Chapter 44: Pruning – Download PDF

Authors: Patrick Jansen, Robbie Goris, Bart Muys, Peter Spathelf

Author affiliations are given at the end of the chapter

Intended learning level: Basic

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

|

Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

|

This chapter elaborates on branch development of trees and pruning (formative pruning and stem raising), especially for increasing the quality of timber produced. |

NOTE: this text is a complete draft, which will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

44.2 Branch and pruning biology 2

44.2.2 Branch attachment and wound responses 4

44: Pruning

Pruning involves the removal of branches from the trunk or crown of trees. It is commonly used in fruit cultivation to maximize flowering and fruit set, and in urban green management to develop well-formed, healthy crowns or provide unobstructed traffic flow. In forest management, pruning is employed to produce quality timber (Jansen et al., 2009). Successful pruning requires an understanding of branch anatomy and wound recovery physiology. The tree bark effectively shields the xylem tissue from infection by fungi, bacteria, and insects. Pruning locally breaches this protection, requiring prompt overgrowth of the resulting pruning wound to close the protective layer. After a general theoretical introduction to pruning biology, two types of pruning in forest management are discussed. In the young phase of a stand, formative pruning (also called training) can ensure the formation of continuous straight stems with minimal taper. Subsequently, in the thicket and pole stage, stem raising (also called stem pruning) can produce knot-free wood at the earliest possible. That section also delves into some technical and economic aspects of stem raising.

44.2 Branch and pruning biology

Before discussing the tree’s response to pruning, we first examine how trees naturally react to the shedding of dead branches.

When it comes to trees in a forest setting, the leaves or needles on the lower branches of trees become increasingly shaded due to stand closure, leading to a significant reduction in photosynthesis. Ultimately, the light level falls below the light compensation point (see Chapter 3), making maintenance costs higher than the returns from photosynthesis (Van Alphen, 1983). Consequently, the branch dies, and the tree is forming a protective layer between living and dead tissue. The dead branch is susceptible to fungi and insects, and if weakened enough, it often falls due to sudden stresses from wind, snow, rain, falling trees, and the like. Once completely broken off, the short remaining branch stub is gradually overgrown over the years, leaving only a scar on the bark after some time. The thicker the stub the longer it takes. This entire process is referred to as self-pruning or natural stem cleaning. The shedding of dead branches proceeds more rapidly and easily in deciduous trees than in conifers. In case dead branches do not shed completely, the stub of the dead branch remains un-overgrown. The stem then grows around the dead branch, creating a loose or dead knot (Fig. 44-1). The latter knot type negatively affects wood quality, as it can fall out during sawing, impacting the strength and aesthetics of the wood.

In the case of a living branch, the base of the branch grows with the stem during radial growth. As both the branch and the stem grow simultaneously, a fixed connection remains (fig. 44-1). This results in a tight or sound knot (Wang et al., 2024).

Figure 44-1: Growth rings around a living (left) and dead branch (right). Adapted from Heilig (1981).

Once branches are naturally shed or removed through pruning and become overgrown, valuable knot-free wood (knot-free wood zone) starts to be formed. The diameter of the tree at this point is referred to as DOS (Diameter Over Stubs) (Fig. 44-2). It serves as a measure for the diameter of the knotty stem core. Factors influencing the speed of natural stem cleaning include tree species, forest composition, stem density, site and silvicultural treatment. If the goal is to cultivate quality wood, and natural stem cleaning is insufficient to achieve a small DOS, pruning the tree may be considered.

Figure 44-2: Stem section showing the diameter over stubs (DOS, d in figure) and the total stem diameter D. A small DOS and a large knot-free diameter (D-d) are important factors of timber quality.

44.2.2 Branch attachment and wound responses

To determine the correct pruning technique, it is essential to understand the structure of branch attachments, the wound responses of trees, and where compartmentalization occurs at the branch base.

