Chapter 11: Changes in resource supply and demand – Download PDF

Authors: Bas Lerink, Nicola Bozzolan

Intended learning level: Basic

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

NOTE: this text is a complete draft, which will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

|

Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

|

European forests have a long history of sustainable forest management. Europe has the highest percentage of managed forests among all continents, while the forest sector has an important role in the economy of many European countries. Simultaneously, European forests are under pressure due to effects of climate change. Climate extremes like summer droughts and warm winters reduce the productivity and vitality of the forests, while also negatively affecting harvesting operations. Next to this, policies on regional, national and European level increasingly affect forest management. In this chapter, we will dive into changes in resource supply and demand from European forests. |

Table of Contents

11: Changes in resource supply and demand 1

11: Changes in resource supply and demand 2

11.1 Development of wood supply 2

11.1.4 Recent developments and consequences 7

11.2 Development of wood demand 7

11.2.1 Evolution of European wood demand over time 7

11.2.2 Timber assortments and wood industries 8

11.2.3 Timber flow: from the forest to primary processing 10

11: Changes in resource supply and demand

European forests have a long history of sustainable forest management. Europe has the highest percentage of managed forests among all continents, with 75% of the total forest area being available for wood supply. The forest sector has an important role in the economy of many European countries, especially in Scandinavia. Simultaneously, European forests are under great pressure due to effects of climate change. Climate extremes like summer droughts and warm winters worsen the productivity and vitality of the forests, while also negatively affecting harvesting operations. Next to this, policies on regional, national and European level also increasingly affect forest management. In this chapter, we will dive into changes in resource supply and demand from European forests.

11.1 Development of wood supply

Forests currently cover ca. 227 million hectares, which is almost 35% of the total EU land area (SOEF, 2020). More than one third of the European forest area is located in Northern Europe. Central Europe also harbours large forest areas, while the West coast of Europe has a smaller fractional cover of forest. The three most forested countries are Sweden, Finland and Slovenia. The three least forested countries are Malta, Ireland and the Netherlands.

