Chapter 67: Mountain Forests – Download PDF

Authors: Hubert Hasenauer, Timm Horna

Author affiliations are given at the end of the chapter

Intended learning level: Basic

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

| Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

| This chapter explains the management of alpine forests to sustain protection, water regulation and economic use. It describes management practices and potential problems for forest managers. |

NOTE: this part is a full draft, which in due time will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

67.2 Background – The many roles of forests in Austria 2

67.3 Historical importance of mountain forests 4

67.4 The role of protective forests 5

67.5 Management for rockfall protection 7

Concluding remarks on rockfall protection 9

67.6 Management for avalanche protection 9

Concluding remarks on avalanche protection 10

67.7 Management for landslides and debris flow 10

67.8 Current forest management 11

67.9 Fate of protective forests in Austria 12

Austria is one of Europe’s most forested countries, and its forests deliver a wide range of public services, from clean water, climate regulation, biodiversity and habitat provision to timber, recreation and cultural values, for both people and nature.

Mountain forests form a protective belt in a country where the Alps dominate large amounts of the surface area. These forests cover the Alps and their foothills, where steep terrain and complex geological situations are confronted with dense human settlements. Around 65% of the national territory of Austria is classified as being part of the Alps (Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Regionen und Wasserwirtschaft, 2019).

By law, Austrian forests are managed for multiple functions (Production, protection, „welfare“ and recreation), with protection against natural hazards being the dominant function and taking precedence in most high relief landscapes. In these regions, the forest can be classified as “living infrastructure”, as it prevents or at least buffers rockfall, avalanches, landslides and debris flow. Thus, forest management has to be tailored towards stability and general risk reduction, while in many steep areas, good soil and climate also allow for good yields.

This chapter will focus on the management of the Austrian mountain forests, with an emphasis on natural regeneration strategies and the handling of key threats.

67.2 Background – The many roles of forests in Austria

As mentioned before, forests in Austria fulfil multiple roles by law:

- Production

- Protection

- Welfare (includes clean air and water)

- Recreation

The production function indicates the economic use of the forest and is assumed as the principal function of each forest unless stated otherwise under the forest development plan for Austria (Grieshofer and Wiesinger, 2021). The welfare function covers the forest’s environmental benefits, especially climate regulation, water balance regulation, and the cleaning and renewal of air and water. The recreation function denotes the forest’s effect as a space for recreation and recovery for visitors and is often found around large cities, for example around Innsbruck in Tyrol.

For the protective functions Austrian mountain forests provide, they operate under tight constraints that shape how they are managed and financed. Margins are often low because the terrain makes timber extraction costly, and management faces multiple limitations: legal requirements, economic viability and ecological realities of the site.

Economically, protective forests can be characterised in the following two ways:

Protection forest with yield

This is protection forest whose primary function remains protection, but which is managed under specific conditions. Planned harvesting is permitted, as long as the protective effect is not diminished. Typical features include small-scale interventions, longer cutting intervals, higher residual stand densities, and strict skid-trail layout.

Protection forest out of production

Here, planned timber harvesting is discontinued. The reasons are usually high hazard levels, lack of access infrastructure, or the impracticability of interventions, for example in very steep or difficult terrain. Measures are limited to conservation, tending, and risk mitigation to secure the protective function.

Protective forests may also be split up into two different categories according to their function: Site-protection forests are stands whose primary function is to stabilize the ground they occupy, protecting soils and slopes from erosion and shallow mass movements caused by rainfall, runoff, frost, wind, and gravity. In site-protection forests, revenues from regular forestry are expected to cover silvicultural costs.

By contrast, object-protection forests shield specific people or infrastructure; there, other beneficiaries can be asked to co-finance necessary measures. Where defined natural hazards are present and the public interest in protection clearly prevails, authorities can declare forests as “Bannwald,” enforcing stricter rules for use and harvesting. Such designations can impose financial disadvantages. In these cases, owners are entitled to compensation. Together, these mechanisms balance public safety with private ownership in challenging alpine conditions.