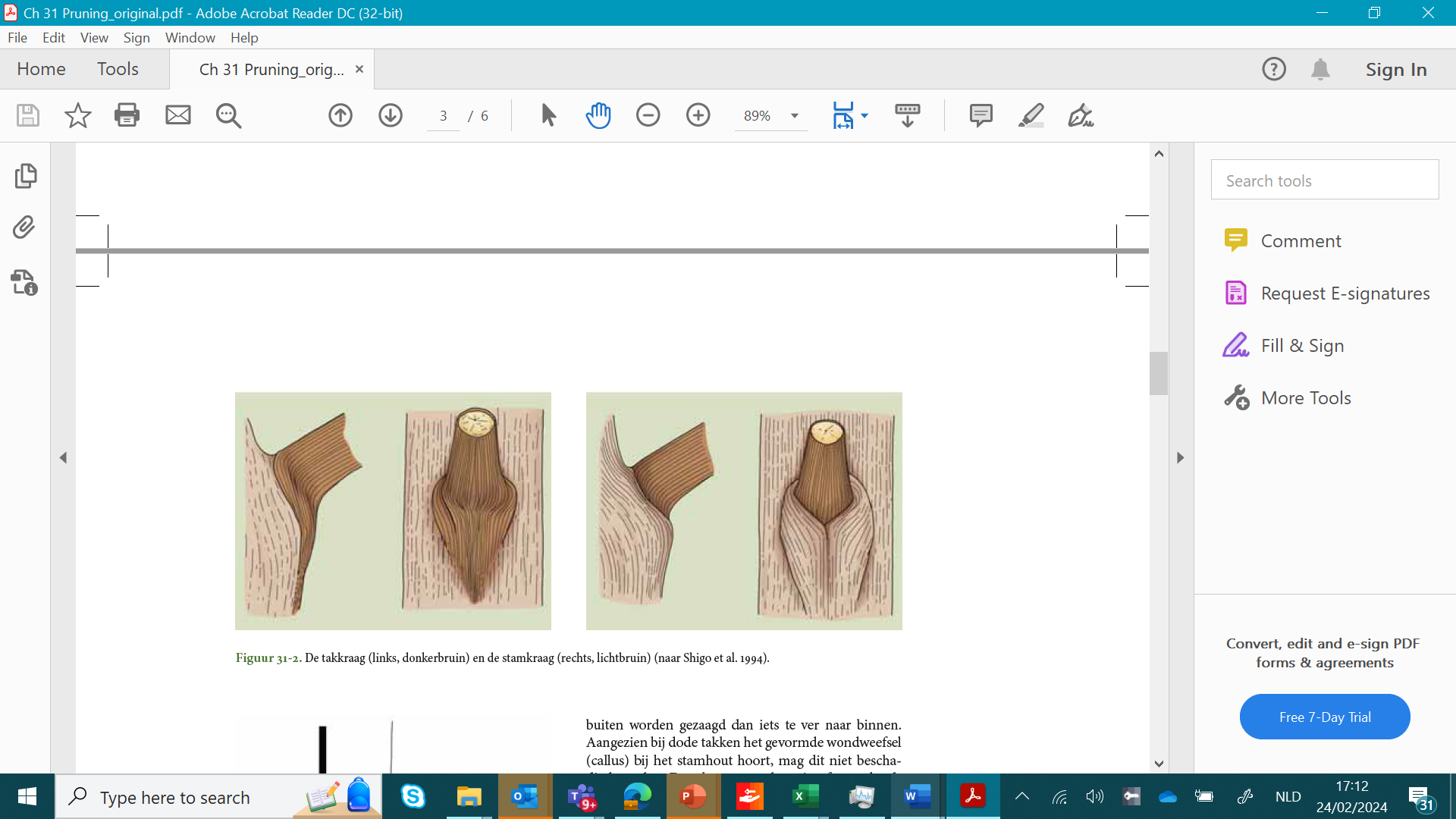

Branch tissue is formed earlier in the growing season than stem tissue. The new branch tissue at the branch base bends steeply downward, meeting underneath the branch (Figure 44-2). The vessels from the branch do not merge with the stem tissue on the sides and above the branch. In this way, the branch tissue encircles the branch base, resulting in a thickened rim around the branch, known as the branch collar. In many tree species, this branch collar is easily recognizable. Later in the growing season, as the xylem in the stem begins to develop, stem tissue grows over the branch collar (Figure 44-3). The stem tissues from this stem collar meet both below and above the branch. Sometimes, the fusion under the branch is not complete, resulting in a depressed area. Thus, a branch is attached to the stem via a series of overlapping branch and stem collars.

