Chapter 40: Tree species selection – Download PDF

Authors: Peter Spathelf, Bruno De Vos, Bart Muys, Frits Mohren

Author affiliations are given at the end of the chapter

Intended learning level: Advanced

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

|

Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

|

In the following chapter the fundamentals of tree species selection are described with a special emphasis on site conditions. Moreover, relevant technical and economic aspects are discussed. |

NOTE: this text is a complete draft, which will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

40.2 Species selection based on site characteristics (ecological site classification systems) 3

40.2.3 Other environmental factors 4

40.5 Effects of tree species and provenance selection on the ecosystem 6

40.6 Site suitability assessment 7

40.7 Species selection based on management objectives 7

40.8 Technical and economic considerations 9

40: Tree species selection

Tree species selection involves choosing tree species for afforestation and reforestation on a given site, primarily guided by an ecologically based framework. This choice is especially important in the establishment of new forests and to a lesser extent in reforestation, as in the latter case, an estimation can already be made based on the existing tree species. However, in both situations, careful consideration needs to be given to which species are best adapted to the site, suitable for achieving the forest management objectives, and feasible in terms of technical and economic aspects of regeneration. Moreover, there are cases where deliberate interventions are necessary to modify the existing species composition and achieve a more desirable mix of tree species. In such transformations (often termed as forest conversion, see chapter 54), the selection of tree species becomes a crucial aspect to address.

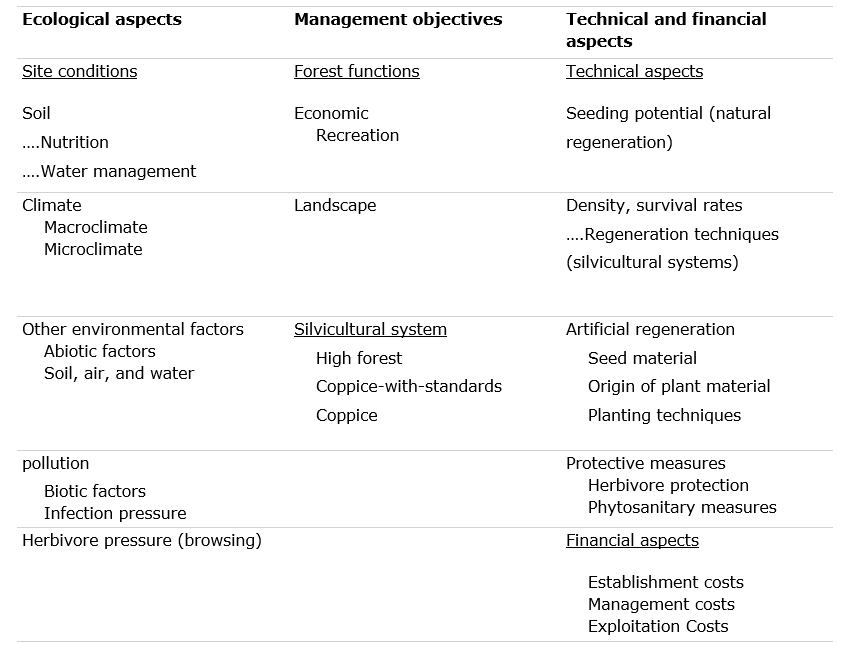

In classic forestry literature (e.g., Van Miegroet, 1976, Röhrig et al., 2006), tree species selection is described as the most critical decision made in forest management. It is a multi-criteria problem with numerous uncertainties. To solve such an issue, priority must be given to the criteria that are most quantifiable and least variable over time. Therefore, the first step in tree species selection is an analysis of the site conditions (climate, soil, and other environmental factors), based on which potential suitable tree species can be selected from the regionally available species pool. This species pool consists of all species that can, in principle, grow in a particular region, including non-native tree species. Species are suitable for a given site when they show good growth and vitality there, as well as low risk. Furthermore, considerations arising from management objectives and a range of technical and economic feasibility factors will also influence the final species selection. This chapter discusses the aforementioned aspects in more detail. A summary of these aspects can be found in Table 40-1.