Ecologically, mountain forests may span montane to subalpine elevations, from 600 to more than 1900m above sea level. Simultaneously, the underlying soils and bedrock impact the forest type above: On carbonates and mixed substrates, mixed stands of Norway spruce (Picea abies), silver fir (Abies alba) and European beech (Fagus sylvatica) dominate. Higher up, larch (Larix decidua) and Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra) take over and form stands.

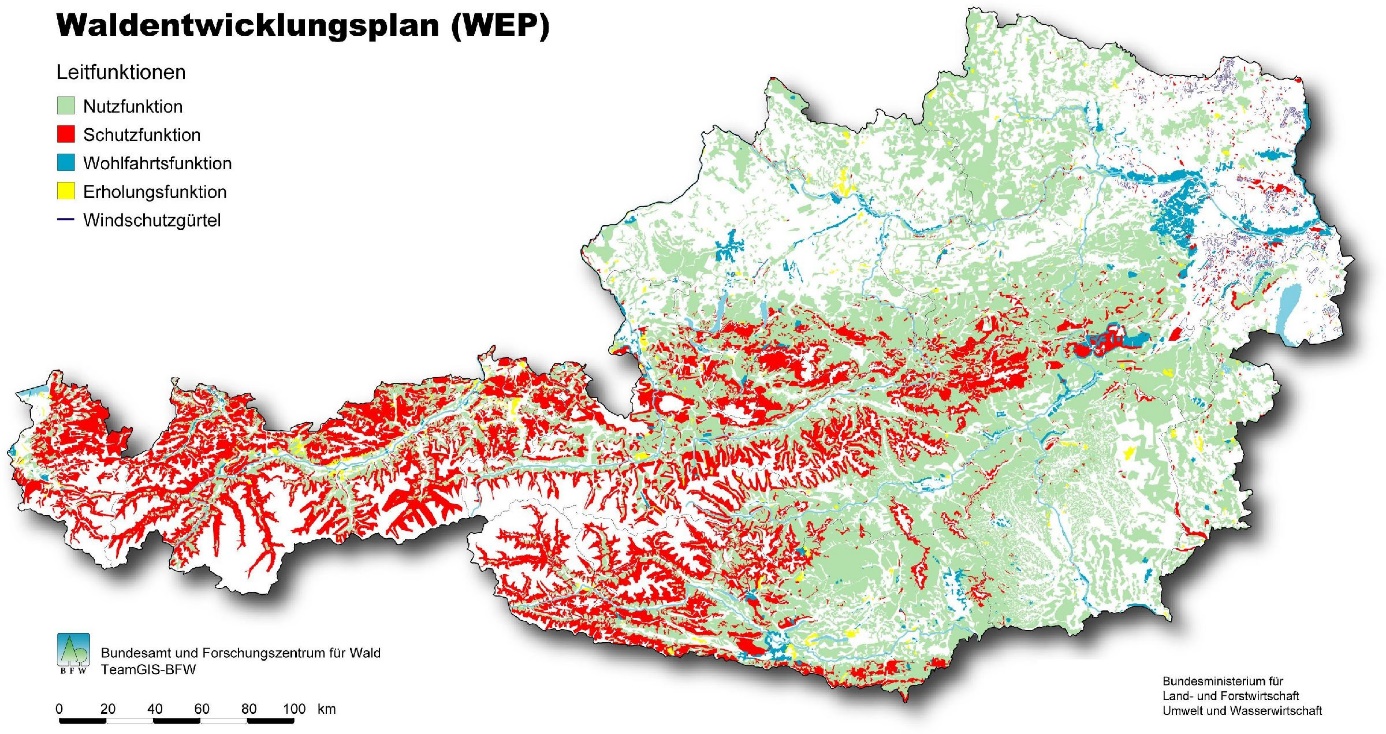

Figure 67-1 Dominating forest functions in Austria. Red colour indicates that the protective function of the forest is deemed the most important. The distribution of the protective forests large coincides with the alpine range in Austria (Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Regionen und Wasserwirtschaft, 2025).