Figure 44-3: The branch collar (left, dark brown) and the stem collar (right, light brown) (adapted from Shigo et al., 1994).

When trees are attacked or damaged, for example, through pruning, they respond by forming four compartmentalization zones (Shigo, 1984). At the moment of the attack or damage, the tree forms three reaction zones in the branch base that are close to each other. Reaction zone 1 is formed in the wood vessels, preventing the spread of fungal attacks in the vertical direction. In hardwoods, substances based on phenols are deposited in the vessels, while in softwoods, substances based on terpenes (resins) are deposited. Reaction zone 2 is formed on the annual rings, preventing the penetration of the damage deeper into the wood. Reaction zone 3 is formed on the medullary rays, preventing lateral spread. These compartmentalization zones are immediately formed after the attack or damage, ensuring that only the infected wood can decay. In case of attacks by aggressive fungal species, the branch may form reaction zones at multiple locations before reaching the stem.

The fourth reaction zone is created during the formation of new wood on the outer side of the tree. This zone in the newly formed wood is much stronger than the first three zones, which results from changes in the existing wood. Therefore, it is possible for a tree to be completely rotten inside because the first three zones have failed, while the outer layer of new wood is entirely healthy. The overall compartmentalization strategy is generally quite effective. Only exceptionally does a wood-decaying fungus penetrate the tree from branches that have naturally died.

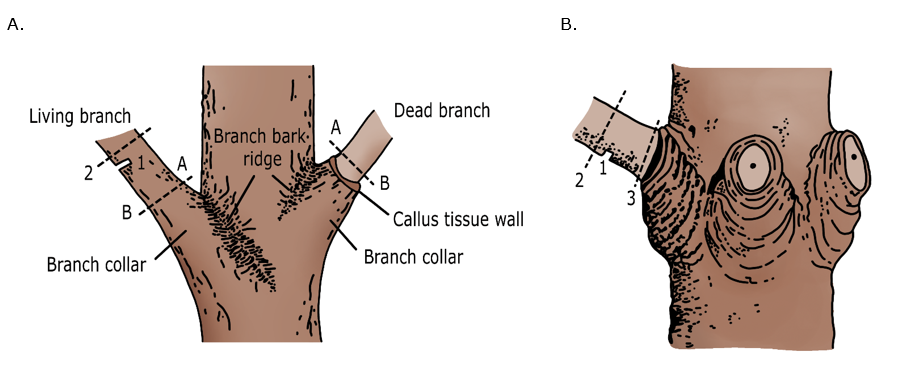

When pruning, consideration must be given to the structure of branch attachments and the compartmentalization of wound tissue. The essence of pruning is to never cut into the stem wood and branch/stem collar because doing so damages the stem and makes it susceptible to attacks. By cutting slightly diagonally from the branch crotch, about perpendicular to the branch bark ridge indicating the transition from stem to branch, the branch attachment and branch collar are not damaged (Figure 44-4). If the branch bark ridge and branch onset are not clearly visible, it is better to cut slightly too far outward than slightly too far inward. Since the formed wound tissue (callus) around dead branches belongs to the stem wood, it must not be damaged. The branch should be cut more or less perpendicular to the length of the branch in the branch crotch (outside the bark ridge) (Figure 44-4). A sloping cut results in poor healing of the branch. Furthermore, it is essential to keep the wound as small as possible by pruning branches when they are still small. Branch scars up to 3 cm in diameter are easily overgrown, although larger scars may be acceptable on trees with fast growth. This reduces the amount of wood the tree needs to compartmentalize, resulting in less assimilate consumption by the tree. Wound healing requires energy and has a measurable impact on growth.

Figure 44-4: The correct pruning method. A. for living and dead branches in broadleaved trees. B. in conifer trees. Heavy living branches are best shortened in two cuts (first the lower short cut 1 and then the upper cut 2) to prevent bark tearing. The branch is then sawn from A to B just outside the branch collar and the callus tissue wall (adapted from Shigo et al., 1994). When pruning with pole saw, cut 1 is not feasible, therefore cut 2 is made directly, but keeping a longer stub.