Table 40-1: Schematic representation of the successive steps in tree species selection, with the respective assessment criteria.

40.2 Species selection based on site characteristics (ecological site classification systems)

The occurrence of species is primarily determined by site factors. Thus, species selection is relies on knowledge of the autecology of tree species. It can be determined which species can potentially thrive at a particular site. In Flanders and the Netherlands, but also in Germany, soil factors (physical and chemical soil quality, water management) are considered more important than climatic factors, which vary only to a limited extent due to the small variation in altitude and latitude. Additionally, local environmental factors, such as soil and air pollution, may also be relevant.

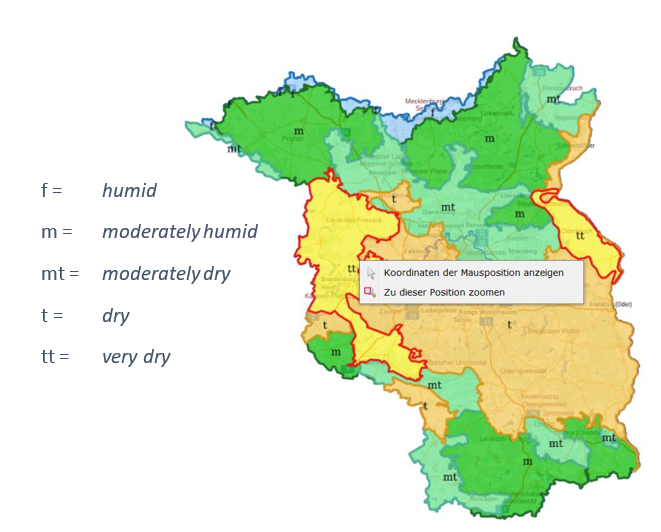

Since several decades, a variety of classification systems to describe site differences have been developed in Europe. In general, ecological site classifications in forestry consist at two levels: a regional (large-scale) level with driving factors such as precipitation and/or altitude, and a local level based on the site unit (normally expressed in nutrition status and water supply of the site). See as an example the site classification system of the German federal state of Brandenburg, with five distinct regions in terms of rainfall and five general site units with respect to nutrition (Riek et al., 2015).

Macroclimatic factors can be very variable when there is topographic change (as in alpine regions) or show little variation such as in Northern Germany or in Flanders and the Netherlands and therefore play a subordinate role, as long as the selection remains limited to species from our climatic region. Only higher and more inland areas, such as the Austrian Alps, German middle mountainous regions or the Drents plateau in Northeast Netherlands, have a different climate with lower average temperatures and higher annual rainfall. For example, the colder and wetter conditions in Drenthe make Norway spruce clearly better suited to grow there than in lower or more southern areas. As a result of climate change, there may be a certain shift in the distribution ranges of species in the future.

However, microclimate does play a role in tree species selection. First and foremost, consideration must be given to the exposure of the site. In areas with high wind speeds, species like sweet cherry, silver birch, and Norway maple are not suitable, but aspen, hornbeam, blackthorn, and hawthorn are. In locations where frost can occur, which is the case almost everywhere in Central Europe, a species must have sufficient winter hardiness to avoid frost damage. Planting species sensitive to night-time frost, such as walnut, Japanese larch, and sweet chestnut, should be avoided in strongly exposed sites or in valleys where cold air can accumulate. In addition to temperature and wind, humidity also plays a role for some species: some prefer high humidity, such as Norway spruce, silver fir, Norway maple, black alder, and wych elm, while sweet chestnut, Corsican pine, and red oak perform better in low humidity conditions.

Figure 40-1: Ecological site classification system of the German federal state of Brandenburg. Source: https://www.brandenburg-forst.de/geoportal/

Soil properties play a decisive role in the choice of suitable tree species. When assessing soil suitability, especially the physical properties, chemical soil fertility, and moisture supply are essential.