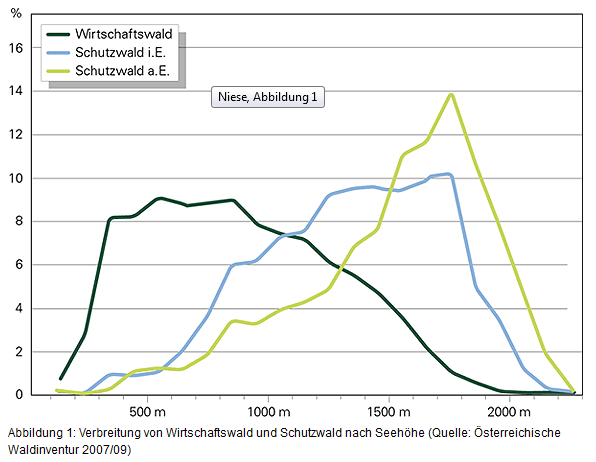

Figure 67-2: Distribution of forest types (commercial forest, protective forests with yield, protective forest without yield) in Austria across an altitude gradient. The share of commercial forest decreases with increasing altitude. Above 1800m, protective forests without yield dominates .

67.3 Historical importance of mountain forests

Historically, Austria’s mountain forests have evolved from being purely economically exploited to important landscape features as “multi-use forestry”. Early mountain forestry featured large clearcuts to supply the mines and saltworks. Overuse led to increased erosion, which was intensified by the creation of alpine meadows. As a result of this, the treeline today is often hundreds of meters lower than it would naturally be, and only due to recent climate change has the treeline started to shift upwards again.

During the age of industrialization, mountain forests were frequently exploited through the use of large-scale clearcuts. Managing regeneration was initially not a priority, and these openings were left to natural succession. However, professional production of forest planting stock became established, which enabled the artificial regeneration of stands through planting which shortened rotations and allowed for even afforestation without gaps.

In today’s mountain forests, clear cuts remain common because they allow for high productivity during harvests and help offset the considerable extraction costs in steep terrain, which is often only possible using cable yarding. Clearcuts also mirror the natural disturbances encountered in mountain forests: windthrow and avalanches, as well as snow break often lead to large-scale openings in the forest canopy. This aligns with the regenerative dynamics of some typical montane species such as Norway spruce (Picea abies) and European larch (Larix decidua), which are light-demanding in their youth. Following a clear cut, they experience full light conditions which promotes their establishment and early growth.

67.4 The role of protective forests

Forests function as living infrastructure. Through canopy interception, rainfall peaks are attenuated and immediate surface runoff is reduced while infiltration is promoted. At the same time, root systems stabilize the topsoil, which lowers the risk of erosion and landslides. In combination, these processes reduce the probability of debris flows.

This is particularly relevant not only for Austria but the Alps in general. Steep, short catchments rapidly concentrate rainfall and mobilize material. The mixture of water and sediment is funnelled downhill through steep ravines and deposited further down. These deposition zones are often located in permanently settled areas, which puts buildings, roads, and other infrastructure at direct risk. Therefore, maintaining healthy protection forests is of high importance for public safety.

The objective of mountain forest management is to maintain a permanently stocked, closed canopy that is ideally also economically viable and operates profitably. Stability is the central focus. Interventions are conducted bottom-up (“working uphill”) and against the prevailing wind direction, which in Austria and much of Central Europe is predominantly westerly. Natural stand dynamics are taken into account. Group-wise (“Rotte”, German for “gang”) structures are retained to buffer the impacts of snow and wind across multiple individuals, which often originate from vegetative reproduction. Windthrow and winters with heavy snow are among the most important abiotic factors in protection forests because they can damage stands and open large gaps. Such openings increase the risk of biotic damage.

Bark beetle populations often benefit from prior disturbances such as storms and can build to mass outbreaks. The Kaprun Valley offers a clear example. After a foehn storm in 2002 caused extensive windthrow, large areas were subsequently deforested by bark beetles. Measurements recorded increased runoff in the catchment. As a result, the forest’s protective function was markedly reduced (Zandl and Czadul, 2024).

Figure 67-3: The Alps dominate large parts of Austria. Forest management must be adapted to mountainous conditions to ensure that all forest functions are fulfilled.

Figure 67-4: Left: Artificial avalanche protection measures on the mountain slopes above a protective forest. Right: Avalanche path in an Austrian mountain forest.

67.5 Management for rockfall protection

Goals:

- Prevention of rockfall caused by forest

- Deceleration of falling rocks in the forest by reducing kinetic energy

- different tree species have different abilities of slowing down trees.