Formative pruning is pruning in the young stage and early thicket stage, to make early corrections to branching patterns that threaten the stem quality. Formative pruning is aimed at creating a continuous straight stem with minimal taper. Young trees growing in a forest setting generally do not require formative pruning due to mutual competition. However, some tree species or provenances are more susceptible to developing a ‘poor’ stem form with forks or with heavy branches causing strong taper. Usually, there are enough trees to select from during cleaning and thinning operations. In conifers, due to their monopodial growth (see Chapter 4), removal of double tops is only necessary in rare cases. For some broadleaved species, often sympodial species such as oak, formative pruning may be necessary to achieve a single straight stem with minimal taper, especially in case of low stem densities (Kint et al., 2010).

Formative pruning involves the removal of double tops and ‘problem branches,’ such as acute branches and branches with narrow crotch angles. An acute branch is a lateral branch that grows strongly upward, intercepting a lot of light. As a result, it quickly becomes thick, forms a pronounced branch collar, and causes a strong stem taper at the branch attachment point. A narrow crotch occurs with lateral branches that are attached to the stem at a very sharp angle, leading to an incomplete connection between the branch and the stem due to the ingrowth of bark and cambium. Occluded narrow crotch angles create weak connections and can easily tear as the branches continue to grow (Figure 44-5). Narrow angled branches are common, for example, in beech.

Figure 44-5: Narrow crotch angles can lead to occluded bark. Left: a beech stem with a clear occluded bark angle at the top, recognizable by the thickened bark edge (called elephant ear) running from the branch angle along the stem down. Due to narrow crotch angles, the branch cannot grow firmly to the stem. This creates a weak connection that easily tears (right). Photos: Jan den Ouden.

Early intervention is crucial. Since unwanted branching patterns occur in the top of the young tree, formative pruning should target the younger parts of the living crown, effectively from top to bottom. An overview of the most common interventions is given in Figure 44-6. For quality timber production of monopodial broadleaved tree species like common ash and maple, an annual intervention on the not yet lignified shoots (the so-called June pruning) is recommended (Duflot, 1995). Problematic branches do not necessarily need to be completely pruned back to the stem. A significant reduction in the leaf biomass on the branch is sufficient to temper the auxin hormone production (see Chapter 3), resulting in decreased diameter growth, collar formation, and draining of resources.

Figure 44-6: Various examples of formative pruning (red: to be pruned; green: to be retained) (Balleux & Van Lerberghe, 2006).

Stem raising is the pruning in the thicket and pole stage, removing dead or living branches along the stem, increasing the branch free stem section and allowing the production of knot-free timber. In contrast to the formative pruning, this intervention is executed from the bottom of the stem upwards.

The quality and value of timber are strongly influenced by knot density, stem form, and diameter. Knot-free wood is stronger and aesthetically desirable for veneer and furniture production (Bartsch et al., 2020; see also Chapter 2).

Considering growth and vitality of the tree, it is important not to cut too many branches at once. Large saw wounds consume energy, interrupt sap flow over a greater width, and increase the risk of infections. In general, start early in the lifetime of the tree, do not prune too much at once, and come back in time. A rule of thumb is to prune a maximum of 20% of the living branches. Of course, costs play a significant role in determining the pruning regime.

The goal of stem raising is to create the largest possible knot-free zone. Therefore, it is essential to achieve the smallest possible DOS by pruning early and regularly, while from a cost perspective, it is desirable to obtain the desired knot-free stem section with as few pruning operations as possible. A manager must choose between a low DOS in multiple pruning sessions or a larger DOS in one pruning session. Experience shows that, for example, with larch, a DOS of 13 cm is achievable in one pruning session up to 6 m, while for Douglas fir, two or three pruning sessions are needed for this.

The optimal pruned stem height depends on pruning costs and the expected additional economic benefit from knot-free wood. From practice, it appears that a height of about 6 m is optimal. This height can still be reached easily with a pole saw. Above this, stem raising costs increase so much that the additional revenue from the wood often no longer outweighs the costs. During stem raising, living branches can also be pruned; this is then called crown thinning or green thinning. One or even two living branch whorls can be safely removed because these branches contribute only to a limited extent to photosynthesis. Overly aggressive crown elevation leads to a loss of productivity in the tree.