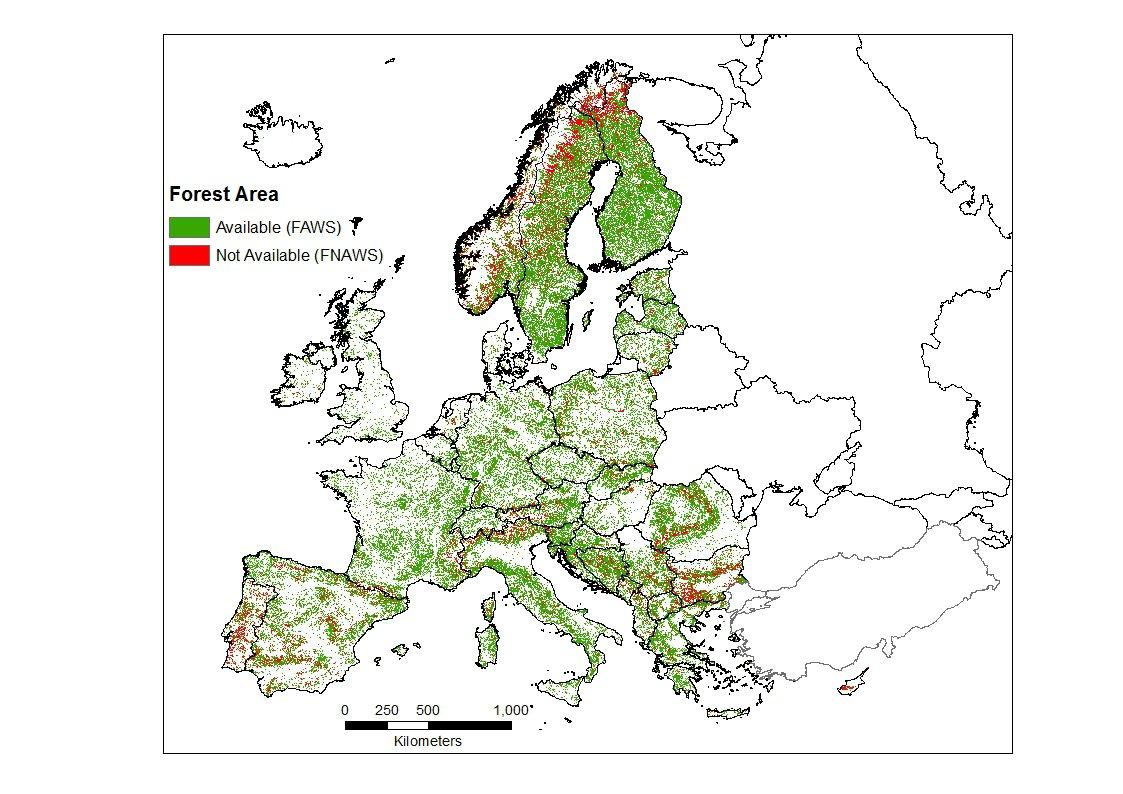

Not all forests are suitable for commercial wood production. The forest area can generally be split into three categories: forest available for wood supply (FAWS), protected forests and forests with limited accessibility. FAWS is commonly determined by means of an exclusion approach: the area of forest that is not protected and does not have limited accessibility is categorized under FAWS. Pucher et al. (2023) determined that FAWS amount to 75% of the European forest area. The remaining forest area either has limited accessibility (21%) or a protection status (4%). Figure 11-1 shows the forest area in Europe. Information on the division of forest area under these three categories per country is presented in Table 11-1.

Figure 11-1: Forest area in Europe, separated between forest area available for wood supply (FAWS) and forest area not available for wood supply (FNAWS) (Avitabile et al., 2018).

The forest area in Europe has increased since World War II, thanks to afforestation programs, forest protection laws and land abandonment. The forest area increased primarily between 1950 and 1970 (Gold et al., 2006). After 1970, the increase slowed down in most European regions, except for Western Europe. More recently, the increase in forest area also slowed down in Western Europe. The curbing of the general trend of forest area increase in Europe is mainly due to land use competition and less interest in timber self-sufficiency.

Table 11-1: Summary of the forest area in Europe (all 34 countries considered) and distinguished by geographic regions and countries. The regions are defined according to the State of Europe’s Forests (FOREST EUROPE, 2020). ‘Forest not available for wood supply’ (FNAWS) comprises protected forest where commercial harvesting is prohibited as well as forest areas with limited accessibility (Lim. Accessibility). All other forest areas are considered as ‘forest available for wood supply’ (FAWS) (Pucher et al., 2023).

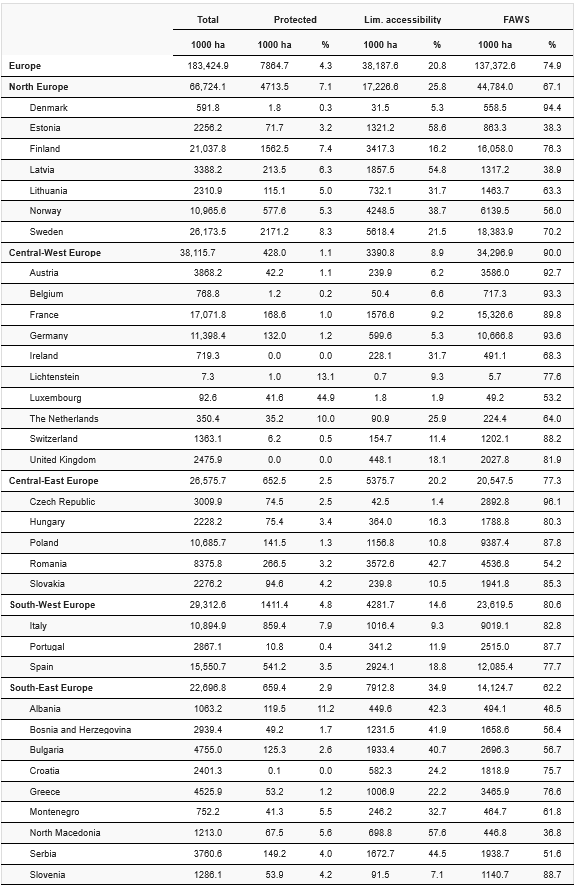

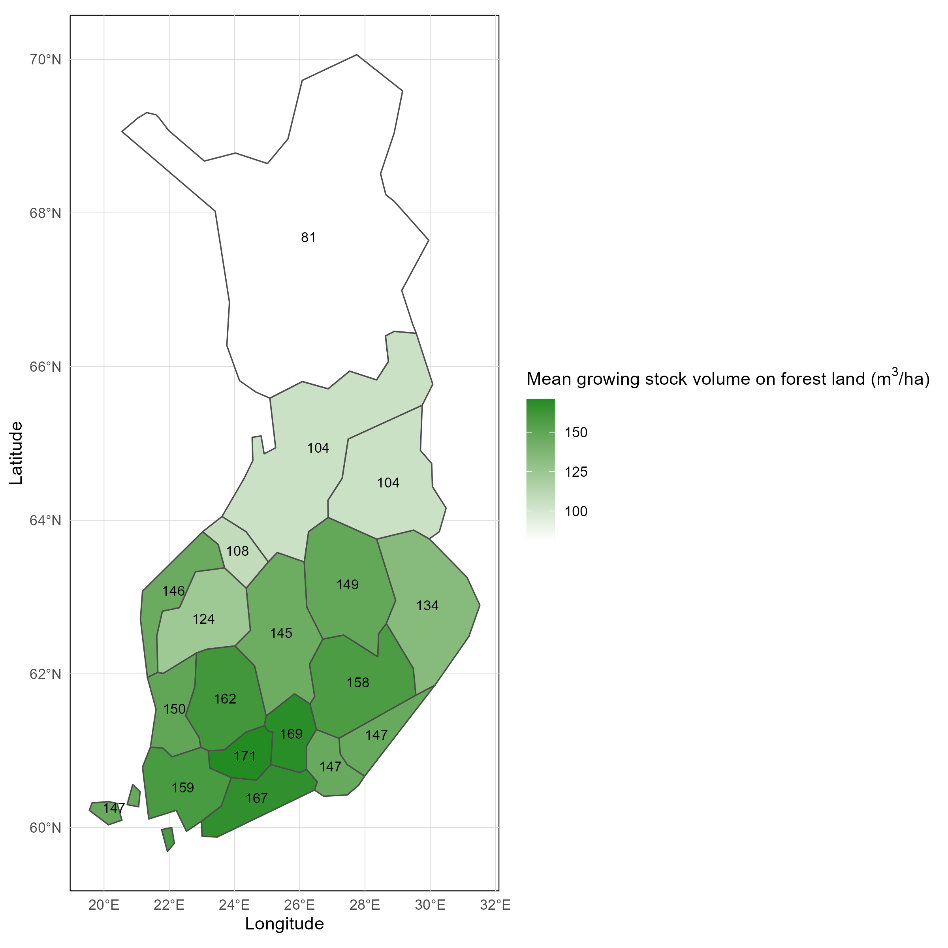

Growing stock is defined as the total volume of stemwood in the living trees in a forest. Quantifying the growing stock of a forest provides valuable information for commercial wood production, carbon sequestration estimates and forest productivity. The average growing stock varies greatly between European biogeographical regions (see Figure 11-3). Generally, the average growing stock in countries from the Mediterranean Basin is relatively low (ca. 100 m3 ha-1), due to poor site conditions and less active forest management. The largest average growing stock values can be found in Alpine and Continental Europe (ca. 300 m3 ha-1), due to temperate climate and production-oriented forest management. Boreal forests have relatively high average growing stock values in the industrially managed southern parts, but this decreases along a South-North gradient due to the cold climate. This can for instance be seen in the results of the 13th cycle of the Finnish NFI (Korhonen et al., 2023), see Figure 11-2.

Figure 11-2: Mean growing stock volume on forest land (m3/ha) in Finland (based on Korhonen et al., 2024)

Similar to the forest area, the growing stock has also increased considerably in European forests since World War II and the rise of sustainable forest management (SFM). The growing stock in European forests has almost doubled in the period 1950-2000 (Gold et al., 2006). An increase in growing stock can only happen if the sum of fellings and natural mortality is smaller than the gross increment of wood, leading to a positive net annual increment. This has structurally happened in Europe over the past decades. An important factor in the increase of the growing stock is the development of the European forests over age classes. Older and more stocked forests were for a large extent cut or destroyed during and after the World War II. This caused a skewed age class distribution of forests throughout Europe, with a tendency towards the younger forests. These younger forests were able to grow to maturity during the second half of the 20th century, with a rise in overall growing stock as a result.

