Chapter 54: Forest Conversion – Download PDF

Authors: Peter Spathelf, Guy Geudens, Anne Oosterbaan, Frits Mohren

Author affiliations are given at the end of the chapter

Intended learning level: Advanced chapter

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

|

Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

|

The chapter deals with the transformation of mostly single-species and homogeneous forests into structurally diverse and mixed forests for increasing climate resilience and adaptive capacity |

NOTE: this text is a complete draft, which will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

54.1 Introduction and Definitions 2

54.2 Forest conversion in the Netherlands and Flanders 3

54.3 State of forest conversion in Germany 4

54.4 Strategies for forest conversion and planning aspects 5

54.5 Economics and forest conversion 7

54.6 Forest conversion and Adaptive Forest Management 8

54.1 Introduction and Definitions

In forest conversion, stocks that are not functioning in the desired way are dramatically changed to a different tree species composition, age structure or management form. Depending on the social and geographic context, forest conversion can aim at significant changes of the forest. The English term ‘conversion’ is used worldwide for the conversion of primary forest to tree plantations or agricultural use (FAO 2007). In a European forestry context, ‘conversion’ has often been used to refer to conversion to a more profitable silvicultural system, such as changing from coppice to high forest, conversion from structure-rich mixed forest based on native species to homogeneous forest of productive exotics, or the reverse. Conversion differs from regular forest rejuvenation in that the intended generational change in rejuvenation should lead to a different type of forest compared to the current forest to be rejuvenated.

Ecological forest conversion in Germany has been underway for around 40 years and began even before the accelerated environmental change. The aim was and is to establish mixed forests with high structural diversity to promote forest stability. In the Netherlands and Flanders, until the 1950s the term ‘forest transformation’ referred to the planting of high-yielding species such as Douglas fir, larch and poplar in existing coppice or middle woodland, which was then further treated as high forest. Nowadays, the term is mainly used in a context of gradual development from homogeneous even-aged tallwood (monocultures) to structure-rich and mixed stocks. Conversion differs from regular forest rejuvenation in that the intended generational change in rejuvenation should lead to a different type of forest compared to the current forest to be rejuvenated.

Forest conversion encompasses a range of measures aimed at achieving an optimally structured, sustainably functional state of forests used by humans (Thomasius, 1996). Recently, the international term ‘restoration’ (i.e. restoration, renaturalisation) has also been used in this context (Wissenschaftlicher Beirat für Waldpolitik, 2021). Forest conversion is now an objective and funding element of almost all forestry strategies at federal and state level (UBA, 2019, DAS Indicator Report). As forest conversion is a relevant and urgent activity to increase the resistance and resilience of forests after degradation or disturbance, it is seen also as an upcoming field of forest restoration in Central Europe (Spathelf et al., 2018). Active forest conversion with the integration of adaptable tree species and tree removal to reduce competition shorten the development of succession towards climate-resilient forests and stabilise forests (see detailed discussion of the issue of non-management in Jandl et al., 2019).

For forest conversion, natural processes such as disturbances can be utilised. Windthrow creates openings in the homogeneous upper layer, after which spontaneous rejuvenation occurs and the ground vegetation and humus profile develop further. Since forest conversion, by definition, involves a drastic change in tree species composition and forest structure, management interventions that accelerate or guide natural processes are usually required. A well-planned combination of such measures is often necessary.

A central question for forest conversion is in which direction forests that are centuries-old cultural landscapes can be developed, i.e. which reference state should ultimately be aimed for in the transformation of the forests. Is this a forest that consists exclusively of native tree species and is therefore 100 % natural? Or can non-native tree species also be included? The decisive factor influencing the resilience of forest ecosystems is functional rather than native tree species diversity (Messier et al., 2019; Bauhus et al., 2017).

54.2 Forest conversion in the Netherlands and Flanders

Forest conversion in Flanders and the Netherlands mainly concerns the conversion of homogeneous, uniform or non-native plantations into more varied forests with a predominantly native tree species composition. The envisaged structural variation includes both a vertical stratification and a horizontal mosaic of development stages. An important note is that the objective, the forest to which we want to transform, is rarely precisely defined by managers in terms of desired site characteristics. Part of the explanation for this is that well-developed, old natural forests are lacking in Flanders and the Netherlands. For reference images, we rely on the surrounding countries and on hypotheses and model simulations. However, undesirable site characteristics (exotics, lack of structural variation, overly uniform timber assortments) can be interpreted precisely and the motivation to change them is often high.

Figure 54-1: Homogeneous low quality even-aged pine stand in Flanders (source ????).

The current forest scene in Flanders and the Netherlands is dominated by relatively young forests of Scots pine on the sandy soils and poplar in the valleys and polders, which until the second half of the last century were managed in large monocultures through a clearcutting system with relatively short rotations (15-30 years for poplar, 40-50 years for pine, see Figure 54-1). In Flanders, Corsican pine is the second most dominant conifer species on sandy soils; while in the Netherlands Douglas fir and larch are the most common. The stands with Corsican pine were generally only treated via low thinning, while in Douglas fir stands high thinning has also been applied in recent decades. As less and less regeneration is done via clearcutting, there is now only a limited area of young stands of these species, while the bulk of plantations of these species is over 40 years old (source ????).

54.3 State of forest conversion in Germany

Germany’s forests have undergone several phases of transformation over the past centuries. Deciduous forests were converted into homogeneous young coniferous forests, often consisting of spruce or pine. The hardwood/conifer ratio of 70/30 % around 1300 was ‘turned round’ to 30/70 % in 1913 (Johann et al., 2004). For several decades, especially in public forests, an (ecological) forest conversion has been taking place in the opposite direction: the monotonous, non-natural coniferous forests are being developed into diversely structured mixed forests with high ecological quality and stability (Fritz, 2006). The proportion of hardwood increased from 34 % in 1990 to 47 % in 2022 (BMEL, 2024). Large interdisciplinary research projects were carried out on ecological, economic and technical issues of forest conversion (BMBF focus on ‘Future-oriented forest management’, 1998-2004), which were reflected in numerous publications (e.g. MLUV, 2005; Spiecker et al., 2004).

Since the early 1990s, the federal government has been working with the federal states to promote forest restructuring measures, mainly via the joint task ‘Improvement of agricultural structures and coastal protection (GAK)’. In the period between 2000 and 2017, the federal states invested between 38 and 61 million euros annually in forest restructuring. These are normal budget funds in the state forests as well as subsidies for private forests (UBA, 2019).

The current status (November 2021) of forest conversion in Germany can be summarized as follows (from the document on the Forest Strategy 2050 [BMEL, 2021], UBA monitoring report on climate change [UBA, 2019] and BWI 3 [BMEL, 2024]):

• Around 80 % of German forests are mixed forests with two or more tree species, and the trend is continuing to rise slightly.

• The proportion of deciduous trees has increased, whereas the proportion of pure spruce and pine stands decreased between 2012 and 2022. Especially Norway spruce has lost 17 % of its area due to the consecutive drought years after 2018.

• The ratio of conifers to deciduous trees is currently 53:47.

• The average age of the German forest is 82 years; around 30 % of the forest is over 100 years old and 90 % of the younger forests (up to 20 years old) are the result of natural regeneration.

• Forest regeneration is most advanced in the state and corporate forests compared to private forests.

A recent evaluation report on the status and success of forest conversion in Brandenburg revealed deficits in the conversion of pure pine stands, particularly on very poor sandy sites, as well as problems with the cultivation of sessile oaks. According to the authors, the silvicultural possibilities for conversion are not being fully utilised, for example there is no concept for dealing with the American black cherry (Stähr et al., 2021).

Accelerated climate change and the current drought damage are leading to a reconsideration of the risk, particularly in the area of

- unstable spruce stands at altitudes below 600 m, and

- unstable beech stands with low localised water availability.

According to calculations by the Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems, there are around 2.2 million hectares of spruce forests and 620,000 hectares of beech forests that urgently need to be converted in Germany, plus around 400,000 hectares of damaged areas that are currently awaiting reforestation (Bolte et al., 2021). In order to manage this by around 2050, almost 100,000 ha of forest would have to be adapted each year. For spruce, these are the lower and middle elevations of the low mountain ranges, for beech mainly calcareous low mountain ranges but also lowland locations. According to the UBA monitoring report, around 22,000 hectares of forest were converted annually in Germany between 2000 and 2017 (across all forest ownership types) (UBA, 2019).

This means that ecological forest conversion must be significantly accelerated in the coming years. However, the temporary end of the conversion of the remaining pure stands does not mark the end of the ongoing need to adapt forest management to climate change.

54.4 Strategies for forest conversion and planning aspects

Conversion management comes into play when the current stock characteristics no longer meet the manager’s expectations or wishes. This may include, for example, a lack of stability or inadequate social services. Stability problems occur, for example, after heavy storm or snow damage, forest mortality due to air pollution or diseases and pests. Service provision may be inadequate due to insufficient productivity (quantity or quality), e.g. in coppice and medium wood in the absence of demand for firewood. Because of the increased demand for nature conservation and amenity value, many homogeneous, even-aged forests function inadequately and therefore become the subject of a conversion plan (Lust 1988).

A conversion plan is developed in three essential steps: a thorough diagnosis of the current state, a target description of the desired state and a concretisation of the procedure to be followed. During the diagnosis, both the growth location and the stand structure are analysed. This provides an indication of the need for conversion. The conversion objectives are first formulated generally for the forest complex and in a second phase for each stand. In a conversion plan, the choice of conversion objectives is made for each stand.

In establishing operational management guidelines for a conversion management of even-aged homogeneous stands, the following problems emerge (Hanewinkel, 1996):

• There are no clear target parameters for the desired structure of forests and stands after conversion. The ideal references used (e.g. compound coppice forest, old-growth forest, plenter forest) are difficult or impossible to translate into the initial situations during conversion.

• The results of the conversion (e.g. wood sorting, risks) can modelled but cannot be precisely foreseen.

• There is limited knowledge about the responsiveness of trees and stands to changing treatment methods (target diameter thinning, relying in main on natural rejuvenation, mixed stands).

• It is impossible to estimate the duration of the conversion period for a concrete stand.

In conversion, a distinction can be made between young and old stands. When young stands are converted, the focus will generally remain on the development of a limited number of stable future trees, just as if no conversion were carried out (unless, of course, a complete change in species composition is desirable).

A main line in the conversion of older stands is to reduce the standing timber stock or the basal area of trees in the upper storey. This also constitutes the essence of the conversion from even-aged to uneven-aged high forests, where the basal area of the upper storey is brought down to 10-15 m2 ha-1 (de Turckheim & Bruciamacchie, 2005).

As an illustration, we present here two conversion strategies. The usual management of homogeneous Norway spruce stands in southern Germany consists of a high thinning around 300 future trees per ha and a clearcut after 100-120 years. To transform such stands into more mixed and structured forest, Hanewinkel (2001) suggested as a guideline that up to a life time of 75 years, thinning should target no more than 150 future trees per ha. In older stands, a target diameter thinning follows (> 45 cm). In addition, between the stand age of 45 and 85 years, five groups are felled per hectare with a diameter of 30 m and these are planted with beech. The management costs increase by 1 to 13% during the conversion period compared to the management costs of a continued same-year forest operation with Norway spruce only.

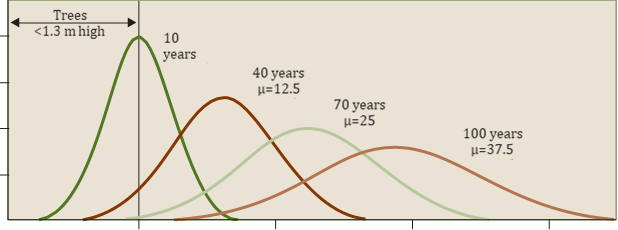

For converting uniform, homogeneous, even-aged oak forests in the Ozark Highlands of Missouri (USA) to uneven-aged stands, Loewenstein (2005) formulated the simple 3-2-1 rule. Here, no change in tree species composition is sought, but the transformation is aimed at obtaining an uneven-aged stand structure. The starting situation is an even-aged oak stand with full stocking. Here, the trees in the upper storey do not experience substantial competition from each other, but the growth area is still fully utilised. For mid-US oak stands, this corresponds to 60% of the maximum attainable ground surface at a given stem number. The latter is observed in unthinned stands in which trees spontaneously die due to competition among themselves (Gingrich, 1967). The most important measure in Loewenstein’s (2005) method is the thorough reduction of the growth space occupied by the upper storey to 3/6 of full stocking. This is done during strong thinning at intervals. The lower storey is also periodically reduced to below an occupied growth space of 2/6, leaving 1/6 available for the establishment of a subsequent cohort of rejuvenation for several years after each intervention. After a few thinning intervals, this creates an uneven-aged stand (Fig 54-2).

Figure 54-2: Theoretical diameter distributions of successive rejuvenation waves (with μ = mean diameter and σ = standard deviation from the cohort mean) when applying the 3-2-1 rule with a strong thinning cap every 30 years. After Loewenstein (2005).

54.5 Economics and forest conversion

Forest conversion and adaptation of forests to climate change have various economic facets:

- On the one hand, the isolated expenses for forest conversion (e.g. for preliminary cultivation to diversify the stocking composition) or the reduced yields caused by the conversion can be considered.

- However, it is more informative to compare the possible economic advantages of Continuous-cover forestry (CCF) initiated by forest conversion with those of age-class management.

- A forced change in the stocking of mixed coniferous forests to e.g. deciduous forests with thermophilic oaks in the coming decades can also have a considerable impact on the yield capacity of the forests.

The result of such calculations can vary greatly depending on whether or not cash flows (income and expenditure) are made comparable through discounting using financial mathematics or whether or not risk considerations are taken into account in management.

Regarding 1) The expenses for pre-planting vary depending on the intensity (how much area of a stand is converted?) and tree species as well as the cost rates for material and labour costs; an example with calculation aids can be found in Schölch (2009). The conversion of even-aged stands into uneven-aged stands can be achieved by early, even before the economic harvesting period.

Regarding 2) One of the decisive economic advantages of Continuous-cover forests compared to age-class forests, in which all trees are harvested within a short period of time, is the possibility of harvesting the trees individually according to their maturity and thus at the time of their maximum value growth. Trees that are cleared early have longer crowns and therefore better stability properties than relatively dense mature trees in the age-class forest. This enables harvesting in an optimal time window with good market conditions and reduces premature damage to the timber. In addition, the increased utilisation of natural processes in the structured permanent forest reduces forest maintenance costs.

When working with discounted payment differences (so-called ‘net present value’), a further advantage of CCF can be demonstrated. An early conversion of an even-aged pure stand into a structured and diverse (uneven-aged) forest through the removal of strong trees generates more income than the final utilisation of an age-class forest every 40 or 60 years, as Knoke (2009) explains. The uneven-aged CCF forest leads to more frequent and lower revenues, the age-class forest to rarer but higher revenues – if this is made comparable in financial mathematics through discounting, the Continuous-cover forest performs better. In addition, natural regeneration in Continuous-cover forests is generally more cost-effective than in age-class forests (Reiterer & Berner, 2017). This is also shown by studies from Scandinavia (Tahvonen & Rämö, 2016). Nevertheless, CCF management with less concentrated felling also has disadvantages compared to age-class forests, e.g. higher timber harvesting costs.

Although suitable operational comparisons are rare, it can be deduced from these basic considerations that a conversion to Continuous-cover forests has financial advantages over the management of age-class forest. And this analysis does not yet take into account the higher risk (storm, biotic damage) of age-class management. The results of comparative studies also vary depending on the assumed interest rate. The lower the interest rate, the closer Continuous-cover forest comes to age-class forest in terms of economic advantage, as the payment amounts received earlier in Continuous-cover forests no longer represent an advantage (effect of discounting no longer applies) (Knoke, 2009).

54.6 Forest conversion and Adaptive Forest Management

Ecological forest conversion is currently taking place in many forests in Germany. Particularly in state and community forests, where forest conversion began around 40 years ago, the remaining pure spruce and pine stands will have been converted by around 2030-40 (e.g. BaySf, 2020). However, forest conversion and adaptation to climate change are a permanent task. It cannot be assumed that a specific target forest with climax tree species, should it ever be achieved, will be permanently resistant and resilient to environmental changes. Particularly vulnerable forest areas that could be severely damaged due to climate change and increasing extreme climatic events must be identified in good time using suitable monitoring systems and then stabilised. Forest conversion and adaptation to climate change will therefore become a continuous challenge. This requires a suitable management approach – adaptive forest management (afm) – and ‘robust’ decisions that take increasing uncertainty into account.

In a European forestry context, ‘conversion’ is aiming at a significant change in forest composition and structure, such as from coppice to high-forest systems, or from homogeneous forests of productive tree species (inclusive exotics) to structure-rich mixed forest based on native species, or the reverse. Conversion also often refers to a more profitable silvicultural system for the forest owner. Thus, conversion is more than regular forest rejuvenation, it is an important field of activity in anticipating environmental change by enhancing the forests adaptive capacity.

Bauhus, J., Forrester, D. L., Pretzsch, H. et al. (2017). Silvicultural Options for Mixed-Species Stands. In: Pretzsch, H., Forrester, D. I. & Bauhus, J. (Eds.). Mixed-Species Forests. Ecology and Management. Springer Dordrecht. 433-501.

BaySf (2020). Klimawald 2.0. Das Magazin der Bayerischen Staatsforsten. 70 S. https://www.baysf.de/de/multimedia-story/klimawald.html.

BMEL (Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft) (2021). Waldstrategie 2050. Nachhaltige Waldbewirtschaftung – Herausforderungen und Chancen für Mensch, Natur und Klima. https://www.bmel.de/DE/themen/wald/waldstrategie2050.html.

BMEL (Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft) (2024). Der Wald in Deutschland. Ausgewählte Ergebnisse der vierten Bundeswaldinventur. https://www.bundeswaldinventur.de/fileadmin/Projekte/2024/bundeswaldinventur/Downloads/BWI-2022_Broschuere_bf-neu_01.pdf

Bolte, A., Höhl, M., Hennig, P. et al. (2021). Zukunftsaufgabe Waldanpassung. AFZ-DerWald 4. 12-16.

Fritz, P. (Hrsg.) (2006). Ökologischer Waldumbau in Deutschland. Fragen, Antworten, Perspektiven. Oekom-Verlag. 352 S.

Jandl, R., Spathelf, P., Bolte, A. et al. (2019). Forest adaptation to climate change – is non-management an option? Annals of Forest Science, SI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0827-x

Johann, E., Agnoletti, Axelsson, A.-L. et al. (2004). History of Secondary Norway Spruce Forests in Europe. In Spiecker, H. et al. (Eds.). Norway spruce conversion—options and consequences. European Forest Institute Research Report 18. Brill, Leiden. 25-62.

Knoke, T. (2009). Zur finanziellen Attraktivität von Dauerwaldwirtschaft und Überführung: eine Literaturanalyse. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 160. 152-161.

Messier, C., Bauhus, J., Doyon, F. et al. (2019). The functional complex network approach to foster forest resilience to global changes. Forest Ecosystems 6/21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-019-0166-2.

MLUV (Ministerium für Landwirtschaft, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz des Landes Brandenburg) (2005). Ökologischer Waldumbau im nordostdeutschen Tiefland. Eberswalder Forstliche Schriftenreihe Band XXIII. BMBF-Forschungsverbund ‚Zukunftsorientierte Waldwirtschaft‘. 141 S.

Reiterer, F. & Berner, C. (2017). Dauer- versus Altersklassenwald. Forstzeitung 1. 11-13.

Schölch, M. (2009). der Vorbau als schneller Weg zum Waldumbau in Fichtenbeständen. LWF Wissen

Spathelf, P., Stanturf, J., Kleine, M., Jandl, R., Chiatante, D., Bolte, A. (2018). Adaptive Measures: Integrating Adaptive Forest Management and Forest Landscape Restoration. Ann. For. Sci 75. Published online: May 7, 2018; https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-018-0736-4.

Spiecker, H., Hansen, J., Klimo, E. et al. (2004). Norway spruce conversion—options and consequences. European Forest Institute Research Report 18. Brill, Leiden. 269 pp.

Stähr, F., Degenhardt, A. & Rose, B. (2021). Evaluierung des Waldumbaus im Land Brandenburg. Analyse zum Stand und Erfolg des Waldumbaus im Gesamtwald des Landes Brandenburg. In MLUK, LFE, Abschlussbericht. 90 S.

Tahvonen, O. & Rämö, J. (2016). Optimality of continuous cover vs. clear-cut regimes in managing forest resources. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 46. 891-901.

Thomasius, H. (1996). Geschichte, Anliegen und Wege des Waldumbaus in Sachsen. Schriftenreihe der Sächsischen Landesanstalt für Forsten 6. 11-52.

UBA (Umweltbundesamt) (2019). Monitoringbericht 2019 zur Deutschen Anpassungsstrategie an den Klimawandel. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/das_monitoringbericht_2019_barrierefrei.pdf.

Wissenschaftlicher Beirat für Waldpolitik (2021). Die Anpassung von Wäldern und Waldwirtschaft an den Klimawandel. Berlin. 192 S.

Peter Spathelf, HNE Eberswalde, Schicklerstrasse 5, 16225 Eberswalde, Germany

This Chapter is published on the EUROSILVICS platform, established as part of the EUROSILVICS Erasmus+ grant agreement No. 2022-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000086765.

Author affiliation:

|

Prof. Dr. Spathelf, Peter |

HNE Eberswalde |

|

Geudens, Guy |

|

|

Oosterbaan, Anne |

|

|

Mohren, Frits |