When determining the season for pruning, consideration must be given to the likelihood of infections, insect infestations, water sprout formation, and bleeding (abundant exudation of xylem sap). Pruning of dead branches can take place throughout the year. Living branches in coniferous species are best pruned in winter, as the risk of cambium tearing is minimal. For deciduous trees, pruning is preferably carried out in the months of June, July, and August, when the tree is physiologically active and has active defence against pathogens, faster cicatrization, and lower risk of water sprout formation (Table 44-1). Species from genera Acer, Aesculus, Betula, Carpinus, Carya, Juglans, Laburnum, Ostrya, Populus, Sophora and Salix have intensive spring sap flow, which causes bleeding when wounded before and during leaf onset in spring. Bleeding provokes loss of soluble carbohydrates and bacterial infection. These bacteria can produce toxins that kill cambium and cicatrization tissue. Therefore, these species should be pruned after full leaf development. Pruning poplar from late May to mid-July can reduce the formation of water sprouts.

Table 44-1: Recommended pruning seasons for dead branches and living branches

Especially tree species with poor natural branch shedding and a good market for quality wood are considered for stem raising. Mainly spruce, fir, Douglas fir, larch, Scots pine, and poplar are pruned, but also other deciduous species, such as oak, sweet cherry, black walnut, black locust, and sweet chestnut. To limit costs, only trees with good potential for quality wood should be pruned. In practice, only future trees are pruned. The number of pruned future trees per ha can be calculated starting from the anticipated target diameter at harvest and a D/d ratio (where D is the crown diameter and d is the stem diameter). Conifers have typically a smaller D/d than broadleaved (20 versus 25 on average). For example, in a Douglas fir stand with stem target diameter 60 cm, 62 future trees per ha are selected and pruned (considering a D/d of 20 and a triangular spacing pattern, which has a factor 1.118 less stems/ha than a square pattern). In practice, the selected number of pruned future trees per ha will be maximum 30-60 per ha for deciduous trees and 50-80 per ha for coniferous species. An additional advantage of pruning future trees is that they can be easily recognized without further marking due to the branch-free stem section.

The decision to prune can have consequences for other management measures such as planting, designating future trees, and thinning. Since natural branch shedding plays a lesser role when pruning is performed, especially with hardwood, a smaller number of plants (wider plant spacing) may suffice, reducing some of the stand establishment costs.

Normally, an even-aged stand is kept closed until the turning point (see Chapter 30) to promote natural branch shedding. In stands where pruning is performed, the selection of future trees must precede pruning, leading to an earlier start of thinnings aimed at freeing up the pruned future trees, especially if they face intense competition from neighbours. This is especially important for species that have difficulty enlarging their crown at a later age, such as larch, birch and poplar.

Through early thinning combined with pruning, trees can develop a large, deep crown, concentrating the growth and maximizing the production of valuable, knot-free wood. A disadvantage of early first thinning can be its high cost, in combination with a low harvesting volume of small trees receiving a low wood price. This means that the intervention can be costly, and it remains uncertain whether it will be offset by the improved growth of valuable future crop trees. Due to the long rotation period, costs early in the stand’s development are highly detrimental to the eventual financial outcome. Regular subsequent thinnings will be needed to maintain a large, deep crown of pruned future trees; their crowns must eventually be freed on all sides.

In uneven-aged irregular stands pruning can also be advantageous, where it can compensate for insufficient intraspecific lateral competition. For example, natural seedlings of pedunculate oak under Scots pine generally lack natural stem cleaning, but this can be adjusted by pruning. In this case there is only the pruning cost, no costly precommercial thinning of small dimensions.

Various hand tools have been used for pruning, and attempts have been made to mechanize the process. Currently, hand saws or pruners are used up to 2.5 meters, and pole saws or pruning chisels up to a maximum of 6.5 meters (Fig. 44-7). For higher pruning quality and to avoid the strenuous work with the pole saw, a hand saw with a ladder is also used for high pruning. In plantation forests with wide spacings (e.g. poplar plantations, agroforestry systems with walnut or cherry) mechanical pruners on automotive cherry picker platforms can be applied (Fig 44-7). Electrical pole saws and pole shears have recently been developed. They have certain advantages for pruning thick branches in combination with clearing of undergrowth but they need to be used carefully as the risk of damaging the tree is high.

Fig. 44-7: Common tools used for pruning as a silvicultural intervention (a. pruning saw, b. pruner, c. pole saw, d. pruning chisel, e. pruning ladder, f. cherry picker platform

Pruning is labour-intensive and leads therefore to high expenses in the early stages of stand development, while the pruning bonus, it is the price difference between pruned and unpruned wood, only becomes apparent fifty or more years later at the final harvest. Particularly private forest managers show interest in pruning because they perform the work themselves and may not charge labour costs. However, a cost/benefit analysis using a common interest rate shows that pruning can be profitable. A good premium for quality wood at final harvest will only be obtained if the forest manager can demonstrate to the wood buyer that pruning was performed, what the DOS was at the time of pruning, and to what height the trees were pruned. Good record-keeping is necessary for this because there is a long time between pruning and the sale of pruned wood. To provide more certainty to the wood buyer, the pruning work can be independently certified (Jansen 1999).

Formative pruning is less labour intensive than stem raising. A major benefit is that one can positively influence the number of options and/or future trees by taking away a few problematic branches at the right time. Disadvantage is that one need qualified people to do this job.

References

Balleux P. & Van Lerberghe Ph. 2006. Guide technique pour des travaux forestiers de qualité. Ministère de la Région Wallonne, DGNRE, DNF, Namur, Fiche technique no. 17.

Bartsch, N, Burghard von Lüpke, B. & Röhrig, E. 2020. Waldbau auf ökologischer Grundlage. Ulmer, 8. Auflage. 676 S. DOI: 10.36198/9783838587547.

Duflot, H. 1995. Le frêne en liberté. Institut pour de développement forestier, Paris.

Heilig, P.M. 1981. Houtvademecum. Kluwer, Deventer.

Jansen, P.A.G. 1999. Certificeren van opsnoeien. Stichting Bos en Hout, Wageningen.

Kint, V., Hein, S., Campioli, M., Muys, B., 2010. Modelling self-pruning and branch attributes for young Quercus robur L. and Fagus sylvatica L. trees. Forest Ecology and Management 260: 2023–2034. Doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.008

Shigo A.I. (1984). Compartmentalization – a conceptual framework for understanding how trees grow and defend themselves. Annual Review of Phytopatology 22, 189-214.

Van Alphen B.H.G (1983). Het opsnoeien van bomen. Doctoraalscriptie Vakgroep Bosbouwtechniek. Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen.

Wang, C., Guo, J., Wang, H., Hein, S. & Zeng, J. 2024. Natural Pruning and Branch Growth Dynamics of Young Betula alnoides in Response to Planting Density. Available at

SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4718356 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4718356

Glossary

Self-pruning: The natural process of shedding branches that have been shaded or diseased. This process is more developed among broadleaved trees than conifers. Also called cladoptosis or natural stem cleaning.

Formative pruning: Correction of branching patterns in the sapling stage of a tree aiming at securing the stem quality. Also called training.

Stem raising: Removal of dead or living branches along the stem in the thicket and pole stage of a tree, increasing the branch free stem section and allowing the production of knot-free timber. Also called stem pruning.

Diameter over Stubs (DOS): Stem diameter of the knotty stem core reached once branches are naturally shed or removed through pruning and become overgrown, and when valuable knot-free wood starts to be formed.

Quality timber: Timber meeting high quality standards in terms of dimensions, straightness, absence of knots and other mechanical and esthetical indicators of economic value.

Acknowledgements

This Chapter is published on the EUROSILVICS platform, established as part of the EUROSILVICS Erasmus+ grant agreement No. 2022-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000086765.

This chapter was first written and published as a Dutch chapter in the book Bosecologie en Bosbeheer (Acco, 2010) with authors Patrick Jansen, Robbie Goris and Bart Muys. In 2024 the text was translated to English and fully revised with inputs from Peter Spathelf and the original authors.

Author affiliation:

|

Prof. Spathelf, Peter |

HNE Eberswalde |

|

Jansen, Patrick |

Bosmeester advies |

|

Goris, Robbie |

Goris advies |

|

Prof. Muys, Bart |

KU Leuven |

Illustrations: Sylvia Grommen