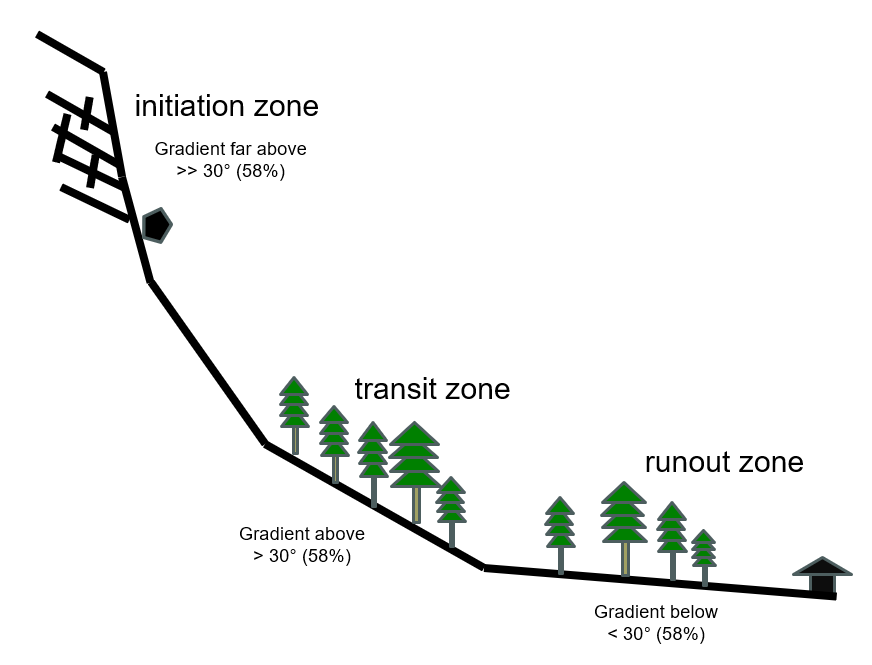

Rockfall refers to the descent of individual rock blocks typically below 5 m³ in volume (Wehrli et al., 2007), driven mainly by natural weathering but sometimes triggered by trees, for example, when windthrow and uprooting loosen embedded blocks. In mountains, rockfall is a natural process, evident from talus/scree deposits and block fields. Events often occur spontaneously and are especially common in spring during snowmelt, when previously detached blocks that had been temporarily “braced” by snow are released and continue downslope by rolling or bouncing. These rocks can reach very high speeds and thus pose a significant hazard to people and to infrastructure such as roads, buildings, and utilities.

The mechanical energy a rock carries as it moves downslope is the sum of its potential and kinetic energy, governed largely by its size, the fall path, and its bounce height. This energy can be absorbed or reduced by technical measures such as rockfall nets. Protective forest within the rockfall path can also dissipate energy: trunks, crowns, and deadwood slow rolling and bouncing blocks, deflect their trajectories, and thereby lower impact energies (Perret et al., 2006).

The energy transmitted to a tree in the path of a moving or falling rock can cause stem breakage, bark and wood injuries, or even overturning of the tree. The goal is therefore to reduce the speed of the blocks in order to lower the impact energy; even protective forests remain only partly effective against very large blocks. As stem diameter increases, braking effectiveness rises, and high stem densities should be sought because this spreads the braking over many contacts and deflects trajectories more often. In practice, however, the maximum achievable stem density is limited by tree species composition, age structure, and site conditions.

Forests prevent, slow, and can even stop falling or rolling rocks. Once a rock is in motion, trees act as braking elements. The braking effect and energy absorption depend largely on the bending moment that the stem and root plate can take up. This bending moment can be described by tree characteristics such as stem diameter, wood strength, height, and root anchorage, and it is species specific. As a result, the composition and structure of a stand determine how effectively a protective forest decelerates and stops rolling or bouncing rocks.

Gsteiger (1993) came up with the concept of the average tree-free distance a block travels downslope between two effective tree impacts (Gsteiger, 1993). This characterizes the potential of a forest stand to slow down or stop blocks. Rockfall energy scales with distance and speed. Keeping the average tree-free distance short limits the rock’s kinetic energy and increases the likelihood that a rock is stopped higher up on the slope.

A practical constraint is the inverse relationship between stem number and average diameter. As trees grow larger, their numbers per hectare decline to stay within the site’s carrying capacity. Management therefore balances sufficient stem diameter for strong braking with enough stems to keep average tree-free distances short, within the limits set by species mix, age distribution, and local site conditions.

Box 1: Stages of rockfall (based on Frehner et al., 2005)

Box 2: Silvicultural recommendations for rockfall protection for each zone

Initiation zone:

- Prioritize rooting and slope stability. Aim for trees that are anchored well in the soil to avoid forest-triggered release of rocks

- Remove or avoid maintaining unstable, top-heavy trees that could fail and loosen embedded rocks

- Select species and structures that build strong, deep root systems. The goal here is prevention rather than braking

Transit zone:

- Following Gsteiger’s concept, keep the average tree-free distance short along expected fall lines

- Short tree-free paths limit speed and thus, kinetic energy. 20m is ideal, avoid values above 40m.

- Where possible, favour larger diameters. Aim for at least 400 stems/ha, with spacing between the trees under 20m in the fall direction

- Broadleaves are preferable as they are less prone to breaking.

- Use silvicultural methods that preserve braking elements when harvesting. Leave high (~1.5m) stumps and fell trees diagonally across the slope to increase contact and shorten effectively tree-free paths.

Runout zone:

- Keep tree-free paths short to create frequent contacts.

- Still aim for 400 trees/ha and stem-spacing of below 20m.

- Diameter is still helpful but less critical here due to lower slope.

Concluding remarks on rockfall protection

Well-managed forests are a cost-effective first line of defence against rockfall. By maintaining stable source areas, keeping average tree-free distances short in transit and runout zones, and favouring structures and species that absorb impact energy, we can significantly reduce rock speeds and risks. Where forests are absent or fail to meet the protective function, protection relies on expensive engineering measures such as rockfall nets. It is therefore in our clear interest to manage protective forests actively, so they deliver reliable, affordable risk reduction over the long term.

67.6 Management for avalanche protection

Avalanche are among the most consequential natural hazards in mountain regions. They occur when shear stresses within the snowpack exceed its internal strength. Slopes between approximately 30 and 45 degrees are most susceptible. Release can occur spontaneously during snowfall and wind, during periods of warming or rain on snow, or as a result of additional loading such as skiers. A primary distinction is between loose-snow avalanches and slab avalanches, with the latter posing the greatest danger because a cohesive slab fails on a weak layer and accelerates rapidly.

Every avalanche traverses three characteristic zones, similar to the rockfall stages previously discussed. In the release or starting zone, snow accumulates and consolidates until failure occurs. In the avalanche track, the moving mass descends and gains kinetic energy. In the runout zone, the flow decelerates and deposits. Hazard levels depend on slope angle, aspect, terrain morphology, surface roughness and the prevailing snow climate.

Forest influences several of these determinants simultaneously. In closed, well-structured stands, tree crowns intercept and redistribute snowfall, which reduces ground-level accumulation and dampens wind transport that would otherwise produce drifted snow and wind slabs. Trunks, roots, and understory vegetation anchor the snow cover and increase surface roughness, thereby lowering the likelihood of extensive fracture propagation and diminishing basal sliding.

Forest also modifies the snowpack microclimate. Shading attenuates diurnal temperature fluctuations and can limit the formation of weak layers driven by strong temperature gradients (Höller, 2001). Canopy drip and the heterogeneous distribution of snow produce a more spatially variable, and often more stable, snowpack than on open terrain. Effective protection requires stands that are closed, multilayered, and spatially clumped. Large openings accelerate wind and promote drift formation. At stand edges, leeward accumulations can build potential release zones.

Within the avalanche track, forest reduces momentum through roughness and obstacles. Trees, stumps, coarse woody debris, and dense regeneration absorb energy and can deflect or fragment the flow. This braking effect is finite; very large or wet avalanches may overrun forested areas. Nevertheless, structurally rich stands commonly reduce velocity and shorten runout distance. Research has shown that stand density has a strong effect on reducing the energy of avalanches, where doubling the number of trees increases the amount of avalanche mass retained eightfold (Védrine et al., 2022).