Physical properties can be deduced from the description of the soil profile: texture, bulk density, organic matter content, and stoniness of the soil horizons provide information about the root zone and moisture reserves. Some tree species prefer deep, loamy, and moist soils, such as common ash with its taproot system. Beech, which also thrives on loamy soils but has a heart-shaped root system, roots superficially and is particularly sensitive to oxygen deficiency in the rhizosphere. Compacted soils or soils with stagnant groundwater are therefore unsuitable and can lead to windthrow in such species, significantly increasing operational risks.

Chemical soil fertility is largely derived from acidity, cation exchange capacity, and base saturation. Some tree species, such as common ash, do not tolerate acidic, base-poor soils, whereas beech can handle them but only grows optimally when there is lime in the subsoil. Species like Scots pine and silver birch have few demands on the soil’s nutrient status and can even grow on chemically poor soils. As moisture availability improves, other tree species also show good growth. However, when the soil becomes too wet due to a permanently high-water table, the choice of tree species is again limited to a small number of species, including black alder, silver and downy birch, white willow, and poplars.

40.2.3 Other environmental factors

In addition to climate and soil, various abiotic and biotic environmental factors can pose risks to the survival or successful development of certain tree species. Soil, water, and air pollution can significantly influence tree growth. For instance, afforestation of previously intensively farmed lands may strongly inhibit the growth of sensitive tree species like small-leaved lime and common ash due to soil contamination with atrazine (Vaes et al., 2001). Most tree species tolerate soils contaminated with heavy metals, but some, such as willows and poplars, preferentially absorb zinc and cadmium and release them into the environment through their leaf litter. Birch accumulates zinc but not cadmium. In the case of such contaminations, it is preferable to choose tree species that do not absorb and disseminate these metals, such as common ash (see, among others, Mertens et al. 2007).

An excess of nitrogen leads to imbalanced mineral nutrition, resulting in nutrient deficiencies and increased susceptibility to other infections, as seen in cases of watermark disease in white willow (De Vos et al. 2007). Additionally, it is suspected that high nitrogen load in forest ecosystems increases susceptibility to fungal infections, making the planting of many conifer species on nitrogen-rich agricultural lands very risky due to root rot. Furthermore, trees along the coast are exposed to high salt concentrations, limiting the choice of tree species. In low-lying areas along rivers, flood tolerance can be an important selective factor (see Glenz et al. 2006). Finally, biotic factors can also restrict tree species selection. The local presence of the elm bark beetle, which acts as a vector for Ophiostoma fungi (causing Dutch elm disease), makes elm a prohibited choice in many places. However, white elm (Ulmus laevis) appears to be less susceptible to infestations and might be planted under limited risk.

The provenance of tree seed or stock refers to its geographical origins. The natural migration speed of provenances and tree species is far too slow to keep pace with climate change. In order to support this migration of tree species, the concept of ‘assisted migration’ has been under discussion for several years (Williams & Dumroese 2013). This refers to the planned translocation of provenances, but also tree species, to an area with a suitable climate (save movement). The concept is controversial, as the principle of ‘local is best’ is generally followed when selecting tree species and provenances. It was previously assumed that locally or regionally sourced propagation material was best adapted to the respective growing location. This is certainly correct in retrospect, but does not necessarily apply to a future shaped by climate change. Assisted migration can not only ensure the productivity of forest ecosystems, but also introduce new genotypes into the gene pool of a population and thus contribute to a better adaptability of forests (‘insurance hypothesis’, Bauhus et al. 2017; Aitken et al. 2016). On the other hand, there is a risk of maladaptation or invasiveness, especially when species or provenances are transferred over long distances, if climate fit is not taken into account (Spathelf & Linde 2020; Messier et al. 2019).

Non-native tree species (other terms: Neophytes, non-native, alien, foreign or exotic tree species) are plant species that have arrived in a specific area after the year 1492 (discovery of America) with the direct or indirect involvement of humans and live there in the wild. Non-native species can spread in particular due to the removal of geographical (especially mountains), but also climatic, demographic or ecosystem barriers (BfN 2020; Spathelf & Linde 2020). Non-native tree species are described as invasive if they displace native tree species due to their competitive strength and thus spread uncontrollably.