Figure 11-3: Current growing stock for a set of 15 countries, as modelled by the forest resource model EFISCEN-Space (Schelhaas et al., 2022, Nabuurs et al., 2007)

The annual increment is commonly defined as the yearly increase in volume of wood in a tree or stand of trees. It is an important factor to assess a.o. the vitality of a tree or forest stand. Vitality can be defined as the overall health of a tree or forest stand. It can grow well, resist damage from pest, diseases or storms and can recover after stress. The general trend for individual tree growth is an accelerating growth rate in the young phase, a constant rate in the maturity phase and a saturation rate in the senescent phase (ref to Ch 14: Growth). This pattern is also visible in the growth development of European forests over the past decades, with accelerating growth in the first decades after WOII and a more constant growth rate in subsequent decades. Next to age, extended growing seasons and CO2- and N-fertilization are also considered to have positively influenced this growth pattern.

Recently, a decline in wood increment has been observed in many European countries, although there are diverging regional trends (Pretzsch et al., 2023). Reasons for this decline in growth are manifold. For example, in Finland the decline in volume growth can partly be attributed to ageing of the abundant pine stands (Henttonen et al., 2024). Nabuurs et al. (2013) found that the decrease in increment also leads to saturation of the carbon sink, which is an important function of European forests.

11.1.4 Recent developments and consequences

Forests in many European regions are currently underutilized relative to their potential yield (Lerink et al., 2023). In these regions, harvest rates are below the increment, meaning that there is still some theoretical potential for an increase in wood supply. However, the realistic potential is considerably lower, due to factors such as reluctant private forest owners, limited accessibility and regulatory constraints. Additionally, climate change impacts and aging forest in parts of Europe further reduce this potential. Maintaining or even increasing wood supply from European forests will require widespread implementation of climate smart forestry measures and large scale forest restoration.

An example of a climate smart forestry measure could be mixed-species planting or underplanting in low-productivity forests. The impacts of natural disturbances could be further mitigated by reducing fuel in the forests and training forest managers to identify and manage tree pests and diseases. Forest restoration, on the other hand, could involve restoration of degraded agricultural landscapes. This can be achieved by planting drought tolerant tree species, that over time can provide a sustainable source of wood, while restoring ecosystem functions.

11.2 Development of wood demand

11.2.1 Evolution of European wood demand over time

Wood demand is influenced by various factors, including demographic change, economic growth, regional development, policies, and technological progress. In Europe, wood demand has evolved significantly over the centuries. In the pre-industrial era, wood was the main source of heat and an essential material for construction and shipbuilding. After World War II, reconstruction efforts and rising living standards led to an increased demand for wood resources across Europe. In recent decades, digitalization has reduced the demand for graphic papers, while packaging and tissue products have grown in response to e-commerce and lifestyle changes (Hetemäki et al., 2022). Bioenergy, including pellets and other biomass fuels, continues to play a major role in the EU’s renewable energy strategy, although it raises debates about sustainability and competition with material uses (Mubareka et al., 2025). At the same time, innovative wood-based products such as engineered wood and biobased chemicals are expanding rapidly (Hetemäki et al., 2022; Verkerk et al., 2021). Overall, demand is expected to continue increasing, which will likely intensify competition among sectors and call for a more efficient use of available resources.

11.2.2 Timber assortments and wood industries

Wood is classified into assortments based on its properties and intended use. In Europe, a first key distinction that can be made is by species type: conifers, also known as softwoods, and broadleaves, known as hardwoods. The forest industry has traditionally specialized in processing conifers, as they are well-suited for sawing due to their uniform structure, fewer branches, and ease of cutting. Although broadleaves are also used in industrial processes, they constitute a smaller proportion. In 2023, the EU-27 produced 353 million m³ of industrial roundwood, of which approximately 80% was conifer and 20% was broadleaf (Figure 11-4).

Figure 11-4: Industrial roundwood production in the EU-27. The blue line represents production of coniferous industrial roundwood, while the orange line represents production of non-coniferous industrial roundwood (FAOSTAT, 2025). Values are displayed in millions of cubic meters (Mm³).

Wood resources are further classified into assortments based on their intended industrial use. In general, roundwood refers to the main tree stem, harvested from the forest with or without bark. Within this category, we distinguish between fuelwood and industrial roundwood. Fuelwood usually consists of lower-quality logs that are split, curved, or damaged, as well as branches and other tree parts harvested for energy. It is used for cooking, heating, or power production. Industrial roundwood, by contrast, includes all logs suitable for industrial processing, such as sawlogs, veneer logs, pulpwood, and other assortments used in manufacturing (for a complete description of the classes refers to UNECE, 2025).

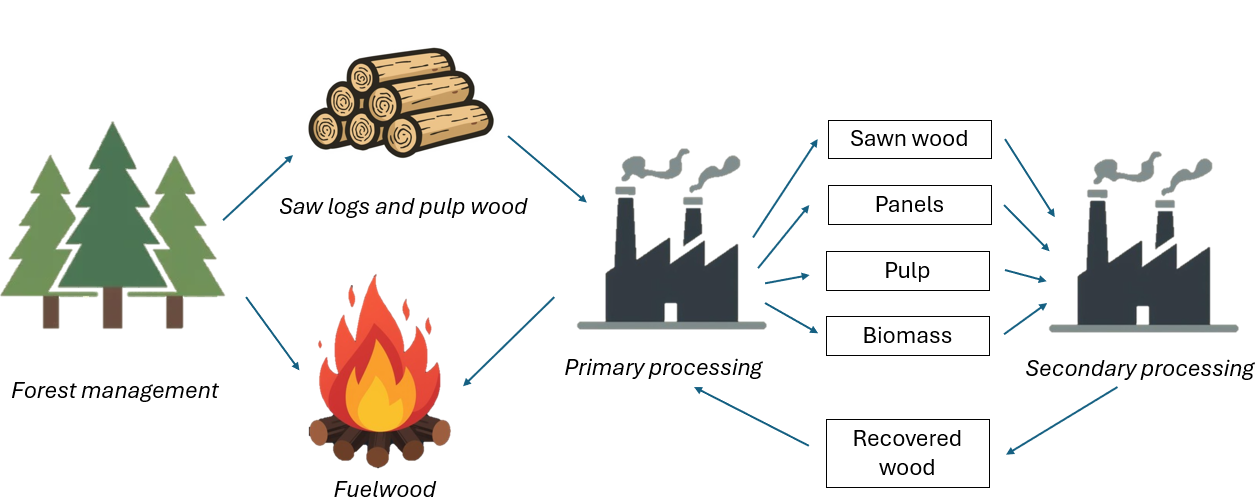

Figure 11-5: Schematic representation of the main stages and material flows in the forest-based sector. Fuelwood and industrial roundwood (saw logs, veneer logs, and pulpwood) enter the primary processing industries, producing sawn wood, panels, pulp, and biomass. These materials supply the secondary processing industries and manufacturing, which generate finished wood products. Some of these products (e.g., paper) are recovered and reintroduced into the production cycle. Adapted from WWF living forest report 2012 (https://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/living_forests_report_ch4_forest_products.pdf)

Wood resources can be further distinguished based on diameter, logs quality, and customer requirements:

Sawlogs

These are high-quality portions of the tree stem, typically straight, large in diameter, and free of defects such as knots, cracks, or curvature. Their uniform shape make them ideal for sawing into boards and beams.

Veneer logs

Veneer logs represent the top-quality class of roundwood. They are exceptionally straight, have fine and uniform texture, and contain no knots, rot, or visible defects. Because of their superior quality, they can be sliced or peeled into thin sheets (veneers).

Pulpwood

Pulpwood includes smaller-diameter logs and stems of lower quality than sawlogs or veneer logs. These logs may be slightly curved, knotty, or from fast-growing species with softer wood. Pulpwood often comes from thinnings, branches, or species not suitable for high-quality sawnwood production.

This classification usually takes place in the forest, where logs of similar assortments are piled together and then transported to primary processing industries (Figure 11-5), where they are transformed into semi-finished or finished products.

Sawlogs are processed in sawmills to produce sawnwood, such as boards and beams, which serve as the main raw material for timber construction and furniture. Modern sawmills use advanced machinery to maximize yield, but only about half of the incoming wood volume becomes sawnwood. The remaining fraction consists of residues such as bark, sawdust, and slabs, which are reused for energy and heat within the mill or sold to other industries (FAO, ITTO & UN, 2020; Bozzolan et al., 2024a). Veneer logs are peeled or sliced in specialized mills to obtain thin sheets of wood, which are glued together to form plywood and decorative panels, or used as surface layers. Veneer products are valued for their strength and appearance in furniture and interior design.

Pulpwood goes mainly to pulp and paper mills, where it is chipped and converted into pulp for paper, cardboard, and packaging. Advances in technology have improved both efficiency and environmental performance, while the increasing utilization of recycled paper has further reduced the sector’s raw material demand.. The paper industry remains one of the largest consumers of wood. Although digitalization has reduced demand for printing paper in recent years, the demand for packaging has increased (for more information see CEPI,2024).