In the runout zone, forest facilitates earlier deposition. Shrubby layers and dense young growth enhance friction and help retain deposits, which in turn diminishes erosive impacts. Without such roughness elements, avalanches can penetrate farther into valley floors and increase damage to infrastructure, settlements, and transport corridors (Feistl et al., 2014).

Box 3: Silvicultural recommendations for avalanche protection (Frehner et al., 2005)

Starting zone:

- The canopy should be kept closed. Gaps should be kept small and regeneration should be achieved gap by gap.

- Target high canopy cover and stem density, and avoid creating wide corridors. Single-tree selection systems should be preferred over large cuts

Avalanche path:

- Increase surface roughness by maintaining high stem numbers, especially in younger forest development phases

- The understorey and shrubs also help to slow avalanches.

- Thinning should not create corridors. The “Rotte” forest structure should be maintained

Runout zone:

- Braking works best in dense, multi-layer stands with high stem numbers

Concluding remarks on avalanche protection

Forest acts preventively in the release zone, braking within the track, and stabilizing in the runout zone. It cannot replace engineering measures in all settings, but across much of the alpine landscape it represents the most important and sustainable protective element. To maintain this function, stands should be managed for stability and structural diversity, with small intervention areas, long crowns, and a closed stand margin. Where forests are sparse, overmature, or degraded, avalanche hazard and potential impacts increase.

67.7 Management for landslides and debris flow

Forests lower the likelihood of landslides and debris-flow initiation by using and buffering water on site. In protective mountain forests, management should aim to keep water within the canopy–soil system so it never concentrates into fast surface runoff on steep slopes. The guiding principle is: „Water should be retained and used on the site“ via interception, transpiration, and infiltration.

First, canopy interception: foliage and branches catch a large fraction of rainfall and snow, which can then evaporate before reaching the ground. Generally, conifers show higher interception compared to broadleaf trees (Herbst et al., 2008). Thus, in mountain forests, interception can reach up to ~50% of gross precipitation (Raleigh et al., 2022), and the strength of this effect scales with leaf area index (LAI), as a high LAI is directly tied to hydrologic buffering.

Transpiration returns soil water to the atmosphere, reducing pore water pressures that would otherwise weaken shallow soil layers on steep slopes. Stand development and density influence water-use efficiency and total evapotranspiration, linking silviculture to catchment water yield over seasons.

Infiltration and storage: intact forest floors, litter, and undisturbed soils increase infiltration. As a rule, surface runoff is generally absent within forest stands, so rainfall enters and is stored in the profile instead of flowing downslope. Where canopies are removed (through clearcuts or windthrow) or soils are compacted, this buffer collapses and runoff and peak flows rise. These conditions can cause landslides and debris flows.

Beyond impacting hydrology, forests provide mechanical reinforcement through their roots. Deep, well-distributed roots bind soil together and add cohesion along shallow slopes. It is essential that forest cover remains on these slopes, as removing the stands may lead to increased erosion which may remove all soil.

Box 4: Recommendations for landslide and debris flow protection

- Maintain high canopy cover to maximize interception and transpiration and avoid large openings on steep slopes.

- Select tree species with strong rooting adapted to the local geology.

- Use small-scale regeneration methods to preserve canopy function and maintain the “Rotte” structure, as stability is the most important goal for all phases of growth

- Thinning should be done early to allow trees to grow with long crowns and low H/D ratios.

- Carefully plan forest access, as high road density leads to more compaction and thus lower infiltration

67.8 Current forest management

Mountain forests can be highly productive, which is amplified through global warming, as it has increased the length of the vegetation period (Wieser et al., 2019). At the same time,

Even today, clear cuts are the dominant method of forest regeneration where the protective function is secondary to economic goals of forest management. Where the protective function of forests must be guaranteed, different methods of regeneration are used, with narrow strip fellings (“Schlitzhiebe”) being common in the mountainous regions of Austria.