Numerous tree species worldwide are not native to their current cultivation area. In the Iberian Peninsula, for example, short rotation eucalyptus stands have been established on large areas and in the UK, Sitka spruce has been successfully established. The plantation forest-like management of these exotic tree species in the western part of Europe also entered the literature as ‘Atlantic Forestry’ (Mason & Valinger, 2013). According to Otto (1994), non-native tree species are ecologically beneficial if they are suitable for the site, rejuvenate well, are easily mixed (but not invasive), are able to form vertical forest structures and are phytopathologically robust.

Non-native tree species have also been cultivated in Germany for over 100 years. In view of climate change, uncertainty remains in the future suitability assessment if conclusions are drawn from retrospective suitability parameters. Therefore, in addition to historical experience, climate similarity from analogous regions and cultivation experience from the area of origin are a necessary basis for assessing these tree species for the climate-resilient forest of the future.

When analysing the suitability of exotic tree species for north-eastern Germany, Lockow (2004) identified Douglas fir, Northern red oak, grand fir, Western red cedar and Japanese larch as well growing, robust and capable of regeneration – an assessment that is still valid today. Using a complex filter method (climate, utility and cultivation filter), Schmiedinger et al. (2009) screened climate-appropriate exotic tree species for Bavaria and identified, among others, grand fir, Northern red oak and Douglas fir as suitable (with sufficient cultivation experience), but also a number of other tree species for which no cultivation experience is yet available: Ponderosa pine, Macedonian pine, silver lime and Oriental beech.

40.5 Effects of tree species and provenance selection on the ecosystem

Not only do growth site conditions determine the choice of a suitable tree species or provenance, but the selected tree species (and provenances) themselves also have an impact on the further development of the growth site. Tree species with poorly degradable litter, such as beech, oak, sweet chestnut, larch, and Scots pine, typically lead to the formation of thick, slowly decomposing litter layers (moder and mor humus forms) and can degrade the soil. In terms of soil quality, priority can be given to tree species that are suitable for the growth site and preferably have rich and quickly decomposable litter, such as lime, ash, bird cherry, and maple (see Muys & Van Elegem, 1996; Hommel et al., 2007).

Furthermore, each species has a specific rooting pattern, allowing them to access water and nutrient reserves from different soil horizons. As the roots penetrate, the soil becomes physically accessible, and species-specific nutrient uptake patterns result in diverse element concentrations in leaves or needles, introducing nutrients into the cycle in varying ratios.

40.6 Site suitability assessment

Based on a comparison of site characteristics with the requirements of individual tree species, it can be determined which species may be suitable for afforestation or reforestation. Several methods and systems have been developed to assist managers in making the right choice. Ecograms provide a systematic overview of the degree of soil fertility or acidity and the level of moisture supply under which different tree species occur and/or exhibit good growth. Ecograms offer valuable insights into the relative position of trees along different environmental axes (Rogister, 1981; Ellenberg, 1996), but they do not provide a definitive quantitative measure for the suitability of a specific growing site.

Both in the Netherlands (Van Goor et al., 1974; Paasman, 1988) and in Belgium (Weissen, 1991; 1994), methodologies have been developed to establish a relationship between specific soil types and the growth expectations of tree species. With this approach, growth potential of different tree species can be predicted based on data from soil maps (or after on-site soil analysis). In Flanders, an expert system called BOBO was developed based on characteristics obtained from the Belgian soil map (mainly texture, moisture regime, and profile development). It indicates soil suitability for 35 tree species and numerous shrub species, each classified into five suitability classes (De Vos, 2000). This program can take either the soil type or the tree species as input and automatically selects suitable species or suitable soils, respectively. Besides the soil series, on-site soil characteristics can also be entered into BOBO, whereby suitability is adjusted favourably or unfavourably. Moreover, BOBO includes species-specific site requirements, indicators, and tolerance classes in descriptions per species. In the Netherlands, Stiboka (Foundation for Soil Mapping) has developed a valuation system for the suitability of soils for the growth of seven important tree species (Haans, 1979). Similar to the Flemish system, this system is based on the variation in soil types. The growth expectation is expressed as good, normal, or poor growth based on the drainage condition, moisture-retaining capacity, acidity, and nutrient status of the soil, depending on the mean annual increment that a tree species can achieve (de Bakker & Locher, 1990).

