may rely more on dormant buds (sleeping buds) for regrowth, while others, like beech, rely primarily on resprouting from adventitious buds.

Figure 12-5: Different ways in which adventitious meristems and dormant buds can form new shoots and roots.

1: epicormic shoot or water sprout,

2: root spout or sucker,

3: stump sprout,

4: layering.

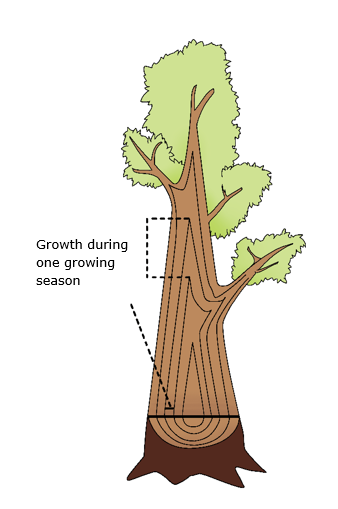

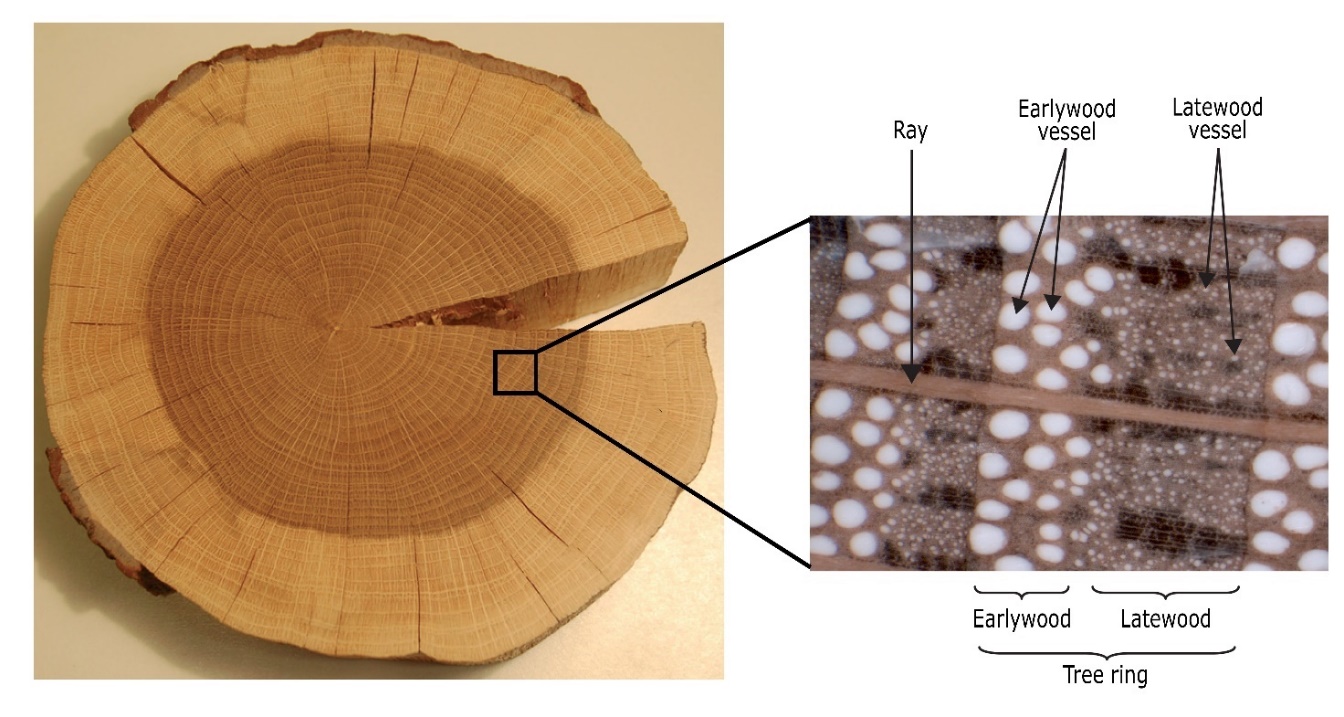

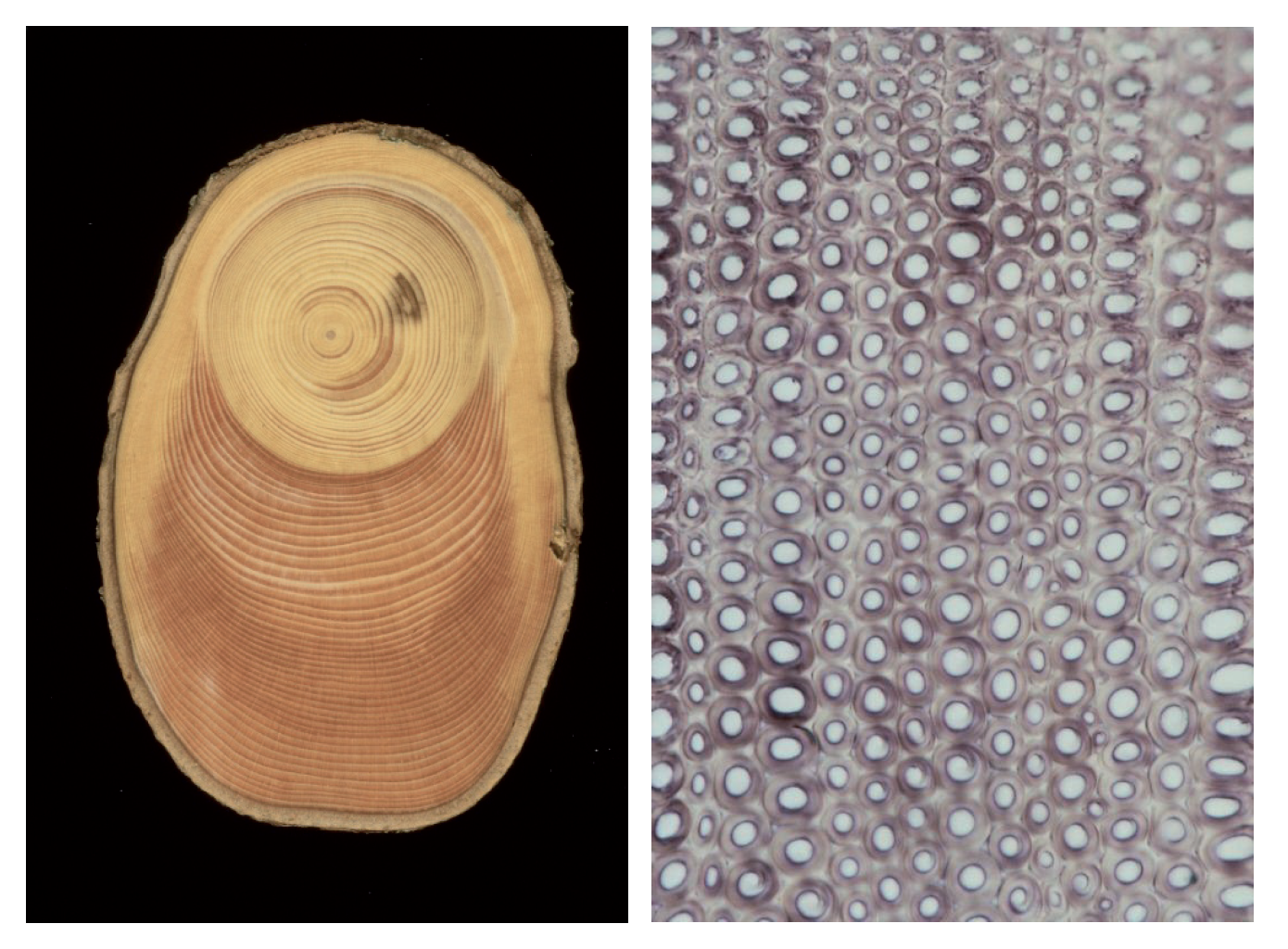

Although wood (xylem) holds the same function in the estimated 138.500 woody species of (Fazan et al., 2020), including the 73.000 tree species on earth (Gatti et al., 2022), the stem morphology as well as the anatomy and chemical composition of the wood varies tremendously between species. This variety can serve to identify species based on their wood-anatomical characteristic (Wheeler, 2011; InsideWood webpage) and defines specific wood properties. The wood, or xylem, is responsible for the transport of water from the roots to the leaves, storage of water and assimilates, and reinforcement of the trunk, branches, and roots. In seasonal climates, during the growing season, the vascular cambium forms a new layer of wood around the entire tree each year, from the highest shoot to the lowest root (Figure 12-3, 12-6). This allows the tree to increase in size and continuously produce new physiologically active tissue for transport, storage, and stability.

The amount of wood formed each year, its distribution along the tree, and the structure of the wood tissue depend on different external factors, such as weather conditions and competition with other trees. These factors determine the availability of resources such as light, water and temperature that influence the photosynthetic activity of a tree and hence the production of assimilates needed for all physiological processes. Mechanical stress induced by wind or unstable soils affects the distribution of wood around and along the tree trunk, leading to the formation of reaction wood (see 12.3.7). Internal factors such as the age and vitality of the tree also play a role in the amount and characteristics of the wood that is formed.

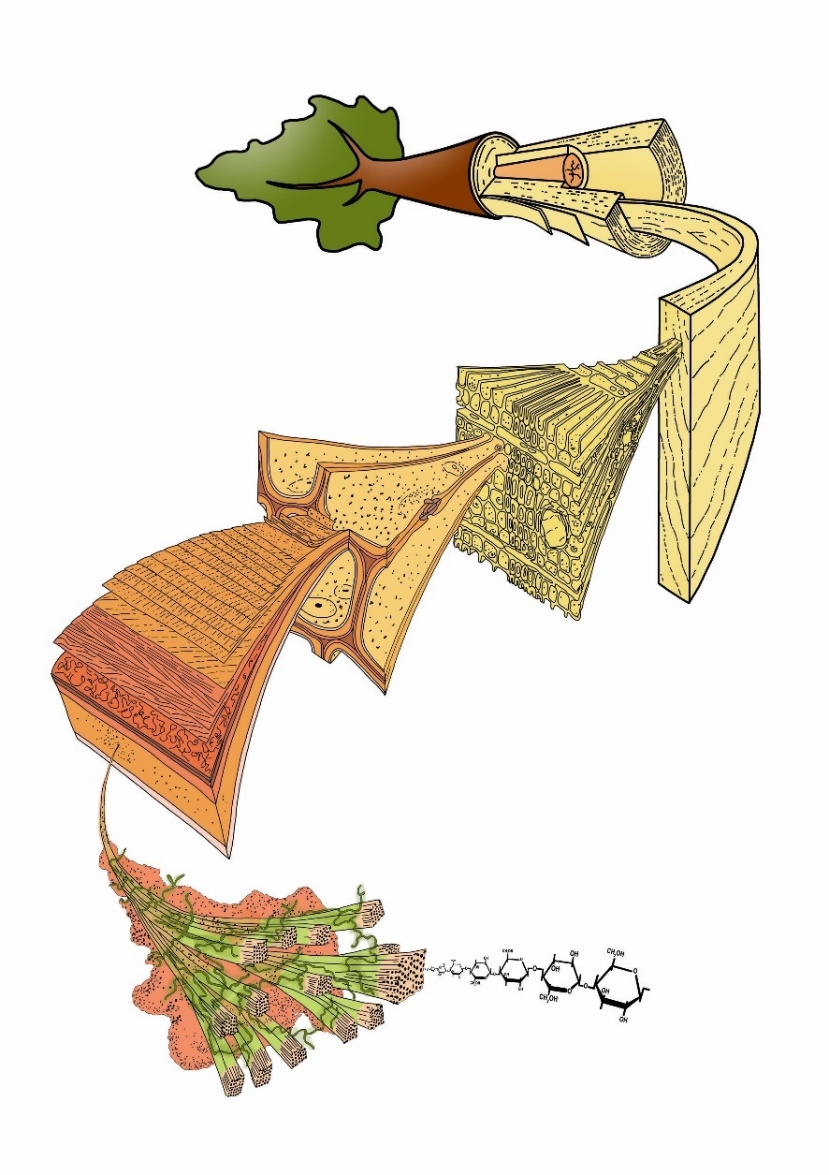

Wood has excellent strength properties: it can withstand high tensile as well as compression forces, enabling trees to grow to large dimensions and making wood a valued, renewable construction material. These properties are related to the specific wood structure and stem morphology, ranging from chemical composition and ultrastructure of the cell wall to changes of the wood matrix with increasing tree age (Figure 12-7).

Figure 12-6: Formation of wood in the tree leads to growth in length and thickness: each year a new layer of wood is formed by the cambium around the entire tree.

12.3.1 Chemical composition of the cell wall

The woody cell wall mainly consists of cellulose (approximately 40%), lignin (approximately 20-35%) and hemicellulose (approximately 15-35%). Especially heartwood (see 12.3.5) can also include various extractive compounds (up to approximately 10%). Conifer species contain relatively more and a different type of lignin, and less hemicellulose, than broadleaved tree species. There is also variation in the chemical composition of wood within the tree, mainly influenced by the proportion of juvenile wood (see 12.3.4) and reaction wood (see 12.3.7).

Figure 12-7: The structure of wood in a tree at different levels, ranging from the basic constituent cellulose, that is arranged in microfibrils which form a composite with hemicellulose and lignin in the multi-layered cell wall which constitutes the dead cells, but also forms an essential part of living cells. The many dead and few living cells (radial and sometimes axial parenchyma) constitute the xylem. The xylem is organised in growth rings reflecting its way of formation through time. In case of tree species growing under a seasonal climate with one pronounced growing season and one dormant season, annual tree rings are formed. With aging of the tree and increasing tree-ring number xylem structure slightly changes; moreover, secondary changes of the xylem such as heartwood formation can occur in some species making that the wood structure along and across the stem is not homogeneous. Adapted from M. Harrington, University of Canterbury.

Cellulose consists of elongated chains of glucose molecules. These chains are connected to each other to form long axially orientated strands known as microfibrils that provide the tensile strength to wood (Figure 12-7). Lignin is a complex, highly branched macromolecule composed of aromatic rings, providing compression strength and resistance against fungal attack. Hemicellulose consists of highly branched chains of glucose molecules that stabilizes and further strengthens the cell wall. These three basic chemical components are interconnected in the cell wall and can be seen as a composite, such as reinforced concrete: cellulose acts as the reinforcement (steel cables), lignin as aggregate, with hemicellulose as binding element between the two (cement). Additionally, heartwood (see 12.3.5) contains a wide range of aromatic extractives, such as tannins, resins, gum-like substances, and oily compounds. In tree species that form heartwood these substances contribute to the wood’s resistance against biological decay. The number of extractives and their toxicity varies greatly between tree species and is often higher in tropical species than in trees from the temperate zone. Teak (Tectona grandis), for example, is known for its durable wood, primarily due to the oily extractives impregnating the cell walls of its heartwood. In the temperate zone, black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) is among the species with the most durable heartwood. Its high tannin content makes the wood highly resistant to fungal and insect attacks. The high durability of Western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is caused by the toxic extractive β-Thujaplicin.

12.3.2 Structure of the cell wall

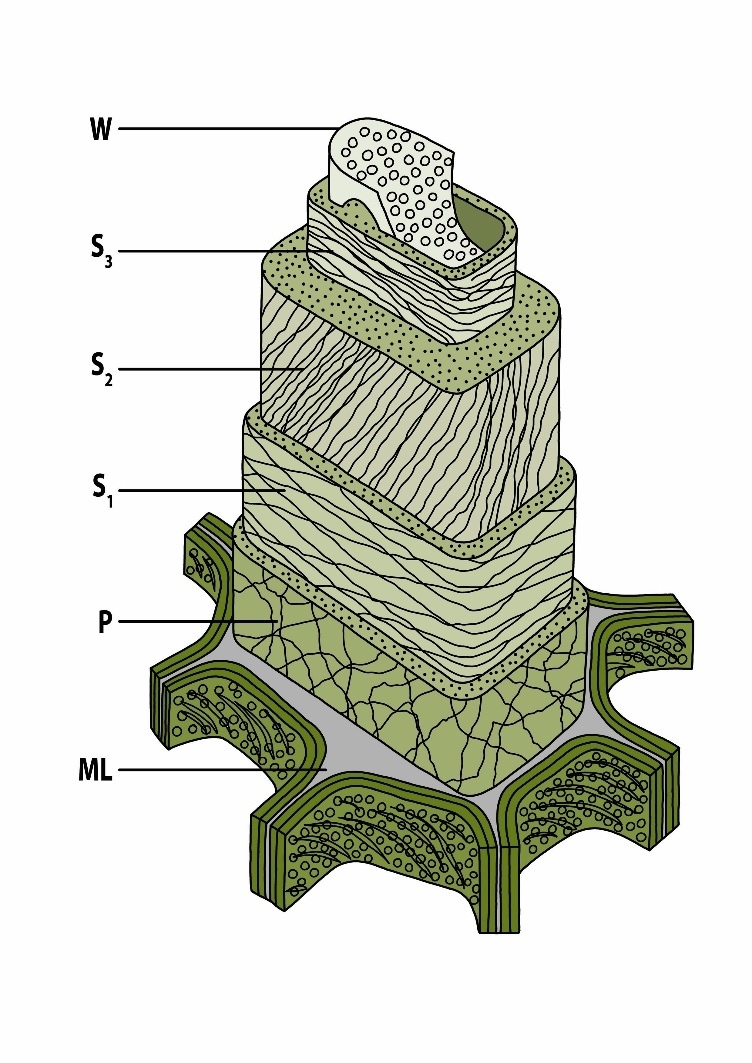

The cell wall is composed of multiple layers that vary in thickness and chemical composition (Figure 12-8). The thin middle lamella is synthesised and shared by neighbouring cells. It has a high content of lignin and pectin, a polysaccharide that acts as a cementing material and binds the walls of the cells together. On the middle lamella lies the primary wall, which is formed by, and belongs to, each cell. The primary wall contains roughly equal amounts of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, with the cellulose microfibrils intersecting each other in a criss-crossed manner. The secondary wall is the most important and thickest part of the cell wall, essentially forming most of the wood and determining its properties. The structure of the secondary wall varies between cell types and tree species but always consists of multiple layers: a thin layer (S1) followed by a thick layer (S2), in some species followed by another thin layer (S3). On the S2 or S3, there may even be a tertiary wall and/or a warty layer present. The warty layer consists of small local thickenings that occur as the final step in the formation of the cell wall.

The secondary wall contains a relatively high amount of cellulose. The microfibrils in the S1 and S3 are more horizontally orientated (shallow angle), while they are almost vertically oriented (steep angle) in the S2. The layering and alternating orientation of the microfibrils in the cell wall are like the structure of fiberglass or plywood, where multiple layers with different grain orientations are combined to ensure optimal mechanical strength and dimensional stability. Related to their functions, cell types differ in their cell-wall structure. The living parenchyma cells usually have a primary wall and either lack a secondary wall or have a thin, poorly or non-lignified secondary wall layer (Figure 12-3).

Tracheids, fibres and also vessels need strong, multilayered and lignified cell walls to fulfil their function in either mechanical support or water transport under high pressure (see chapter 13). This is provided by the massive S2 layer, which contains a large amount of lignin in absolute terms as well as cellulose orientated in a steep microfibril angle, enable tracheid and fibre cells to withstand large compression and tensile forces.

Figure 12-8: Simplified multi-layered ultrastructure of a woody cell wall (tracheid): W = warty layer, S1-S3 = secondary cell walls, P = primary wall, ML = middle lamella. Adapted from Côté (1967).

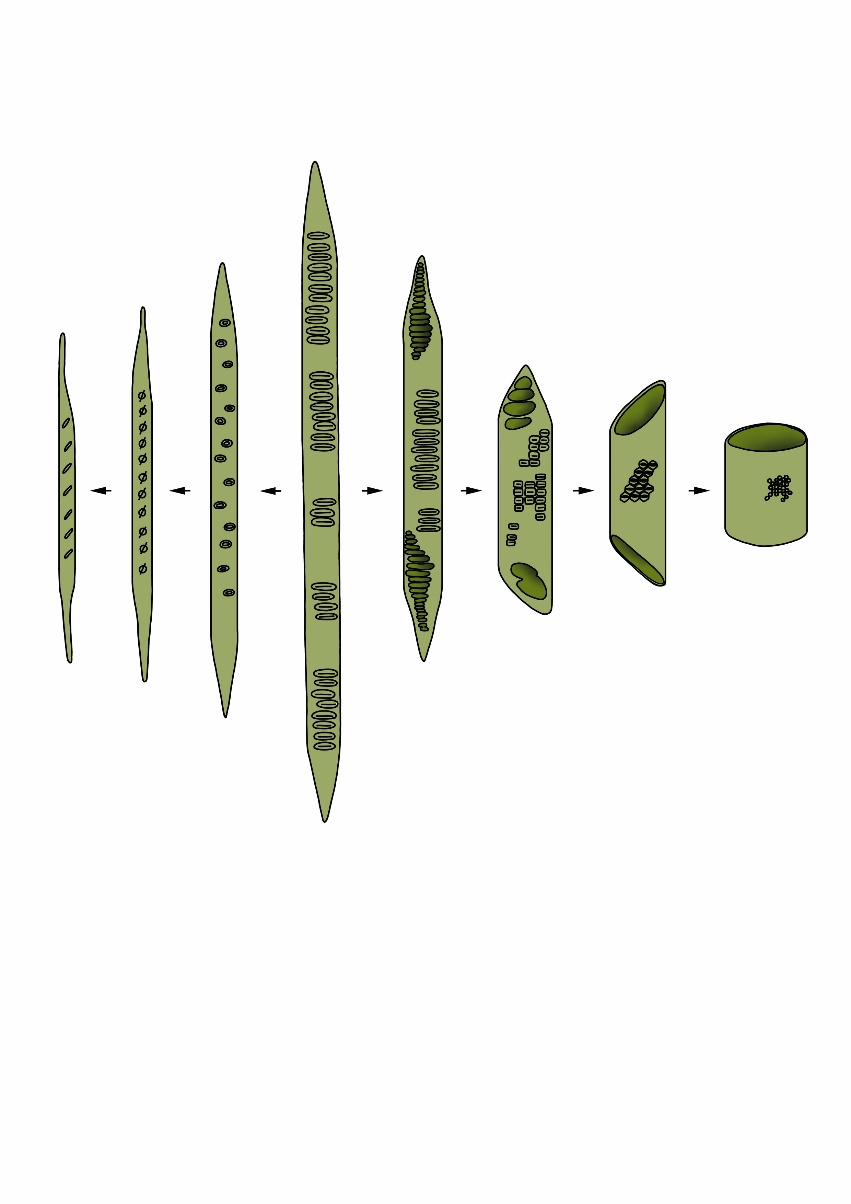

Evolution of woody plants

The evolutionary development of woody plants has been shaped to ensure efficient water transport. About 400 million years ago during the Carboniferous period, plants evolved that could produce lignin and tracheids, giving rise to wood cells as we still find in coniferous trees (gymnosperms) today. This enabled plants to grow much taller than before, providing a significant competitive advantage over the lower existing vegetation of tree ferns, giant horsetails, etc. The phylogenetically younger broadleaved tree species (angiosperms) developed less than 100 million years ago during the Cretaceous period (Nathan et al., 2018). In broadleaved tree species, the development of more specialized cells caused a divergence in cell types specialized for water transport or structural support. Vessel elements with larger cell lumen ensure more efficient water transport than the tracheids of conifer species. Long fibres with thicker cell walls provide mechanical strength of the wood (Figure 12-9). The fact that coniferous and broadleaved species coexist in various habitats, and that the gymnosperm Sequoia sempervirens (USA) and angiosperm Eucalyptus regnans (Australia) both reach heights over 110 m, confirms the success of both wood structure types that provide the same means to an end.

Figure 12-9: Overview of different cell types in softwood and hardwood tree species. Softwood is composed of tracheids (longest central cell). In broadleaved trees, these primary tracheids evolved into fibre cells for mechanical strength (left) or vessel elements for water and nutrient transport (right). Adapted from Bailey and Tupper (1918).

Wood anatomy of conifer and broadleaved species

The anatomy of wood strongly differs between gymnosperms and angiosperms. The presence or absence and the proportion of different cell- and tissue types, their spatial distribution and morphology characterise a plant family, a genus, or a species.

Almost all cells and tissues in wood are axially oriented, meaning that they vertically align along the stem. This relates to the main function of wood, the vertical transport of water from the roots to the leaves. Only the rays cells are oriented radially, running in centrifugal direction from the centre towards the cambium (Figure 12-10). Rays that are initiated in the very beginning of the shoot are called medullary rays; they stretch from the pith to the cambium. Additional rays are initiated later by the cambium to support the increasing amount of wood tissue that is formed due to the increase of the tree circumference. Rays are composed of living parenchyma cells. The radial width of the rays can strongly differ. In some species rays are only one cell wide, such as poplar, while in species such as oak and beech the rays are more than 10 cells wide.

In some conifer species resin canals are imbedded in rays forming a defence network with the axially running resin canals. Another phenomenon in many conifer species, such as pine, are so-called heterocellular rays, indicating that the ray parenchyma is sandwiched by a row of also horizontally orientated tracheids. Broadleaved species also hold two types of rays: homogenous rays consisting of only lying (procumbent) parenchyma cells or heterogenous rays characterised by outer rows of upright parenchyma cells. This difference in ray structure is an important feature to distinguish between two species that are very similar in wood anatomy: poplar (homogenous) and willow (heterogenous).

In all species the rays – in some species supported by axial parenchyma cells – form the “physiological motor” of the tree. They are imbedded in a matrix of dead cells (vessels, tracheids and fibres) that either transport water or provide stiffness. Rays facilitate the transport of assimilates and water between the bark, cambium, and wood, store sugars, and control important physiological processes such as frost protection of cells against ice formation during winter, re-activation of the water transport in spring, protection of the wood matrix after wounding through compartmentalisation (see 12.3.8) and conversion of living sapwood into dead heartwood (see 12.3.5). Additionally, they contribute to the mechanical stability (radial tensile strength) of the wood.

Figure 12-10: Cross-section of an oak stem. The xylem can be further divided into heartwood (dark-coloured) and sapwood (light-coloured: see 12.3.5). The annual growth rings are clearly visible due to the ring-porous wood structure; the wood matrix is formed by vertically orientated vessel and fibres (oaks also hold tracheids supporting water transport). Rays, consisting of living parenchyma cells, are running in radial direction and support and protect the dead tissue. Photo: Leo Goudzwaard

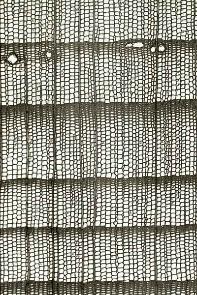

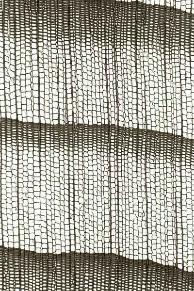

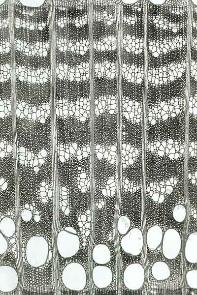

Wood anatomy of conifers

Conifer species are much simpler in wood structure than broadleaved species (Figures 12-11, 12-12; Table 12-1). Their wood mainly consists of two types of cells: dead tracheid cells and living ray parenchyma cells. Tracheids are axially oriented cells, approximately 2-6 mm in length and around 20 μm in diameter. The dead tracheids have two functions in conifer wood: water transport and mechanical support. Pits form the connection between tracheids, but also between tracheids and ray parenchyma cells. They resemble valves that are mainly open, allowing a relatively free flow of water from cell to cell up the tree from roots to the canopy. However, if there is a water transport obstruction, for example as a consequence of mechanical injury or cell embolism due to high tension forces during drought, the pit then closes which isolates the affected cell from the rest of the undamaged water-conducting tissue (Tyree & Sperry, 1988).

Parenchyma cells in coniferous wood are almost exclusively found in rays and sporadically as axial parenchyma embedded among the tracheids (e.g. in juniper). In the physiologically active sapwood (see 12.3.5), parenchyma cells are the only living cells. They are connected to each other and to the tracheids by different types of pits, and serve as radial transport pathways and for storage of water and assimilates.

Many conifer species (such as spruce, pine, larch, and Douglas fir, but not silver fir) have resin canals, also known as resin ducts. These are axial or radial (in the rays) tubes surrounded by living epithelial cells (specialized parenchyma cells) that produce resin. Axial and radial resin canals together form a network throughout the wood. In case of injuries, for example caused by branch breakage or insect damage, resin helps to seal the wound.

EC – epithelial cell T – tracheid

HK – resin canal V – vessel

P – parenchyma VD – vessel connection

S – ray VZ – fibre

STP – pit

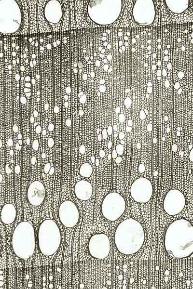

Figure 12-11: The general structure of xylem in confers (left) and broadleaved species (right). Adapted from Panshin & de Zeeuw (1980).

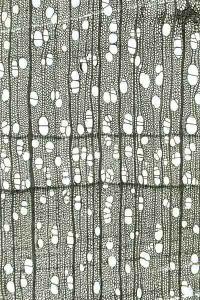

Wood anatomy of broadleaved species

Broadleaved species are more complex in wood structure compared to conifer species, with a clear division of tasks among the different cell types (Figures 12-11, 12-12; Table 12-1). The vessels are responsible for water transport. They consist of stacked vessel elements, sometimes with very large cell lumen, up to more than 300 μm in diameter in oak species, ranging in length from a few centimetres to over ten metres (as found in oak). Vessels form an axially oriented network throughout the entire tree. Ladder-like, sieve-like, or simple perforations can be found at the top and bottom of individual vessel elements, and there are different types of pits in the cell walls for connections within and between cell types.

A distinction can be made between ring-porous and diffuse-porous hardwood species, based on the size and distribution of vessels within a tree ring, (Figure 12-12). Ring-porous species (such as oak, common ash, European white elm, black locust, and sweet chestnut) start wood formation in spring by forming a tangential ring of very large vessels of often more than 300 μm in diameter. This so-called earlywood can be clearly distinguished from the latewood that is formed in summer and contains much smaller vessels ranging in size between approximately 20-30 μm (Figure 12-10). Diffuse-porous species (such as beech, birch, maple, alder, willow, and poplar) generally form smaller vessels (approximately 50-100 μm in diameter) with less variation in size across the tree ring. In most diffuse-porous species the largest vessels are often formed in the beginning of the growing season and mark the transition from one tree ring to the next. In addition to large vessels, many species (such as pedunculate oak, sweet chestnut, and eucalyptus) also possess narrower tracheids, often connected to vessels for water transport and storage in the xylem.

The fibres, elongated dead cells with thick cell walls and small cell lumen, provide mechanical stability. Some tropical hardwood species have living fibres, which can support or substitute parenchyma cells in their function of assimilate storage and distribution. As in conifers, the radially (rays) and axially oriented living parenchyma cells in broadleaved species are mainly responsible for the transport and storage of assimilates; they can, however, also serve for slow radial water transport. The living parenchyma cells are key for all physiological processes in the tree including the reaction to mechanical injury, e.g. caused by breaking-off of branches, damage of roots, or attacks by insects (see 12.3.8).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 12-12: Wood structure of a selection of conifer and broadleaved species; growth occurs from left to right. Top row: conifer species: Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii, left) and Silver Fir (Abies alba, right). Middle row: ring-porous broadleaved species: European White Elm (Ulmus laevis, left) and Sweet chestnut (Castanaea sativa, right). Bottom row: diffuse porous broadleaved species: beech (Fagus sylvatica, left), and Silver Birch (Betula pendula, right); black bar=1mm; Photos by Fritz Schweingruber.

Figure 12-13: Formation of tyloses by outgrowth of adjacent parenchyma cells into a vessel of sweet chestnut (left: magnified 400 times), and vessel occlusion by tyloses in a pedunculate oak (right: magnified 32 times). Photos by Fritz Schweingruber.

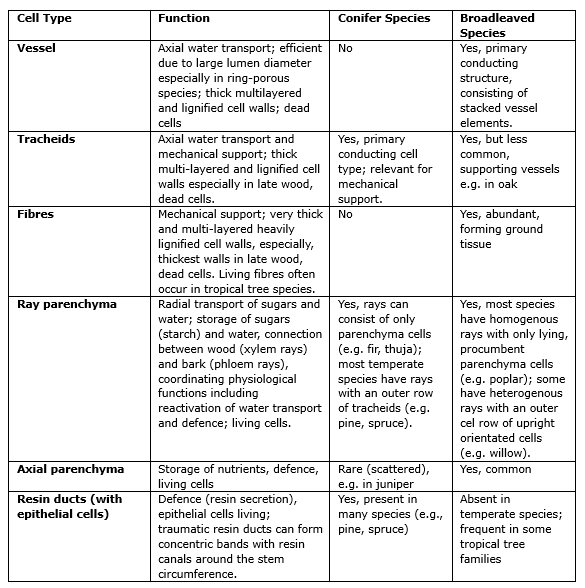

Table 12-1. Main wood cell types and associated functions in conifers and broadleaved species

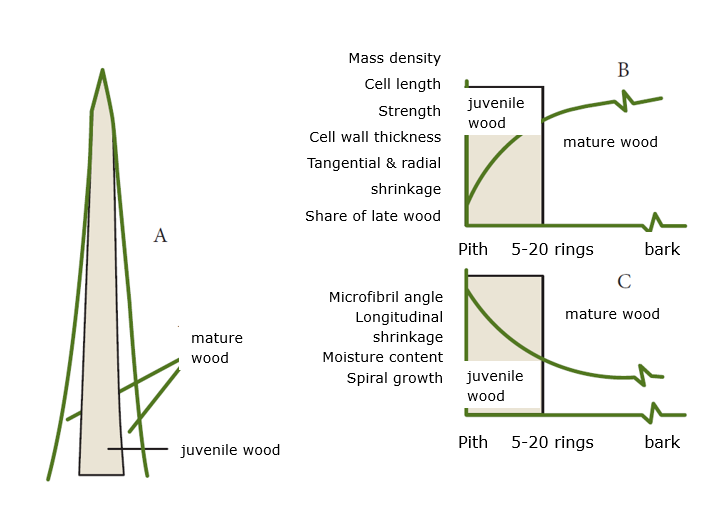

12.3.4 Juvenile and mature wood

In the first 20 to 30 years of growth, the young tree – or more precisely: the young cambium – forms juvenile wood. In the older tree, the juvenile wood is located in the crown and upper stem section and can be found as a cylinder extending through the central stem section around the pith (Figure 12-14). As the tree ages, mature wood is formed, starting in the lower stem section. Juvenile wood has shorter tracheids or fibres with thinner cell walls (lower wood density) and the microfibrils in the S2 of the cell wall run less steeply (lower micro-fibril angle) than in mature wood. This results in weaker strength properties of juvenile wood and greater shrinkage compared to mature wood. Stems from plantations with short rotation periods consist mainly of juvenile wood, and as a result, have lower wood quality than stems from old trees containing more mature wood.

Figure 12-14: Distribution of juvenile and mature wood in the tree (a) and its effect on physical and mechanical properties of both wood types, plotted against the number of growth rings from the pith, with properties increasing (b) or decreasing (c) as the tree ring is farther from the pith. Adapted from Kretschman (1998).

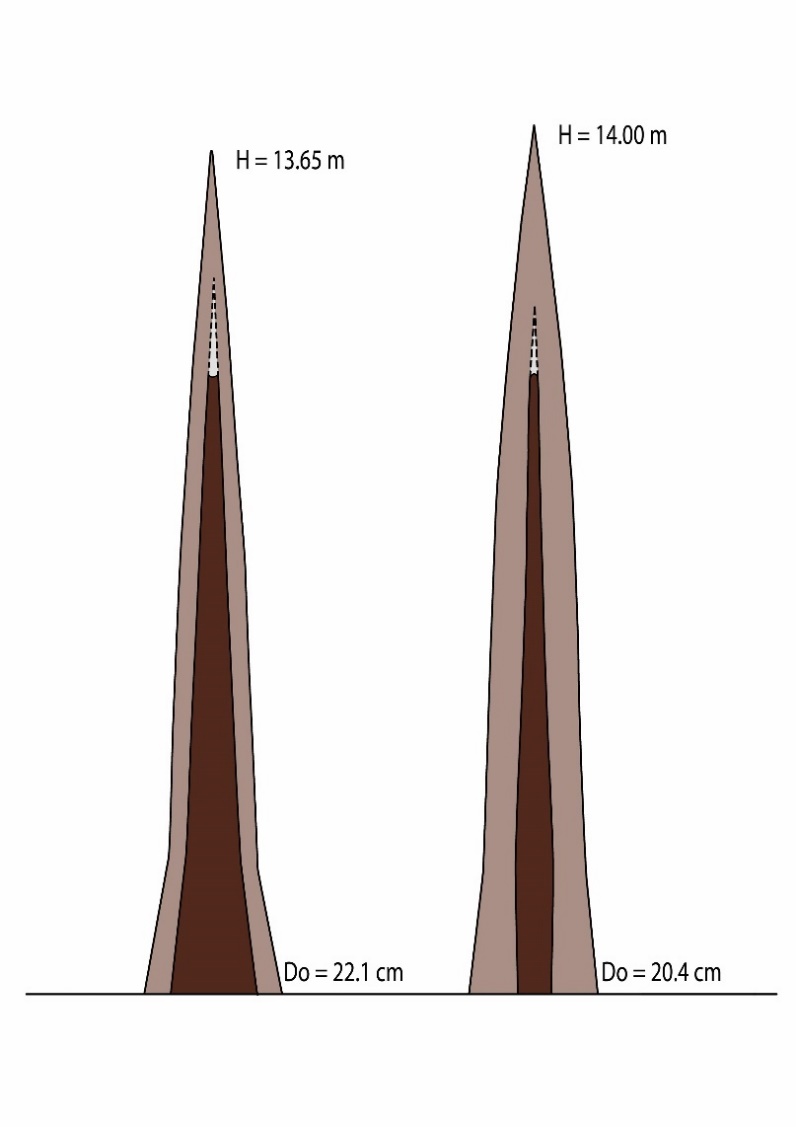

Sapwood is the physiologically active part of the wood. It takes care of water transport and storage of assimilates and water, coordinated by the living parenchyma cells (see 12.3.3). Water transport and other physiological processes occur mainly in the most recently formed tree rings under the bark (Figure 12-10) because physiological activity declines from the bark towards the pith. At a certain moment, supporting this less efficient inner part of the stem might cost the tree more resources than it provides benefit to contribute to vital functions. Some, often long-living, species like pedunculate oak or Douglas fir (Figure 12-15) developed the capacity to transfer this less efficient inner part of the sapwood into dead heartwood. Heartwood formation is a genetically determined process and starts when the trees are about 15 to 30 years old. This means that heartwood forming species keep an outer sapwood area that contains 15 to 30 physiologically active tree rings. However, depending on species and site conditions the number of sapwood rings can vary. Trees that do not form heartwood (like silver fir, beech, ash, poplar) show decreasing physiological activity from the outer to the inner stem parts.

The transition from sapwood to heartwood is a programmed process initiated by hormones and driven by the parenchyma cells in the sapwood-neighbouring ring(s) (transition zone) that will be transformed into heartwood. To make the future heartwood impermeable, the tracheids and vessels are blocked, with the pits between the cells irreversibly sealed and the vessels plugged with gum-like substances or tyloses (Figure 12-13). Additionally, the parenchyma cells produce species-specific aromatic substances (extractives) that penetrate and are fixed in the cell walls and partly fill the lumen of all wood cells, making the resulting heartwood more resistant to decay. Eventually, the parenchyma cells die off.

The tissue structure of heartwood does not differ from sapwood, but it contains higher concentrations of extractives, the chemical properties changes, and the wood can get somewhat denser. Because of pit closure and formation of tyloses, the wood becomes significantly less permeable. The oxidation of the extractives often results in a distinct darker colour of heartwood in comparison to sapwood (Figure 12-10). As the chemical composition partly depends on site conditions, a large variety in species-specific extractives and thus heartwood colours can be found between and even within species. And there are also species, such as spruce, that show no colour difference between sapwood and heartwood at all.

Besides colour, the type of extractives and their toxicity to wood degrading organisms differs between species, causing interspecific differences in heartwood resistance to decomposition. The inner wood of heartwood forming species is generally better protected from decomposition by microorganisms than the inner wood of non-heartwood forming species. This is why the latter more often have hollow stems. In the living tree the fully water-saturated sapwood is not vulnerable to decomposition due to a lack of oxygen. Once the sapwood is not water saturated any more, e.g. due to local mechanical injury or due to felling of the tree and drying of the wood, sapwood becomes more susceptible to decomposition than heartwood. This high decomposability of sapwood compared to heartwood is caused by the lack of protection by extractives and the higher nutrient content due to the presence of living parenchyma cells.

Species that are genetically not programmed to form heartwood can form false heartwood. Well-known examples are the red heartwood in beech or the brown heartwood in ash; poplar and willow are known to form wetwood, which is false heartwood infected by bacteria. It has a sour scent and a high moisture content. The formation of false heartwood happens spontaneously, rather than being programmed, e.g. after injury to the roots, branches, or trunk. False heartwood causes discolouration in the centre of the stem, but this discolouration is often irregular shaped and does not follow the boundaries of tree rings. The formation of false heartwood resembles the processes involved in wound reactions (see 12.3.8). Cells are blocked by sealing of the pits and plugging the vessels with tyloses or inhibitory compounds, making false heartwood impermeable. Extractives may cause discolouration, but – in contrast to programmed heartwood formation – these are not fixed to the cell wall. As a result, false heartwood does not show the higher resistance to decay as known from heartwood (see box on Wood Quality).

Figure 12-15: Distribution of heartwood (dark) and sapwood (light) along the trunks of a Douglas fir (left) and Scots pine (right). The pine has a lower taper in the heartwood core compared to the Douglas fir. D0 = diameter at stem base. Adapted from de Hough (1925).

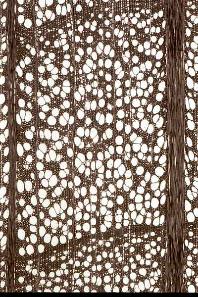

12.3.6. Branch wood and root wood

The structure of wood in branches, stem, and roots differs according to the function of these organs in the tree (Figure 12-16). Branch wood largely consists of juvenile wood and contains a lot of reaction wood (see 12.3.7). Although differences occur between species, some general trends can be found: the cells in branch wood are shorter, smaller, and have thicker cell walls compared to stem wood. Branch wood of conifer trees has more resin canals to prevent the penetration of microorganisms in case of branch breakage. The density of branch wood is often higher than in stem wood, mainly due to presence of smaller cells with smaller lumen, but this does not translate into better technological properties due to its inhomogeneous structure.

Root wood differs from branch and stem wood by having a higher proportion of parenchyma (more rays and axial parenchyma) and larger water conducting vessels or tracheids with more pits. In ring-porous species, such as pedunculate oak, the large difference in early- and latewood vessel size (Figure 12-10) disappears, which creates a more diffuse-porous structure in roots (Figure 12-16). The structure of root wood is related to its main functions, i.e. high assimilate storage capacity and efficient water transport. To ensure mechanical stability at the stem base, coarse roots hold long fibres (broadleaved trees) and tracheids (conifers) often with thick cell walls. Differences in wood structure also occur between vertical and horizontal roots. Compared to horizontal roots, vertical (tap) roots generally have larger vessels for efficient water transport towards the stem. Horizontal roots, apart from water uptake, also need to handle mechanical stresses and thus contain more reaction wood with smaller vessels or tracheids (see 12.3.7). Overall, root wood is lighter, displays more shrinkage, and has lower tensile strength in relation to stem wood.

Figure 12-16: Differences in wood structure in stem wood (left) and root wood (right) in oak (Quercus robur) (top, 32x), beech (Fagus sylvatica) (middle, 25x), and Siberian larch (Larix sibirica) (bottom, 40x). Photos by Fritz Schweingruber.

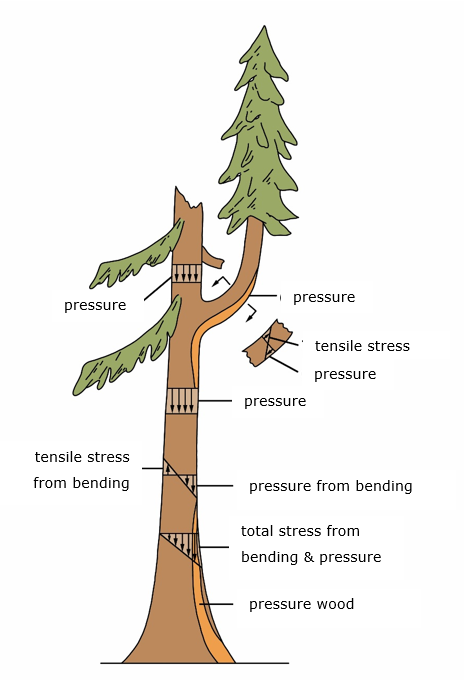

Once wood is formed, its structure remains unchanged, except for heartwood (see 12.3.5). This means that the tree cannot instantaneously adjust to external mechanical stress -due to wind, unstable soil or branch breakage- by changing the properties of its existing wood to adapt to the new situation. For example, a stem that got into a leaning position after a storm cannot turn back to an upright position by changing its existing stem tissue. Also, cracks that occur in the centre of the trunk cannot be closed because there are hardly living cells present to repair the wound. Trees adapt to mechanical stresses in the longer term by adapting the structure of the newly formed growth rings. Triggered by the type and distribution of hormones, the cambium forms new wood around the stem circumference that differs in thickness and structure, compensating the mechanical stress by literally “moving” tree organs and change the stem position. Stems thus may even get back into an upright position, and branches can be oriented towards the light after gap formation.

The newly formed layer of wood is called reaction wood. Reaction wood is formed in trunk, branches, and roots (Figures 12-17, 12-18). Related to their difference in wood structure, conifer species developed a different strategy to respond to mechanical stress than broadleaved species. When a tree starts to lean, conifers develop compression wood on the lower side of the trunk to push the tree into a stress-free, upright position (Figures 12-17, 12-18a/b). Conversely, broadleaved trees form tension wood on the upper side of the trunk. Conifers push back the structure, whereas broadleaved trees use a pull-back strategy.

The formation of compression wood and tension wood leads to eccentric growth, with the reaction wood located in the zone with wider annual rings (Figure 12-18a/b). The wood formed at the opposite side of the reaction wood is called opposite wood. On the cross-section of the trunk of conifer species, zones with compression wood can be recognized by a slightly darker brown to reddish colour due to a higher concentration of lignin. The tension wood of broadleaved species is macroscopically difficult to distinguish from normal wood but can be slightly lighter in colour due to a higher cellulose content. Sawn tension wood can have a “woolly” or rough surface.

Under the microscope the tracheids in compression wood have a distinct round shape (Figure 12-18) with spaces between the cells (intercellular spaces). The cell walls are thicker and predominantly consist of an a highly lignified S2. The cellulose fibrils in the S2 are oriented at an angle of approximately 45 degrees to the fibre direction and are characterized by slits running in the direction of the cellulose fibrils. The large angle of the fibrils, together with the higher proportion of lignin, provides compression wood with better compression strength than normal wood, allowing successive layers of compression wood on the underside of tree parts to push them into a different position.

Figure 12-17: Various forces acting on the tree and the formation of reaction wood (in this case, compression wood in a conifer tree). Adapted from Mattheck (1991).

The tension wood in broadleaved trees anatomically differs from normal wood by the presence of fewer and smaller vessels. Most relevant changes can be observed in the cell-wall properties of the fibres. The S1 and S2 are always present but are often thinner than in normal wood, with more cellulose and less lignin. Instead of the S3, tension wood fibres of many tree species (such as poplar, beech, maple) have a thick cell wall layer composed almost exclusively of cellulose. This gelatinous layer or G-layer can sometimes fill the entire cell lumen. The cellulose fibrils in the G-layer, like those in the S2, show a steep microfibril angle that is oriented almost axially. Successive layers of tension wood generate the necessary tensile forces on the upper side of tree parts, causing (re-)orientation of branches or trunks.

The formation of reaction wood has negative implications for wood processing. Eccentric growth leads to reduced yield and quality in veneer and sawn timber (heterogeneous veneer figure and planks with irregular tree ring patterns). The altered chemistry and ultrastructure of reaction wood result in differences in shrinkage and swelling behaviour compared to normal wood, which can cause cracking in round timber. When drying coniferous and broadleaved reaction wood, irregular longitudinal shrinkage occurs that results in wood deformation.

Figure 12-18a: Reaction wood in birch (tension wood). The microscopic image of tension wood is marked by presence of an inner G-layer in fibre cells consisting of cellulose (magnified 400 times). Photo taken by Holger Gärtner

Figure 12-18b: Reaction wood in spruce. The tree once experienced tilting due to wind, and has since produced compression wood (left). The microscopic image of the compression wood (right) exhibits highly thickened cell walls of tracheids with large intracellular spaces among the cells (magnified 400 times). Photos taken by Fritz Schweingruber.

12.3.8.Wound reactions in trees

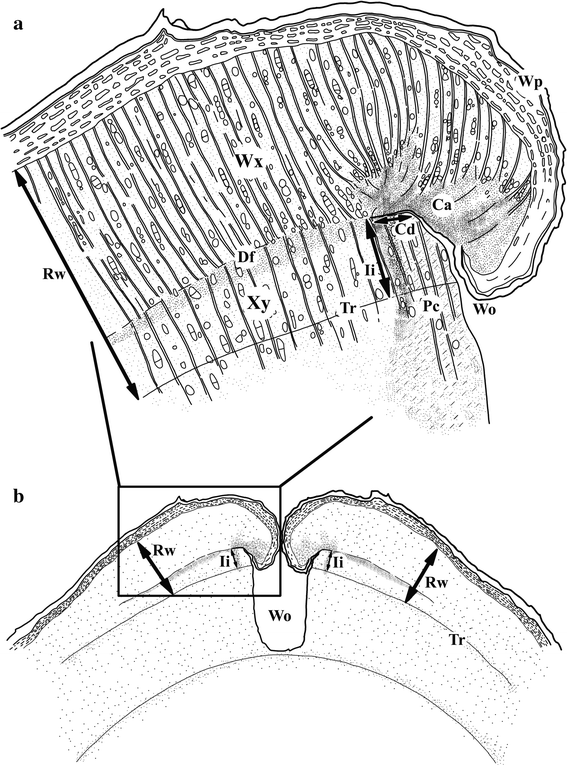

Trees have evolved effective defence mechanisms to protect their physiologically active xylem and phloem after wounding. When trees get wounded —after stem or branch breakage, pruning, insect attack, or other causes—they face the risk of pathogen invasion and decay. Trees do not heal wounds like animals do; instead, their strategy is to compartmentalize and eventually overgrow wounds to preserve structural and physiological integrity (Shigo et al., 1977, Dujesiefken & Liese, 2008). This natural defensive strategy enhances tree longevity, resilience, and safety.

After wounding, air and also microorganisms may penetrate into the wound and cells directly adjacent to the wound. Depending on the depth of wounding different wound reactions may occur:

- When the wound is restricted to the living bark (cortex and phloem) of broadleaved trees, cells adjacent to the wound release inhibitory compounds and then die. Intact cells further away start forming a ligno-suberized layer, after which a wound periderm develops that isolates healthy tissue. Conifers first secrete resin from specialized ducts to isolate the wound.

- If also the cambial zone is affected by wounding, cambial cells around the wound die and adjacent intact cells react by forming callus tissue (traumatic parenchyma cells and wound xylem) that overgrow the wound (Figure 12-19). Wound xylem is characterised by containing more parenchyma cells and narrower and malformed vessels. In broadleaved trees these are frequently connected in radial groups. In addition, density fluctuations may occur close to the wound. In conifers, wound wood consist of malformed tracheids and also traumatic resin ducts can be formed.

- If wounds reach into the sapwood, parenchyma cells secrete inhibitory compounds to form a chemical barrier for e.g. fungal hyphae. Moreover, parenchyma cells can block the vessels by formation of tyloses (see Figure 12-12) or also by secretion of inhibitory compounds. As a consequence, distinctly coloured boundary layers start to form in axial, radial and tangential directions. In conifers the pits between tracheids may close.

- If also heartwood is affected, no further wound reaction can occur as heartwood does not contain living cells. This also means that in trees without resistant heartwood, wood decay may not be halted after it is wounded. In species without heartwood, false heartwood can be formed, e.g. in beech or poplar.

Rates of wound closure differ between species and is related to tree vigour, wound size and the timing of wounding (Dujesiefken & Liese, 2008). In general, fast growing species like poplars or species with a lot of parenchyma cells tend to close wounds quickly. Wound reactions are temperature dependent and therefore clear differences in wound reactions exist between wounds that occur during winter dormancy and those that occur during the growing season. Regardless of the season of wounding, the cambium close to the wound normally dies back. This dieback tends to be more severe if the wound was incurred during winter dormancy. In temperate climates, the formation of wound periderms, callus cells, and wound xylem normally only occurs during the growing season. During the growing season, inhibitory compounds are quickly deposited in the xylem and living bark quickly after wounding, while during winter dormancy this deposition tends to be restricted more to the wound margins. As a consequence, much more wood is affected by wounds that occur during winter dormancy than at the start of the growing season. This has consequences for the timing of pruning.

Figure 12-19: Schematic overview of a transverse section around a wound (Wo) in a tree. The position of cambial dieback (Cd), callus (Ca), wound periderms (Wp), Density fluctuation (Df) and wound xylem (Wx) are indicated. The intra-annual increment (Ii) indicates the position of the cambium at the time of wounding and in relation to the Rw it can provide an indication on the season of wounding. In this illustration wounding occurred during the growing season (Adapted from Copini et al., 2014)

The concept of Compartmentalization of Decay in Trees (CODIT) (Figure 12-20) attempts to explain how decay in trees is isolated – or compartmentalized – and stops or restricts its spread (Shigo & Marx, 1977). More recent, it was suggested that the ‘D’ should better stand for ‘Damage’ or ‘Dysfunction’ as trees respond similarly to decay as to wounds caused by abiotic factors (e.g. branch breakage) or biotic factors (e.g. browsing) (Dujesiefken & Liese, 2008). The CODIT model provides a good but simplified basis to understand how compartmented trees defend themselves by describing four “walls” that trees sequentially form to contain damage (see Figure 12-20):

- Wall 1 (Axial): Following wounding, axial spread is prevented through pit closure between tracheids (conifers) and plugging of vessels with tyloses or inhibitory compounds (broadleaved species). This wall is the weakest, as it can still be broken by wood-decaying microorganism.

- Wall 2 (Radial): Thick-walled, lignin-rich cells in the latewood of tree rings restrict radial invasion toward the tree centre.

- Wall 3 (Tangential): Living ray parenchyma blocks lateral spread by producing toxic substances that form a chemical barrier against some microorganisms, representing the strongest barrier at the time of wounding prior to the formation of the barrier zone (Wall 4);

- Wall 4 (Barrier Zone): Created by the non-damaged cambium adjacent to the wound, the cambium starts to form a wall of callus tissue (Figure 12-19), with a stronger resistance to decay. This wall isolates the original damaged tissue—often visible as healthy exterior wood over a hollow core. Depending on e.g. wound size, tree vitality, and decay, eventually the cambial cylinder can be closed again and the wound gets fully overgrown by newly formed xylem and phloem.

Figure 12-20: Compartmentalization of Decay in Trees (CODIT). The locations of wall 1-4 of the CODIT model are indicated. The location where discoloration occurs within the tree is indicated by the green colour and the area where the tree is responding to the wound is indicted by the red colour. (Adopted from Shigo & Marx, 1977).

12.3.9 Wood – transport tissue in the tree and valuable material for industry

As discussed in the previous sections, the properties of wood enable trees to grow tall and live long. There is striking variation in basic wood structure between conifers and broadleaved species as well as different species to match challenges when growing under various climate- and site conditions. Wood structure changes within the tree as it ages and in response to continuously changing environmental conditions and associated mechanical stresses. The result is that wood has an inhomogeneous structure that holds the legacy of past environmental variation, that has enabled the tree to survive but may at the same time negatively affects the technological wood quality.

For example, specific gradients in cell size of tracheids in conifers and vessels in broadleaved species make that slow growing (narrow tree rings) and fast growing (wide rings) trees of the same species may strongly vary in wood density. Most obvious is the difference between ring-porous species (e.g. oak) and conifer species: fast growing oaks produce tree rings with a large amount of dense latewood and hence heavy oak timber. The wide tree rings of fast growing pines, however, contain a lot of light earlywood and a lower amount of denser latewood which causes the wood to be lighter than the wood of slow growing trees (see Box Wood Quality).

In the field of wood science and technology, the wood of coniferous species is commonly referred to as softwood, and that of broadleaved species as hardwood. This terminology can be misleading as not all conifers or softwoods form soft or light low-density wood and certainly not all broadleaved species form hard wood. For example, hardwood species like poplars or willows are much softer, i.e. have a lower wood density, than, for instance, yew (Taxus baccata). But it is also true that the species with the highest wood density are tropical hardwood species, such as Azobé from Central Africa or Quebracho from South America. However, the terms softwood and hardwood are deeply ingrained in the historical and botanical classification of conifers and broadleaved species and commonly used in wood sciences.

Leaves are the organs that enable trees to intercept light, evaporate water, absorb carbon dioxide, and produce sugars by means of photosynthesis (see chapter 13). Although tree leaves exhibit a tremendous variety of shapes, essentially they all have the same structure. Broadleaved trees generally have broad planar leaves, while conifers have needle- or scale-shaped leaves. An exception to this rule is the conifer ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), with its fan-shaped planar leaves.

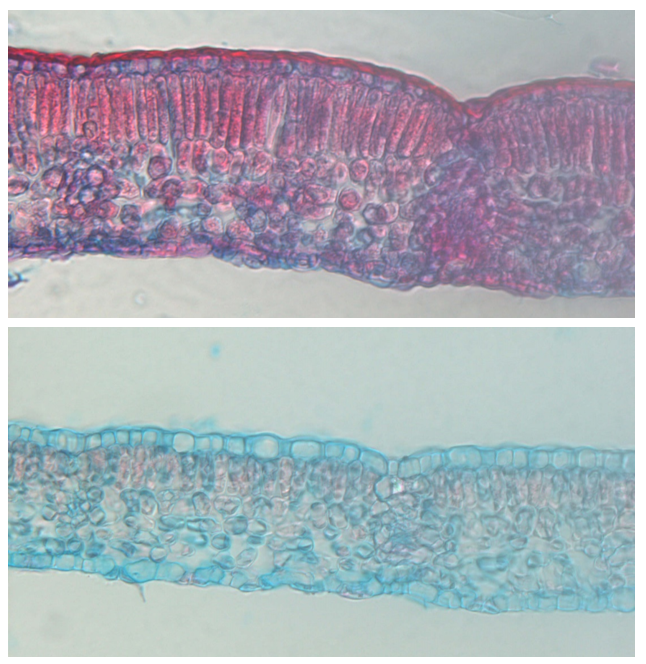

Leaves of broadleaved trees are bordered on the upper and lower sides by the epidermis: a protective layer of cells covered by an additional protective wax layer called the cuticle that prevents water loss from the leaf (Figure 12-21). The inside of the leaf mainly consists of parenchyma cells and is commonly referred to as mesophyll. On the upper side of the leaf, this consists of palisade parenchyma, closely packed elongated cells, one or more layers thick, filled with chloroplasts (leaf chlorophyll). Below that is the spongy parenchyma, consisting of more rounded cells forming a loose structure with numerous intracellular spaces. Veins run through the leaf, containing vascular bundles of xylem and phloem, for transport of water and sugars. The transport tissue is protected by a vascular bundle sheath that contains cells with thickened cell walls providing support to the vein.

Figure 12-21: Schematic representation of the leaf anatomy of a broadleaved tree. Explanation of the letters: A = cuticle, B = epidermis, C = palisade parenchyma, D = spongy parenchyma, E = vascular bundle sheath, F = phloem, G = xylem, H = guard cell of stomata, J = substomatal cavity. Adapted from www.biologycorner.com.

On the lower surface of the leaf, stomata are present as regularly spaced openings in the epidermis (Figure 12-22). When these stomata are open, CO2 can diffuse into the leaf, and water can evaporate into the atmosphere through the substomatal cavity located directly behind the stomata. A stoma consists of two guard cells with an opening in between. To open the stoma, the ion concentration in the guard cells is increased after exchanging, among others, potassium, which causes the absorption of water into the guard cells. This creates tension (turgor) in the guard cells, causing them to move apart and open the stoma. Under unfavourable conditions (e.g., no light or water available), this process is reversed, the tension in the guard cells decreases and the stomata close. The density of stomata per leaf area varies greatly among species but is also dependent on environmental conditions at the site. In sessile oak, for example, the density of stomata decreases as the atmospheric CO2 concentration increases. This enables the reconstruction of past CO2 concentrations by measuring the density of stomata in fossil leaf material (van der Burgh et al., 1993).

Figure 12-22: Stomata on the leaves of common oak (left) and Scots pine (right), photographed using scanning electron microscopy. The top images provide an overview of the distribution of stomata on the leaf surface, with fungal threads of oak mildew running over the oak leaf (magnification 424x). The stomata on the pine needle (625x) are arranged in parallel rows. The details are magnified 2500 times. Photos by Shari Van Wittenberghe.

Needles have a similar overall structure to leaves of broadleaved trees. However, they are much more compact in cross-section, and the mesophyll is often not differentiated into palisade and spongy parenchyma, as is the case with the roundish needles of Scots pine. In the flattened needles of silver fir, however, the mesophyll is differentiated, and a layer of palisade parenchyma is formed on the upper side. The stomata of needles are usually arranged in rows along the longitudinal axis of the needle and are often visible as distinct stomatal lines. The stomata may be present only on the lower side of the needle or over the entire surface. Lastly, as in the wood of conifers, resin canals run through the needles.

12.4.2 Chloroplasts and leaf senescence

Photosynthesis takes place in the chloroplasts, which are filled with chlorophyll, a pigment that absorbs light and releases the energy driving photosynthesis (see chapter 13). Chlorophyll is embedded in specialized membranes called thylakoids, where photosynthesis takes place. Chlorophyll mainly absorbs blue and red light while reflecting green light, giving leaves their green colour. Chloroplasts have their own DNA, which is transferred from the mother plant to the seedling through the seed. This makes chloroplast DNA suitable for reconstructing plant lineages (see chapter 15).

In addition to chlorophyll, leaves also contain other pigments, particularly xanthophyll (yellow), carotene (orange), and/or anthocyanin (red). The function of these pigments is not entirely clear, but they are often associated with the protection of the leaf against UV radiation (Archetti, 2009). Before the leaves of deciduous species are detached from the tree in autumn, the chloroplasts break down, and the nutrients present in the leaves or needles are partially reabsorbed and stored in the parenchyma (resorption or retranslocation) of the branches. This process primarily involves the resorption of magnesium and nitrogen from chlorophyll and amino acids. As chlorophyll breaks down, other pigments become more prominent, resulting in the typical autumn colours of trees. After nutrient resorption is complete, a thin layer of cork is formed in the abscission layer at the base of the leaf stalk, causing the leaf to break off from the twig and leaving a leaf scar. An abscission layer can also form by locally breaking down cell walls or only the middle lamella.

Leaves exhibit a wide variety of shapes. Leaves of broadleaved trees can be simple or compound, pinnately or palmately compound, with smooth or serrated margins (edges), oval or triangular, and so on. Little is known about the possible ecological significance or function of different leaf forms. However, there appears to be a correlation between the proportion of species with smooth-margined leaves and the average annual temperature of an area. The higher the temperature, the higher the percentage of leaves with smooth margins. This relationship is so strong that it can be used to estimate the average temperature (Kowalski, 2002). Conifers have round, triangular, or flat needles, or they are scale-like, as in Thuja and Chamaecyparis. Due to their small leaf surface area relative to leaf volume, most conifers are well adapted to drought and frost.

To protect leaves from herbivory, they often contain high levels of tannins (oak, beech), cyanide compounds (black cherry), or terpenes (conifers), which make the leaves unappetising, difficult to digest, or even toxic. Holly defends itself with spines along the leaf margin, with leaves on taller plants losing their spines. Grazed plants have more spines on their leaves compared to ungrazed plants (Obeso, 1997). Young leaves, however, are soft and palatable.

Leaves growing in full sunlight are thicker than leaves on the same tree growing in the shade. This difference between sun leaves and shade leaves is primarily caused by the presence of an additional layer of palisade parenchyma in sun leaves, allowing them to make optimal use of the abundant light. Sun leaves are often smaller than shade leaves, with thicker cell walls in the epidermis and a thicker cuticle to prevent water loss due to overheating in direct sunlight (Figure 12-23).

Figure 12-23: Cross-sections of leaves from a young beech tree. The lower leaf grew in the shade of a large beech and contains a thin layer of palisade parenchyma. The upper leaf grew on a plant at a height of 28 m in full sunlight and has a clearly thicker layer of palisade parenchyma, as well as a thicker epidermis and epicuticular wax layer. Photos by Shari Van Wittenberghe.

12.5 Structure of the fine roots

Roots can be separated into different categories based on their functions that are in turn reflected by large differences in their lifespans, morphology and anatomy. Previously, roots were typically separated into two groups based on their diameter, where coarse roots are those with a diameter < 2 mm and fine roots those with a root diameter ≤ 2 mm. These diameter classes were assumed to reflect functional differences. The older, long-lived coarse roots provide anchorage in the soil, store organic and inorganic substances, and transport resources within the plant, whereas the young fine roots would be solely involved in the uptake of soil water and nutrients. More recent studies, however, show that large functional variation still exists within the fine-root category, as some fine roots are only marginally responsible for resource acquisition, and predominantly transport resources. To more accurately represent this functional diversity, the traditional ‘fine root’ category is now further separated based on root order, where the most distal, unbranched roots are first-order roots (or root tips), second-order roots begin at the junction of two first-order roots, etc. As such, the first-, second-, and third-order tree roots are the absorptive (fine) roots, whose primary function is to acquire soil resources; the higher order fine roots are designed for resource transport rather than acquisition.

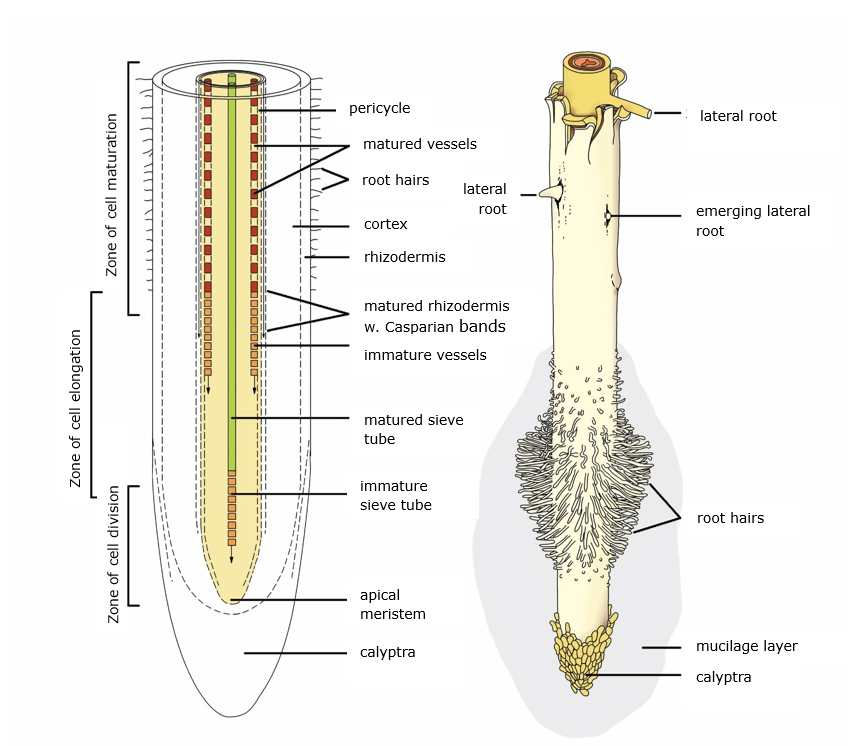

The different functions of the root categories are paralleled by structural differences. Firstly, the functions and structure of coarse roots are broadly similar to those of the stem and are thus explained in section 12.3. Secondly, the fine root category as a whole consists, from the outside to the centre of the root, of the following tissues (Figure 12-24): the root epidermis (or: rhizodermis), cortex, endodermis, pericycle, and central cylinder. The presence, development and/or size of these structures vary with root ontogeny and order as the primary function of roots gradually shifts from resource uptake from soil to root to resource transport within the roots.

The root epidermis forms the outermost layer of both the transport and absorptive roots, where it facilitates the absorption of water and mineral substances, prevents the loss of these resources to the soil, and serves as a first barrier against soil microorganisms. Along the absorptive root, root hairs develop as cylindrical extensions of the root epidermis. They vary in length between 0.2 and 2 mm, are a single cell wide, have a lifespan of only a few days and are continuously regenerated from the root tip. As they greatly enhance the surface area of the roots and thus the soil volume that can be explored, root hairs may contribute considerably to the acquisition of (especially immobile) nutrients. Similar to shoots, the root epidermis is replaced by the periderm (see section 12.2.2) which further protects roots from water loss and pathogen entry during secondary (i.e., radial) growth of fine roots.

Further towards the centre of the root lies the root cortex (Figure 12-2) which consists of round parenchyma cells with numerous intercellular spaces. Cortical tissue is essential for water and nutrient uptake by absorptive roots, and the cortex provides colonization space for (especially arbuscular) mycorrhizal fungi that provide plants with soil resources. As such, the size of the cortex (relative to the root cross-sectional area) is largest in absorptive roots and decreases, or is shed entirely as roots undergo secondary development and become more involved in, and optimized for, resource transport.

The innermost layer of the cortex is the endodermis. This is a thin layer of relatively small, closely packed parenchyma cells that form a diffusion barrier of lignin and suberin called Casparian strips. It acts as a gateway for water uptake by forcing (solutes in) water through the symplast rather than apoplast. While the former pathway (that passes water through the cell membrane) is generally slower than the latter (that passes water through only the cell walls), it is more selective and can prevent unwanted solutes (e.g., heavy metals, salts) and soilborne pathogens from entering the vascular system. Like the epidermis, the endodermis allows water to flow towards and not away from the central cylinder. As roots undergo secondary development, more suberin is deposited in the endodermis further reducing water loss from transport fine roots.

Inside the endodermis lies the central cylinder of the root. Its first, outer layer is the pericycle that consists of meristematic tissue and is responsible for the formation of new, lateral roots and secondary bast. During secondary development, the pericycle also forms cork tissue to prevent water loss (as well as water uptake), decreasing the uptake capacities of transport roots. In the middle of the central cylinder, embedded in parenchyma tissue, lie the vascular bundles. Absorptive roots generally contain only primary xylem (i.e., initial conducive cells to transport water to higher order roots) and generally show no or little secondary development. Fine roots that have undergone secondary development have secondary xylem with well-developed conduits and highly lignified cell walls in a relatively large stele (relative to the root cross-sectional area) to facilitate upwards transport of water and nutrients. Interspersed among them are strands of primary and secondary (in roots that show secondary development) phloem for the transport of photosynthesis products to the roots.

Figure 12-24: General structure of a root tip. See text for further explanation. Adapted from Raven et al. (1999).

Trees reproduce through seeds that develop after fertilization of the (female) flowers. Many trees bloom inconspicuously, and only a handful of European tree species exhibit exuberant flowering with prominent petals, such as lime, apple, pear, rowan, elderberry and hawthorn. This is related to the fact that, for most species, flower pollination occurs by wind, so there’s no need for special adaptations to attract pollinators, such as large petals and fragrant flowers.

A large portion of the broadleaved flowering tree species in our forests belong to a small number of families: the Salicaceae or willow family (Salix and Populus), the Betulaceae or birch family (Betula, Alnus, Corylus, Carpinus), and the Fagaceae or beech family (Fagus, Quercus, Castanea). These families produce unisexual catkins, with male and female flowers occurring in separate clusters on the tree (Figure 12-25). In the willow family, the species are dioecious, with male and female catkins on different individuals. The ash tree (from the Oleaceae or olive family) is also dioecious. The other families mentioned above are monoecious, with male and female catkins on the same tree. Species from these families generally bloom very early in spring, either before or at the same time as the leaves emerge. The pollen from the male flowers is transferred to the female flowers by wind. The exception is the sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), which flowers in the summer with spike-like inflorescences predominantly bearing male flowers, and a few female flowers at the base that are partially pollinated by insects.

Figure 12-25: Flowering hazel (Corylus avellana) with male (catkins) and female (red) flowers. Photo by Leo Goudzwaard.

Pine trees have unisexual flowers cones, with female flowers developing into seed cones. In Scots pine, female flowers appear as small cones at the end of the young shoot. Male flowers are located at the base of the young shoot. The flowers are wind-pollinated and fertilization takes place a year later. The cone continues to grow and ripens in the second year, opening during winter and early spring. Late in spring, one can observe a sequence of flowers, immature cones, and old open cones on the same branch. Other conifers from the genera Picea, Pseudotsuga, and Abies have a similar flowering process and also produce cones. Notably, Abies cones do not hang from the branch but stand upright. Upon ripening, the cones shed their scales one by one, releasing the seeds.

Juniper is dioecious, and its female flowers produce a cone that forms a false fruit with fused fleshy scales enclosing the seeds. Yew is also dioecious, and its unisexual flowers develop in the leaf axils of the young twigs during autumn. The female flower consists of an ovule that develops into a single seed surrounded by a red, fleshy covering called the aril. This sweet and tasty aril is the only non-toxic part of the yew. Animals may eat this, digesting the aril while the seed passes intact through the digestive tract.

Trees produce a wide variety of seeds and fruits (Figure 12-26). Most seeds and fruits have special appendages or coverings that serve a function in seed dispersal. In willows and poplars, the seeds are attached to fluffy structures, allowing them to be dispersed by the wind over tens of kilometres. Seeds with wings, such as those of birch, pine, spruce, maple, and ash, can also travel considerable distances through the air. Seeds contained within berries are mostly dispersed by birds or mammals. Nuts, acorns, and beech nuts lack obvious special appendages; they have a high nutritional value and an important food source for many animals. Many animals hide such seeds temporarily which greatly facilitates the dispersal of these species.

Figure 12-26: Some fruits of trees with their respective seeds. From left to right: beech, small-leaved linden, sessile oak, pedunculate oak, hornbeam. Photo by Leo Goudzwaard.

Trees undergo significant changes in shape and size during their life cycle. These changes are driven by primary processes (height growth and crown development) and secondary growth processes (growth in thickness) discussed in the previous paragraphs. The way primary shoots grow in length and ramify determines the shape of the crown. Simultaneously, crown growth exerts increasing mechanical stress on branches and the trunk, which is accommodated by the formation of new xylem. Ultimately, the resulting tree structure is an interplay of internal growth rules, external environmental factors, and optimization of mechanical stability.

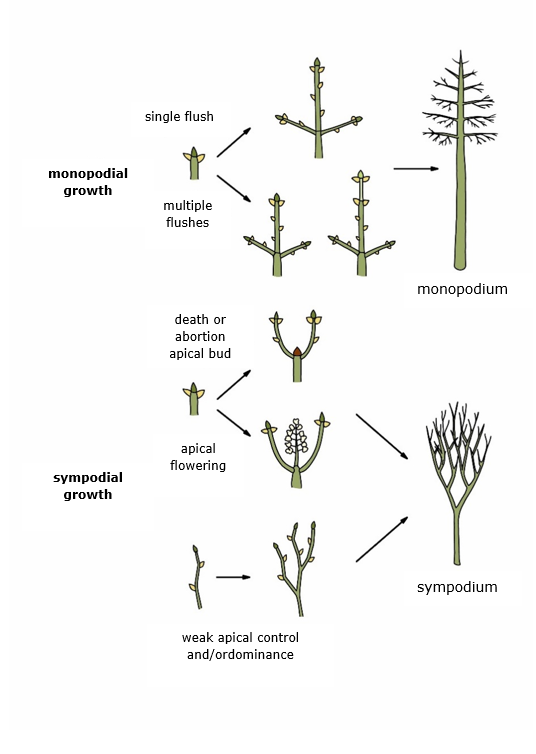

The appearance of a tree is primarily determined by the way it branches. The terminal shoot provides height growth and creates the central axis around which the trunk grows. The shape of the trunk is, therefore, the result of the way the terminal shoot grows upward, and the distribution and growth of the lateral branches. Tree species with apical meristems in the terminal shoot that grow continuously create a monopodium (Figure 12-27). As long as the apical meristem remains undamaged, a monopodial trunk with a straight central axis develops. Many coniferous trees inherently have straight trunks due to their strongly dominant terminal shoot, controlling the growth of lateral branches (apical dominance and control, see chapter 13). On the other hand, in many broadleaved trees, the growth of the terminal shoot is much more flexible, and the control over lateral branch growth is less strict, resulting in more irregular crown shapes compared to conifers and a less defined central axis in their trunks. This, in turn, offers an evolutionary advantage to broadleaved trees, as they are much better at directing their crown growth towards areas with higher light availability and filling the three-dimensional space with photosynthesizing leaf material.

When the apical meristem regularly dies due to external factors (frost, browsing, salt damage, etc.) or internal factors (genetically programmed apical bud abortion or terminal flowering), a sympodium is formed, allowing extensive branching of the trunk leading in a dissolving central axis (Figure 12-27). If this branching of the trunk occurs low on the tree, we refer to these individuals or species as polycormic. In case of apical bud loss, height growth can be taken over by one or more lateral branches. In trees with a more upright central axis, this can lead to forking of the stem (Figure 14-1).

Figure 12-27: The formation of a monopodium (straight central axis) and a sympodium (branched central axis) in trees.

Branches generally exhibit a clear growth direction, and there can be a pronounced difference between the growth direction of the terminal shoot and that of the lateral branches (Figure 12-28). In most species, the terminal shoot shows distinct vertical growth. In these orthotropic branches, the shoot grows vertically, and buds and leaves are arranged in a spiral around the branch axis (e.g. pine, spruce, oak, ash). In several other species, the terminal shoot does not grow vertically but in an angle, and has buds arranged in a plane, alternating along the shoot. This is referred to as a plagiotropic branching direction (e.g. beech, elm, sweet chestnut, hemlock). In such species, all branches are plagiotropic.

The lateral branches of orthotropic species may also display orthotropic growth, which makes them grow almost straight upwards (e.g., in poplar, ash, oak, pine) but the branching angle may also become distinctly horizontal, as in spruce or fir. Such branches are secondary plagiotropic, since the buds and leaves are arranged in a spiral around the branch axis (as in orthotropic branches), but the twigs and leaves are bent into a flat plane. In plagiotropic species, the lateral branches are also plagiotropic, which can thus be considered primary plagiotropic.

|

|

Figure 12-28: Growth direction of shoots. Left: orthotropic terminal shoot and lateral branches of Scots pine. Right: plagiotropic lateral branches of Douglas fir. The needles and buds of Douglas fir are spirally arranged around the twig, but the needles bend towards a plane, resulting in secondary plagiotropy. Photo by Jan den Ouden.

12.7.1.2 Long shoots and short shoots

Branches within a tree can also vary significantly in length. Branches with normal length growth are referred to as long shoots to distinguish them from reduced short shoots (Figure 12-29). Short shoots have a similar shoot structure with metamer segments as long shoots, but they have reduced internodes, giving them a compact appearance with closely spaced leaves. Long shoots are important for light exploration and crown expansion. In contrast, short shoots are important for light exploitation by producing a large leaf surface area without requiring much investment in branch growth.

Figure 12-29: A branch of a Japanese larch in early spring. Short shoots grow on the long shoot from the previous year, where the new needles emerge. The scars left by the needles of the previous year are still visible on the long shoot. Photo by Jan den Ouden.

12.7.2 Quantitative tree models