Panel products are produced mainly from sawmill residues and a smaller share of low-quality logs (pulpwood). The panel industry manufactures plywood, particleboard, and fiberboard, which are widely used in furniture and construction sector. Because it relies on residues, this industry competes with the pulp and paper sector for raw material.

Finally, fuelwood is used for heat and energy, both in households and in biomass plants. Industrial wood residues and low-quality timber are often converted into pellets, briquettes, and other biofuels. Biomass energy remains extremely important in the EU and plays an increasing role in Europe’s transition toward renewable energy sources. In terms of overall use, about 52% of wood from primary and secondary sources is used for material production, while 48% is used for energy (Camia et al., 2018).

11.2.3 Timber flow: from the forest to primary processing

After harvesting, logs are usually sent to the closest processing facilities because transporting wood over long distances is expensive. However, high-quality logs are sometimes transported over greater distances to specialized mills that can process them more efficiently and maximize their value. In contrast, for some assortments such as fuelwood, processing takes place directly in the forest, where the wood is chipped on-site before being transported.

Where the timber goes depends on local industries, market prices and the decisions of forest owners. In general, logs are directed toward their highest-value end-use, as described in the previous paragraph. However, market conditions can alter this allocation: for instance, wood suitable for pulp or panels may instead be used for bioenergy if energy demand is high and prices are favorable.

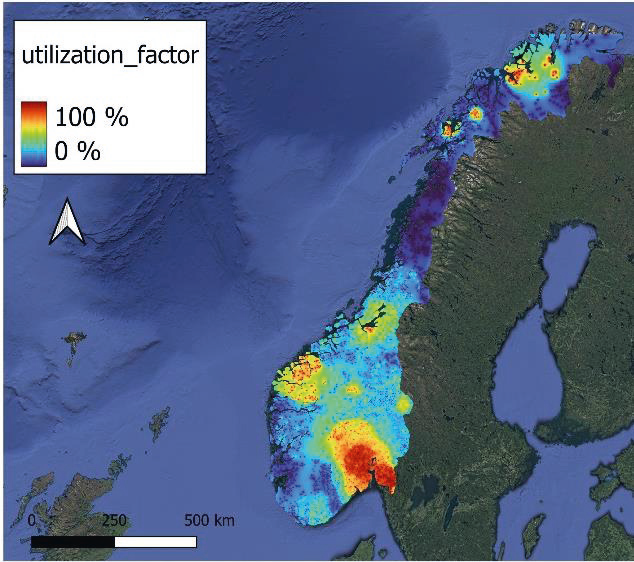

In regions where several industries rely on the same type of wood but resources are limited, competition for raw material becomes more intense. Figure 11-6 shows the results of a simulation conducted in southern Norway. The colored lines illustrate how timber flows from forest plots, where harvest is planned, to different industries, based on the available assortments (Bozzolan et al., 2024b).

Figure 11-6: Plot-to-Mill Allocation for Southern Norway. Left: Dots represent mills, with lines indicating potential flows of harvested wood from the forest. Right: Forecasted utilization of harvested wood. Red areas highlight regions with higher demand, where harvested wood is more likely to be absorbed by the wood industry (figure adapted from Bozzolan et al., 2024b)

Timber processing varies across Europe. In Northern and Central Europe, where coniferous forests dominate, sawmills and panel mills are the most important. In Southern Europe, with more mixed forests, traditional carpentry and small-scale processing are still common, although modern mills are growing. In forest-rich countries such as Germany, forest management and the wood industry are closely linked. Over time, they have optimized production together, leading to landscapes with large areas of straight-growing Norway spruce (Picea abies) suited to softwood sawmills.

|

Exercise: sourcing area for a saw mill |

|---|

|

The founders of a new saw mill are studying the required sourcing forest area. The capacity of the saw mill is 10.000 cubic metres of roundwood per year. Calculate the required sourcing forest area with following circumstances in mind:

The answer is 2380 ha. |

Avitabile, V., Camia, A., Mubareka, S., Alberdi, I., Hernández, L., Klatt, S., Gschwantner, T., Riedel, T., Lanz, A., Freudenschuß, A., Snorrason, A., Fischer, C., Castro Rego, F., Marin, G., Cañellas, I., Redmond, J., Fridman, J., Nunes, L., Rizzo, M., Bosela, M., Kucera, M., Notarangelo, M., Gasparini, P., Tomter, S. M., Wurpillot, S., Seben V., 2018. Mapping forest biomass available for wood supply in Europe. EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vol. 20, p. 8601

Bozzolan, N., Grassi, G., Mohren, F., & Nabuurs, G. J., 2024a. Options to improve the carbon balance of the harvested wood products sector in four EU countries. GCB Bioenergy, 16(1), e13104

Bozzolan, N., Mohren, F., Grassi, G., Schelhaas, M. J., Staritsky, I., Stern, T., Peltoniemi, M., Seben, V., Hassegawa, M., Verkerk, P.J., Patacca, M., Jansons, A., Jankovský, M., Palátová, P., Blauth, H., McInerney, D., Oldenburger, J., Jastad, E.O., Kubista, J., Antón-Fernández, C., Nabuurs, G. J. 2024b. Preliminary evidence of softwood shortage and hardwood availability in EU regions: A spatial analysis using the European Forest Industry Database. Forest Policy and Economics, 169, 103358

Camia, A., Robert, N., Jonsson, R., Pilli, R., García-Condado, S., López-Lozano, R., Velde, M. v. d., Ronzon, T., Gurría, P., M’barek, R., Tamosiunas, S., Fiore, G., Araujo, R., Hoepffner, N., Marelli, L., & Giuntoli, J., 2018. Biomass production, supply, uses and flows in the European Union : first results from an integrated assessment. Publications Office

CEPI Statistics, 2024. Key Statistics 2024: European pulp & paper industry report. Confederation of European Paper Industries, Brussels

FAOSTAT, 2025. Forestry Production and Trade. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FO

Forest Europe, 2020. The State of Europe’s Forests 2020. Forest Europe Liaison Unit, Bratislava

Gold, S., Korotkov, A., Sasse V., 2006. The development of European forest resources, 1950 to 2000. Forest Policy and Economics 8: 183–200

Henttonen, H.M., Nöjd, P., Mäkinen, H., 2024. Environment-induced growth changes in forests of Finland revisited – a follow-up using an extended data set from the 1960s to the 2020s. Forest Ecology and Management 559: 120799

Hetemäki, L., Kangas, J., Peltola, H. (Eds.), 2022. Forest Bioeconomy and Climate Change (Managing Forest Ecosystems, Vol. 42). Cham, Switzerland: Springer

Korhonen, K. T., Räty, M., Haakana, H., Heikkinen, J., Hotanen, J.-P., Kuronen, M., Pitkänen, J., 2024. Forests of Finland 2019-2023 and their development 1921-2023. Silva Fennica, 58(5): 24045

Lerink, B., Schelhaas, M-J., Schreiber, R., Aurenhammer, P., Kies, U., Vuillermoz, M., Ruch, P., Pupin, C., Kitching, A., Kerr, G., Sing, L., Calvert, A., Ní Dhubháin, A., Nieuwenhuis, M., Vayreda, J., Reumerman, P., Gustavsson, G., Jakobsson, R., Little, D., Thivolle-Cazat, A., Orazio, C., Nabuurs, G.J., 2023. How much wood can we expect from European forests in the near future? Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research, 96(4), 434-447

Mubareka, S. B., Renner, A., Acosta Naranjo, R., Armada Bras, T., Barredo Cano, J. I., Blujdea, V. N. B., Borriello, A., Borzacchiello, M. T., Briem, K., Camia, A., Canova, M., Cazzaniga, N. E., Ceccherini, G., Ceddia, M., Cerrani, I., Chiti, T., Colditz, R., De Jong, B., De Laurentiis, V., Egea González, F. J., Ferrario, V., Fuhrmann, M., García Casañas, C., Garcia Herrero, L., Gautron, S., Gras, M., Guillen, J., Gurría, P., Hekim, Z., Jonsson, R., Joosten, H., Korosuo, A., Kovacic, Z., La Notte, A., Labonté, C., Lasarte Lopez, J., Lehtonen, A., Lugato, E., M’barek, R., Macias Moy, D., Magnolfi, V., Mansuy, N., Merkel, G., Migliavacca, M., Morel, J., Motola, V., Omma, E. M., Orza, V., Paracchini, M. L., Patani, S., Perugini, L., Pilli, R., Piroddi, C., Rebours, C., Rey, A., Rossi, M., Rougieux, P., Sanchez Lopez, J., Scarlat, N., Schleker, T., Serpetti, N., Tandetzki, J., Tardy Martorell, M., Thomas, J. B., Trombetti, M., Tuomisto, H. L., Velasco Gómez, M., Virtanen, J., Völker, T., Yáñez Serrano, P., Zepharovich, E., & Zulian, G., 2025. EU biomass supply, uses, governance and regenerative actions (10-year anniversary edition). Publications Office of the European Union

Nabuurs, G.J., Van der Werf, D.C., Heidema, N., Van der Wyngaert, I.J.J., 2007. Ch 13. Towards a High Resolution Forest Carbon Balance for Europe Based on Inventory Data. In Freer Smith et al. (Eds). Forestry and Climate Change. OECD Conference, Wilton Park, 105-111

Nabuurs, G.J., Lindner, M., Verkerk, P.J., Gunia, K., Deda, P., Michalak, R., & Grassi, G., 2013. First signs of carbon sink saturation in European forest biomass. Nature Climate Change, 3, 792-796

Pretzsch, H., del Río, M., Arcangeli, C., Bielak, K., Dudzińska, M., Forrester, D. I., Klädtke, J., Kohnle, U., Ledermann, T., Matthews, R., Nagel, J., Nagel, R., Ningre, F., Nord-Larsen, T., & Biber, P., 2023. Forest growth in Europe shows diverging large regional trends. Scientific Reports, 13, 15373

Pucher, A., Erber, G., Hasenauer H., 2023. Europe’s potential wood supply by harvesting system. Forests 14(2): 398

Schelhaas, M.-J., Hengeveld, G., Filipek, S., König, L., Lerink, B., Staritsky, I., de Jong, A., & Nabuurs, G.-J., 2022. EFISCEN-Space 1.0 model documentation and manual (Report / Wageningen Environmental Research; No. 3220). Wageningen Environmental Research

FAO, ITTO, UN, 2020. Forest product conversion factors. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

UNECE, 2025. Joint Forest Sector Questionnaire definitions 2024 (English). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Geneva

Verkerk, P.J., Hassegawa, M., van Brusselen, J., Cramm, M., Chen, X., Imparato Maximo, Y., Koç, M., Lovrić, M., & Tekle Tegegne, Y., 2021. Forest products in the global bioeconomy. FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, on behalf of the Advisory Committee on Sustainable Forest-based Industries (ACSFI)

Glossary 11

|

Afforestation |

Planting trees on land that did not have forest before. |

|

Age class |

A group of trees of similar age in a forest. |

|

Carbon sink |

Something (e.g. a forest) that absorbs more carbon than it releases. |

|

Fellings |

Trees that are cut down. |

|

Forest Available for Wood Supply (FAWS) |

Forest area where wood can legally and practically be harvested. |

|

Forest restoration |

Helping degraded forests recover or replanting trees on degraded lands. |

|

Growing stock |

The total amount of wood in all living trees in a forest. |

|

Increment |

The yearly increase in the volume of wood in trees or forests. |

|

Natural disturbance |

Events like fires, storms, pests, or diseases that damage forests. |

|

Net annual increment (NAI) |

The increase in wood after accounting for trees that died or were harvested. |

|

Panel products |

Wood boards like plywood or particleboard, used in furniture and construction. |

|

Pulpwood |

Smaller or lower-quality logs used to make paper. |

|

Roundwood |

Tree stems that have been cut and prepared for use. |

|

Sawlog |

Large, straight logs used to make boards or beams. |

|

Sawmill |

Factory where logs are cut into lumber or boards. |

|

Sawnwood |

Timber that has been sawn into planks or boards. |

|

Stemwood |

The main trunk of a tree, used to measure how much usable wood it has. |

|

Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) |

Managing forests so they provide wood and other benefits now without harming their future health. |

|

Veneer log |

Very high-quality log used to make thin wood sheets (veneers). |

This Chapter is published on the EUROSILVICS platform, established as part of the EUROSILVICS Erasmus+ grant agreement No. 2022-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000086765.

Author affiliation:

|

Bas Lerink |

Wageningen Environmental Research, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, Netherlands |

|

Nicola Bozzolan |

European Forest Institute, Yliopistokatu 6B, 80100 Joensuu, Finland |