Other systems have been developed that use other, more indirect indicators of soil suitability. A notable example is the system devised by Claessens (2003) for Wallonia, which allows determining soil fertility and water supply, and subsequently potential suitable tree species, based on selected indicator species from the ground cover. However, such a system can only be used in existing forests with well-developed ground cover. In the Netherlands, Bannink et al. (1973) developed a similar system to predict the growth of Scots pine on sandy soils.

40.7 Species selection based on management objectives

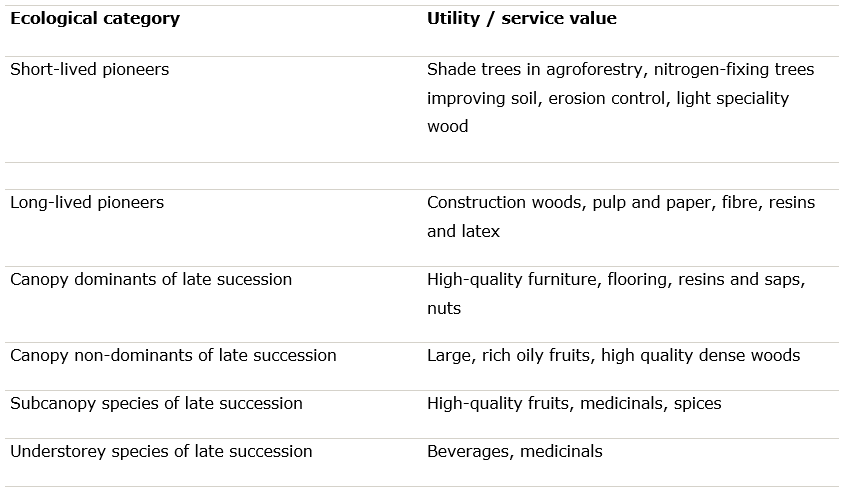

Once the ecological possibilities have been determined, a choice must be made based on the objectives of the forest plantation or regeneration. In many cases, the analysis of site suitability will result in a list of potential species for use, but the final selection must be made considering the specific products and services that the new forest is intended to provide (Table 40-2).

Table 40-2: Utility of species for different objectives acc. to Ashton & Kelty (2018).

If timber production is the primary objective, then in high forest systems, species will be selected primarily based on their ability to produce timber or veneer, such as beech, oak, ash, and Douglas fir, or fast-growing species that can produce large wood volumes in a relatively short period, such as poplar. Since the harvesting ages of most tree species in high forests are far in the future, it is not very meaningful to base species selection on the current timber market. Of much greater importance is ensuring sufficient vital and stable stands to minimize operational risk. For biomass cultivation in short rotation coppice, willow and poplar offer the most potential due to their regenerative capacity and rapid growth. Regenerative capacity is also an important selection criterion in traditional coppice systems.

For the establishment and regeneration of forests focused on aesthetic value, tree and shrub species can be chosen for recreational, landscape, or cultural reasons. Sweet chestnut and hazel provide desirable fruits, while maple species and red oak display beautiful autumn foliage and sweet cherry, wild apple, and pear have attractive spring blossoms, and the blossoms of lime species have a delightful fragrance. Thorny shrubs like hawthorn, blackthorn, and rose species can be planted in areas where no trampling is desired. Oaks and lime trees hold symbolic and cultural significance. When creating a forest for landscape purposes in the short term, pioneer species are often used in combination with slower-growing species that can form a second generation. Pioneer trees like silver and downy birch, common alder, willows, and poplars grow quickly, creating a forest microclimate within a decade and providing a suitable environment for subsequent generations with species like ash, oak, or beech. In places where nature development is the primary goal, spontaneous regeneration from existing populations is usually preferred. If planting is necessary, a combination of native species is often recommended. Where the protective function of the forest is most important, species selection is adapted to address specific issues. For mitigating visual disturbances and noise, evergreen species are most suitable, while species with an extensive, shallow root system are best suited for erosion control.