This regeneration method is aligned with the preferred extraction technique on steep terrain, cable yarding. A Swiss forestry officer observed that spruce regenerates well in narrow cable corridors (Hirsiger et al., 2013). In practice, strips are cut across the fall line; their width upslope and downslope must not exceed one tree length (Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung, 2019). Horizontally, the length of the strip is not prescribed, but is effectively limited by the length of the cable used for lateral inhaul, since productivity declines as strip length increases.

By adjusting strip width, analogous to group selection, the species mix can be controlled: narrower strips favour shade-tolerant species, whereas wider strips benefit light-demanding species such as larch. The size and shape of the strips should be adapted to aspect and slope inclination, with solar radiation also taken into account (ARGE Alp, 2014). In addition, strips should alternate and not directly touch one another, in order to avoid creating large open areas. The areas immediately upslope and downslope of a given strip can be used in the next or subsequent entry, so that an age-diverse mosaic of forest and regeneration patches develops across the slope in protection forest. In this way, the protective function can be maintained over the long term while securing regeneration.

Figure 67-5: There is no regeneration outside the fenced area, indicating strong browsing pressure caused by abundant wildlife.

67.9 Fate of protective forests in Austria

Austria’s protection forests are widely affected by overaging and weak stand structure. In many spruce-dominated stands that were established as even-aged forests, the absence of timely thinning has produced overly dense, homogeneous canopies with little vertical or horizontal differentiation. Such stands are vulnerable to disturbance and provide a fragile basis for long-term protective functions (Niese, 2011). Biotic disturbances, particularly bark beetle outbreaks, are considered the most significant threat to spruce-based protection forests in the Austrian Alps. High ungulate densities compound the problem by suppressing the regeneration of much-needed admixture species, which in turn prevents the transition toward more resilient, mixed stands (Irauschek et al., 2016).

Silvicultural responses should aim to shorten the regeneration phase while preserving protection. Underplanting beneath a partial overstory can accelerate the establishment of the next cohort and help maintain continuous protective effect. Where seed trees are lacking, direct seeding is a viable option, provided that protective microsites and suitable substrates are present (Kutscher et al., 2011). Site-specific conditions and human influences matter: in areas with heavy tourism pressure, for example in parts of Tyrol, reduced browsing can favour the regeneration of silver fir (ARGE Alp, 2014).

Deficits are particularly pronounced at higher elevations. Between 1,600 and 1,800 meters, about 35 percent of protection forest lacks adequate regeneration. Steep slopes, insufficient light, and competing ground vegetation are common causes of failure (Schüler et al., 2023). Addressing these constraints requires careful design of canopy openings, protection of regeneration from browsing, and active management of competing vegetation, all tailored to the microclimatic realities of high-mountain sites.

Finally, scale matters for implementation. Schüler et al. (2023) estimate that the number of seedlings required for large-scale reforestation of protection forests would be roughly ten times Austria’s current annual nursery production. A pragmatic strategy therefore combines targeted planting where artificial regeneration is indispensable with the widest possible use of natural regeneration wherever seed sources are present. This mixed approach aligns production capacity with ecological opportunity and increases the likelihood of rebuilding diverse, structurally stable protection forests over time.

Austria’s mountain forests perform a range of functions outlined in this chapter. Proper management is of the utmost importance to ensure these functions can be maintained over the long term. With climate change and rising disturbance risks (wind, bark beetle, drought) we need diverse, structurally rich forests: small-scale regeneration under cover, mixtures matched to site, careful soil and water protection, and access planning that disperses rather than concentrates flow. Where forests cannot provide sufficient protection, engineering measures are necessary; yet in many places, a well-managed protection forest remains the most economical and ecological solution. The goal is continuous care that increases resilience over decades.

Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung, 2019. Waldtypisierung Tirol: Begriffe & Definition.

ARGE Alp, 2014. Ökonomie und Ökologie im Schutzwald.

Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Regionen und Wasserwirtschaft, 2025. WEP AUSTRIA – DIGITAL [WWW Document]. Waldentwicklungsplan Österr. URL https://www.waldentwicklungsplan.at/map/?b=09X9&layer=ERIWGg&x=1697437&y=6072310&zoom=10 (accessed 10.22.25).

Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Regionen und Wasserwirtschaft, 2019. Alpenkonvention in Österreich [WWW Document]. Alpenkonvention Österr. URL https://www.bmluk.gv.at/themen/klima-und-umwelt/eu_international/alpenkonvention0/oesterreich.html (accessed 10.21.25).

Feistl, T., Bebi, P., Teich, M., Bühler, Y., Christen, M., Thuro, K., Bartelt, P., 2014. Observations and modelling of the braking effect of forests on small and medium avalanches. J. Glaciol. 60, 124–138. https://doi.org/10.3189/2014JoG13J055

Grieshofer, A., Wiesinger, C., 2021. Waldentwicklungsplan – Richtlinie über die bundesweit einheitliche Erstellung, Ausgestaltung und Darstellung des Waldentwicklungsplans.

Gsteiger, P., 1993. Steinschlagschutzwald: Ein Beitrag zur Abgrenzung, Beurteilung und Bewirtschaftung. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 144, 115–132.

Herbst, M., Rosier, P.T.W., McNeil, D.D., Harding, R.J., Gowing, D.J., 2008. Seasonal variability of interception evaporation from the canopy of a mixed deciduous forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 148, 1655–1667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2008.05.011

Hirsiger, E., Gmür, P., Wasem, U., Wunder, J., Brang, P., 2013. Verjüngung von Gebirgs-Fichtenwäldern. WALD HOLZ 13.

Höller, P., 2001. The influence of the forest on night-time snow surface temperature. Ann. Glaciol. 32, 217–222. https://doi.org/10.3189/172756401781819256

Irauschek, F., Rammer, W., Langner, A., Lexer, M., 2016. Sicherung der Schutzfunktionalität österreichischer Wälder im Klimawandel. Endbericht von StartClim2015 (No. D), StartClim2015: Weitere Beiträge zur Umsetzung der österreichischen Anpassungsstrategie. BMLFUW, BMWF, ÖBF, Land Oberösterreich.

Kutscher, M., Bayer, E.-M., Göttlein, A., 2011. Chance oder Risiko? Saat im Schutzwald. Waldforschung Aktuell 43.

Niese, G., 2011. Österreichs Schutzwälder sind total überaltert. BFW Praxisinformation 24, 29–31.

Perret, S., Baumgartner, M., Kienholz, H., 2006. Inventory and analysis of tree injuries in a rockfall-damaged forest stand. Eur. J. For. Res. 125, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-005-0082-6

Raleigh, M.S., Gutmann, E.D., Van Stan II, J.T., Burns, S.P., Blanken, P.D., Small, E.E., 2022. Challenges and Capabilities in Estimating Snow Mass Intercepted in Conifer Canopies With Tree Sway Monitoring. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR030972. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030972

Schüler, S., Ijjas, F., Freudenschuss, A., Gschwantner, T., Konrad, H., 2023. Evaluierung des Bedarfs und möglichen Angebots an Saat- und Pflanzgut für den Schutzwald.

Védrine, L., Li, X., Gaume, J., 2022. Detrainment and braking of snow avalanches interacting with forests. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 1015–1028. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-1015-2022

Wehrli, A., Brang, P., Maier, B., Duc, P., Binder, F., Lingua, E., Ziegner, K., Kleemayr, K., Dorren, L., 2007. Schutzwaldmanagement in den Alpen – eine Übersicht | Management of protection forests in the Alps – an overview. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 158, 142–156. https://doi.org/10.3188/szf.2007.0142

Wieser, G., Oberhuber, W., Gruber, A., 2019. Effects of Climate Change at Treeline: Lessons from Space-for-Time Studies, Manipulative Experiments, and Long-Term Observational Records in the Central Austrian Alps. Forests 10, 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10060508

Zandl, J., Czadul, S., 2024. Wir sind davon ausgegangen, dass sich die Wildtiere stark vermehren werden, wenn man nichts dagegen tut. Falter 47, 52–53.

This Chapter is published on the EUROSILVICS platform, established as part of the EUROSILVICS Erasmus+ grant agreement No. 2022-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000086765.

This chapter is based on the teaching materials of Hubert Hasenauer for his course “mountain forestry” held at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, Austria.

Author affiliation:

| Hubert Hasenauer | Institute of Silviculture, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Austria |

| Timm Horna | Institute of Silviculture, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Austria |