In Germany, there is a long history of developing so-called forest development types. These are species mixtures which were developed as recommendations for the respective site units. They consist of a leading tree species and a variety of more or less admixed tree species which can be seen as matching with the respective site unit. Examples: Oak-birch stands or European beech-conifer stands. The forest development types allow to optimise tree species selection (matching) in the regeneration phase of sustainable forest management and are valuable silvicultural tools in practical forestry, especially for the large state forest enterprises (Riek et al., 2015).

40.8 Technical and economic considerations

After determining the set of potential tree species to be planted or regenerated based on ecological possibilities and considering the management goals and functional requirements of the new forest, there are several technical and economic feasibility considerations that influence the final choice of species to be planted or regenerated. It is crucial to create conditions for successful regeneration. In areas with high browsing pressure, natural regeneration of broadleaf species will only be possible if resources are invested in effective game protection. If such resources are not available, the planting of non-preferred species such as some conifers or unpalatable species like birch may have some chance of success. The choice of regeneration system will also determine the possibilities for using certain species. For instance, in the case of conversion through clearcutting, regeneration of species sensitive to drought (such as beech) would face significant risks.

Furthermore, the regeneration must also be technically feasible: suitable seedlings or seeds of a suitable, either native or non-native origin must be available. In heavily overgrown situations, larger plant material must be used, which is, however, considerably more expensive than regular seedlings. Also, the potential need for later care of the regeneration to ensure the stand’s successful establishment must be taken into consideration. Once the choice of species for regeneration or planting has been made, a planting scheme can be developed. In the following chapters, the technical and ecological aspects of forest establishment and treatment will be further elaborated.

References

Aitken, S. N. & Bemmels, J. B. 2016. Time to get moving: assisted gene flow of forest trees. Evolutionary Applications 9(1). 271–290.

Ashton, M.S. & Kelty, M.J. 2018. The Practice of Silviculture. Applied Forest Ecology. John Wiley & Sons, 784 pp.

Bannink, J.F., H.N. Leijs & Zonneveld, I.S. 1973. Vegetatie, groeiplaats en boniteit in Nederlandse naaldhoutbossen . Wageningen, Pudoc, Verslagen van landbouwkundige onderzoekingen no. 800

Bauhus, J., Forrester, D.I. & H. Pretzsch 2017. From Observations to Evidence. About Effects of Mixed-Species Stands. In: Pretzsch, H., D.I. Forrester, J. Bauhus (Eds.): Mixed-Species Forests. Ecology and Management. Springer Dordrecht. 27-71.

Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN) 2020. https://neobiota.bfn.de/grundlagen/anzahl-gebietsfremder-arten.html

Claessens, H. 2003. Observer la végétation pour choisir une essence adaptée au milieu. Note Technique Forestière de Gembloux, no 9. Faculté Universitaire des Sciences Agronomiques, Gembloux.

De Bakker, H. & Locher, W.P. 1990. Bodemkunde van Nederland. Deel 2: Bodemgeografie. Malmberg, Den Bosch.

De Vos, B. 2000. BOBO versie 1.0 – Bodemgeschiktheid voor bomen. Computerprogramma. Instituut voor Bosbouw en Wildbeheer, Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, Geraardsbergen.

De Vos, B., Huvenne, Messens, H.E. & Maes, M. 2007. Nutritional imbalance caused by N excess is correlated with the occurrence of watermark disease in white willow. Plant and Soil 301: 215-232.

Ellenberg, H. 1996. Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen in ökologischer, dynamischer und historischer Sicht. Stuttgart, Ulmer verlag.

Glenz, C., Schlaepfer, R., Iorgulescu, I. & Kienast, F. 2006. Flooding tolerance of Central European tree and shrub species. Forest Ecology and Management 235: 1-13.

Haans J.C.F.M. 1979. De interpretatie van bodemkaarten. Rapport 1459, Stichting voor Bodemkartering, Wageningen.

Hommel, P., de Waal, R., Muys, B., J. den Ouden, J. & Spek, T. 2007. Terug naar het lindewoud: strooiselkwaliteit als basis voor ecologisch beheer. KNNV: Zeist, Nederland.

Lockow, K.-W. 2004. Ergebnisse der Anbauversuche mit amerikanischen und japanischen

Baumarten. In LFE (Landesforstanstalt Eberswalde) (Hrsg.): Ausländische Baumarten in Brandenburgs Wäldern. 41–101.

Mason, B. & Valinger, E. 2013. Managing forests to reduce staorm damage. In Gerdiner et al. (Eds.). Living with Storm Damage to Forests. EFI- What Science Can Tell Us 3. 87-96.

Mertens, J., L. Vannevel, A. De Schrijver, F. Piesschaert, A. Oosterbaan, F.M.G.Tack & Verheyen, K. 2007. Tree species effect on the redistribution of soil metals. Environmental Pollution 149: 173-181.

Muys, B. & van Elegem, B. 1996. Boomsoortenkeuze bij het bebossen van landbouwgronden. De Boskrant 26: 113-116.

Otto, H.-J. 1994. Waldökologie. Ulmer, Stuttgart. 391 S.

Paasman, J.M. 1988. Bosdoeltypen en de Groeiplaats. Directie Bos- en Landschapsbouw. Ministerie voor landbouw en visserij, Utrecht.

Riek, W., Russ, A. & Kühn, D. 2015. Waldbodenbericht Brandenburg. Zustand und Entwicklung der brandenburgischen Waldböden. Eberswalder Forstliche Schriftenreihe Band 60. 172 S.

Rogister, J. 1981. Het karakteriseren van bosplantengezelschappen met behulp van trofie- en hydrie-soortengroepen. Toepassing op gezelschappen op natte en vochtige groeiplaatsen. Proefstation Waters en Bossen, Groenendaal.

Röhrig, E., N. Bartsch & von Lüpke, B. 2006. Waldbau auf ökologischer Grundlage. Verlag Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart.

Schmiedinger, A., Bachmann, M., Kölling, C. et al. 2009. Gastbaumarten für Bayern gesucht. LWF aktuell 74. 47-51.

Spathelf, P. & Linde, A. 2020. Gebietsfremde Baumarten in unserem Wald – Chance oder Risiko? Jahrbuch Band II 2020 der Nationalparkstiftung Unteres Odertal. 8-17.

Van Goor, C.P., K.R. Van Lynden & van der Meiden, H.A. 1974. Bomen voor nieuwe bossen. tweede herziene druk van “Houtsoorten voor nieuwe bossen in Nederland”. Koninklijke Nederlandsche Heide Maatschappij, Arnhem.

Van Miegroet, M. 1976. Van bomen en bossen. 2 vols.. Story-Scientia, Gent.

Vaes, F. & Pans, K. 2001. Bosbouwpraktijk. Educatief Bosbouwcentrum Groenendaal. Afdeling Bos en Groen, Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, Brussel.

Weissen, F., P. Baix, J.P. Boseret, L. Bronchart, M. Lejeune, P. Maquet, D. Marchal, J.L. Marchal, J.L. Masson, F. Onclincx, P. Sandron, & Schmitz, L. 1991. Le fichier écologique des essences. 3 delen. Ministère de la Région Wallonne, Namen.

Weissen, F., L. Bronchart & Piret, A. 1994. Guide de boisement des stations forestières de la Wallonie. Ministère de la Région Wallonne, Namen.

Williams, M.I. & Dumroese, R.K. 2013. Preparing for climate change: forestry and assisted migration. J For 114: 287–297.

Peter Spathelf, HNE Eberswalde, Schicklerstrasse 5, 16225 Eberswalde, Germany

Acknowledgements

This Chapter is published on the EUROSILVICS platform, established as part of the EUROSILVICS Erasmus+ grant agreement No. 2022-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000086765.

Author affiliation:

|

Peter Spathelf |

Eberswalde University for Sustainable Development, Germany |

|

Bruno De Vos |

Research Institute for Nature and Forest, Belgium |

|

Bart Muys |

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium |

|

Frits Mohren |

Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands |