Chapter 48: Nutrient management – Download PDF

Authors: Van Der Bauwhede Robrecht, De Schrijver An, Wuyts Karen, Hartmann Peter, Muys Bart, Mohren Frits

Author affiliations are given at the end of the chapter

Intended learning level: Advanced / Applied (Professional)

This material is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

|

Purpose of the chapter: |

|---|

|

This chapter highlights the historical and ongoing challenges related to nutrient availability in European forests. It outlines how human activities; such as historical land use, industrial emissions, and forest exploitation; have led to accelerated soil acidification and nutrient imbalances, which negatively impact tree health and growth. The chapter also reviews past and current forest nutrient management practices, including fertilisation, liming agents, tree species choice, and exploitation methods. Ultimately, it aims to explore management strategies that can enhance forest resilience and vitality by mitigating the effects of nutrient deficiencies, acidification, and eutrophication. |

NOTE: this text is a complete draft, which will be further revised

and edited following review by the EUROSILVICS Project Board

48.1.1 Problem statement and concepts of forest soil fertility 3

48.1.2 Brief history of forest nutrient management in Europe 7

48.2. Nutrient management through nutrient applications 8

48.2.1 Concepts of forest nutrition 8

48.2.2 Fertilisation and liming 11

48.3. Nutrient management through adapted forest management 16

48.3.2 Forest edge management 19

48.3.3 Method of exploitation and forest nutrient balances 20

48.3.4 Ploughing and litter raking 24

Liming a forest stand anno 2025 in the Netherlands © Chris Schotanus

48: Nutrient management

48.1.1 Problem statement and concepts of forest soil fertility

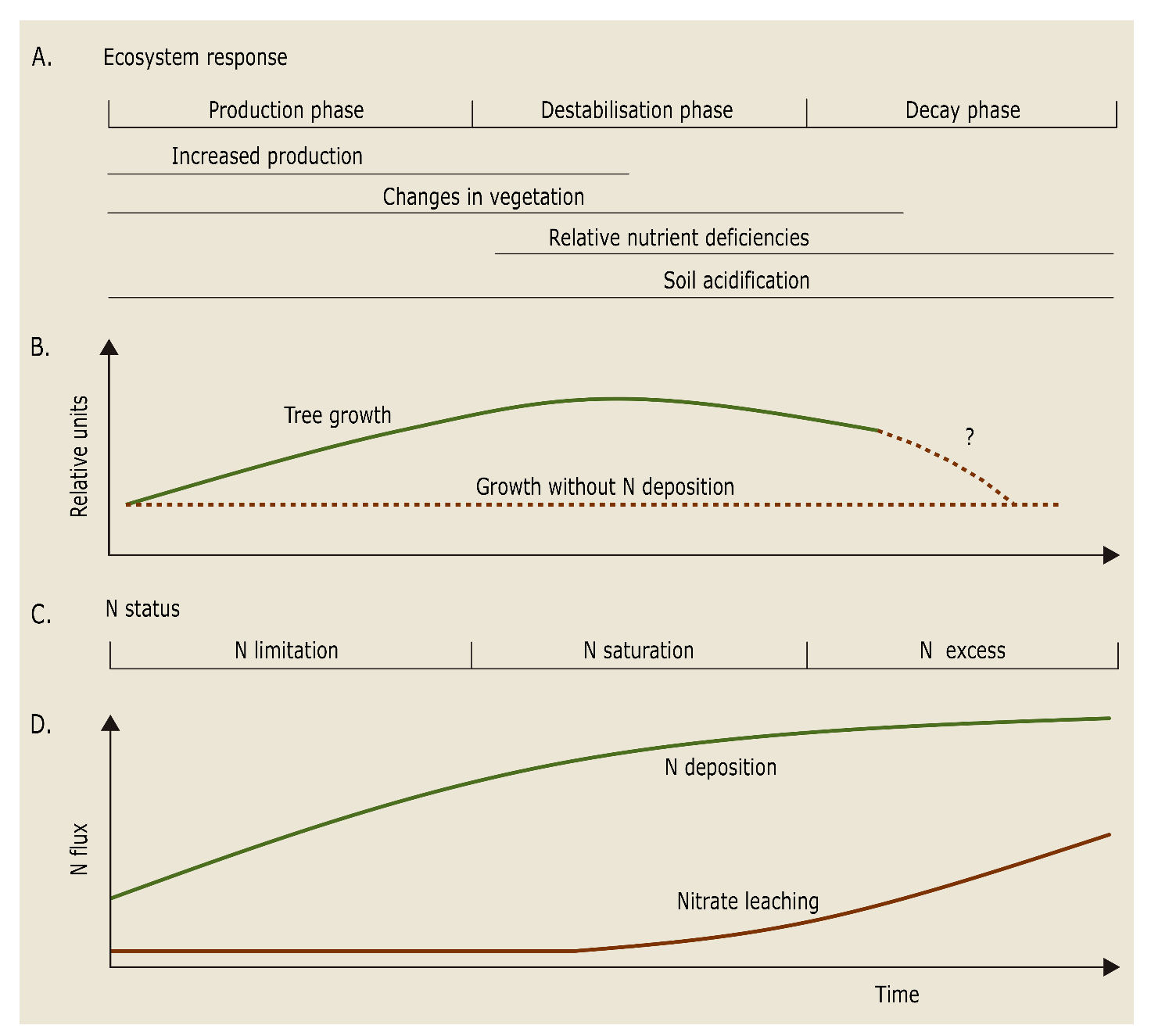

To facilitate optimal tree growth, both macro- and micronutrients must be available in sufficient quantities for tree uptake. However, European forests are often found on less fertile soils, as the more nutrient-rich soils were historically converted to agricultural land. Therefore, macronutrients such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), sulphur (S), and cations like potassium (K+), calcium (Ca2+), and magnesium (Mg2+), as well as micronutrients like iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), boron (B), and nickel (Ni) may become deficient (see also Chapter 14). These nutrients are essential for the synthesis and functioning of amino acids and nucleic acids (N, P, S, Zn, Fe, Mn, Cu), chlorophyl and photosynthesis photosystems (N, Mg, Fe, Mn, Cu), energy production and transfer via ATP (P, Mg, Mn, Fe), cell wall structure and stomatal functioning (Ca, Mg, K, B, Cu) (Marschner, 2012). For centuries, human activities such as wood harvesting and litter raking have further removed essential nutrients from often naturally nutrient-poor forest soils. The resulting nutrient limitations lead to tree growth limitations, i.e., a lowered site index, while micronutrient deficiencies can also lead to growth disturbances, e.g., pendulum growth of the top shoot of Douglas fir when Cu is deficient (Baule and Fricker, 1967). Additionally, mainly since the second half of the 20th century, the incineration of fossil fuels in industry, traffic and households, as well as industrial livestock production led to disruptive anthropogenic emissions of sulphur and nitrogen oxides (SOx and NOx) and ammonia (NH3). Their deposition has accelerated soil acidification leading to a decreased soil pH, changes in the understory vegetation, and critical deficiencies of Ca, Mg or K in the foliage of trees (Figure 48-1).

Figure 48-1: Assumed response of managed forest ecosystems in temperate regions to increased atmospheric N deposition: A: ecosystem response (relative deficits indicate water and nutrients other than N); B: relative changes in growth; C: N status; D: relationship between input and output of N. The time scale (X-axis) for the response depends on ecosystem type and region and, of course, shows high variability. Source: Gundersen et al. (2006).

The pH of a soil forms one of the most critical constraints on its chemical characteristics, plant nutrient availability, toxic ion concentration, soil charge and structure (Ulrich & Sumner, 2012). To determine the soil pH, multiple operationally defined methods exist, i.e., the pH in a 1M KCl or 1 M NaCl suspension of a soil sample. Increasing ionic strength in the extract increases the formation of variable charge and, in forest soils that have variable negative charge, it thus leads to lowered pH values. The ICP-Forests monitoring strategy reports soil pH measured in a 0.01M CaCl2 extract at a solid:liquid ratio of 5 g soil: 25 mL solution (Cools & De Vos, 2010; Schofield & Taylor, 1955). The differences in the pH between that measured in distilled water and measured in 0.01M CaCl2 can reach up to 1 pH unit and depend on soil properties. It is, hence, paramount to specify the method used when reporting a soil pH measurement. Generally, the potential acidity measured in 0.01M CaCl2 is preferred over the pH in water because it excludes the variability caused by weather at the time of sampling, soluble salts and seasonal variability (Richter et al., 1988; Van Lierop, 1981).

In the soil, the cations Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K+ and Na+ are referred to as base cations. Although this terminology is technically contentious, as the cations do not possess any basic properties in their own right. Rather, they are weak Lewis acids. However, these base cations are bound to the negative sites on soil particulates. It is their pH buffering property in the soil upon being exchanged for newly introduced protons (H+) in the soil solution that ‘buffers’ the pH of the soil solution, hence the term base cation (Chadwick & Chorover, 2001). To express the amount of base cations in a forest soil both base cation concentration (cmolc/kg soil) can be measured and expressed as the fractional occupation of the exchangeable base cations (exCa, exMg, exK, exNa) on the effective cation exchange capacity (eCEC), i.e., the base saturation: Base saturation = . If the base saturation is below 15%, Al toxicity can become problematic. A base cation rich soil has become poor when the base saturation tips below 30%, or the pH-0.01M CaCl2 goes below 3.5. The dominant buffer has then become aluminium dissolution over base cation exchange reactions. Forest soils are considered ultra-acidic, i.e. chemically degraded, if in the topsoil the base saturation is below 5% and pH-0.01 M CaCl2 < 3.2.

Aluminium is not a base cation because Al3+ is the strongest Lewis acid in the series of exchangeable cations. If three protons are exchanged for Al3+ , then the pH can still decrease because the exchanged Al3+ is now dissolved and can hydrolyse and decrease pH, i.e., Al3+ +3 H2O ⇒ Al(OH)3 + 3H+. How soil acidification is reflected in distinct buffering pH-ranges depending on the dominant dissolving phase, the so called pH buffer domains, is elucidated in Box 1.

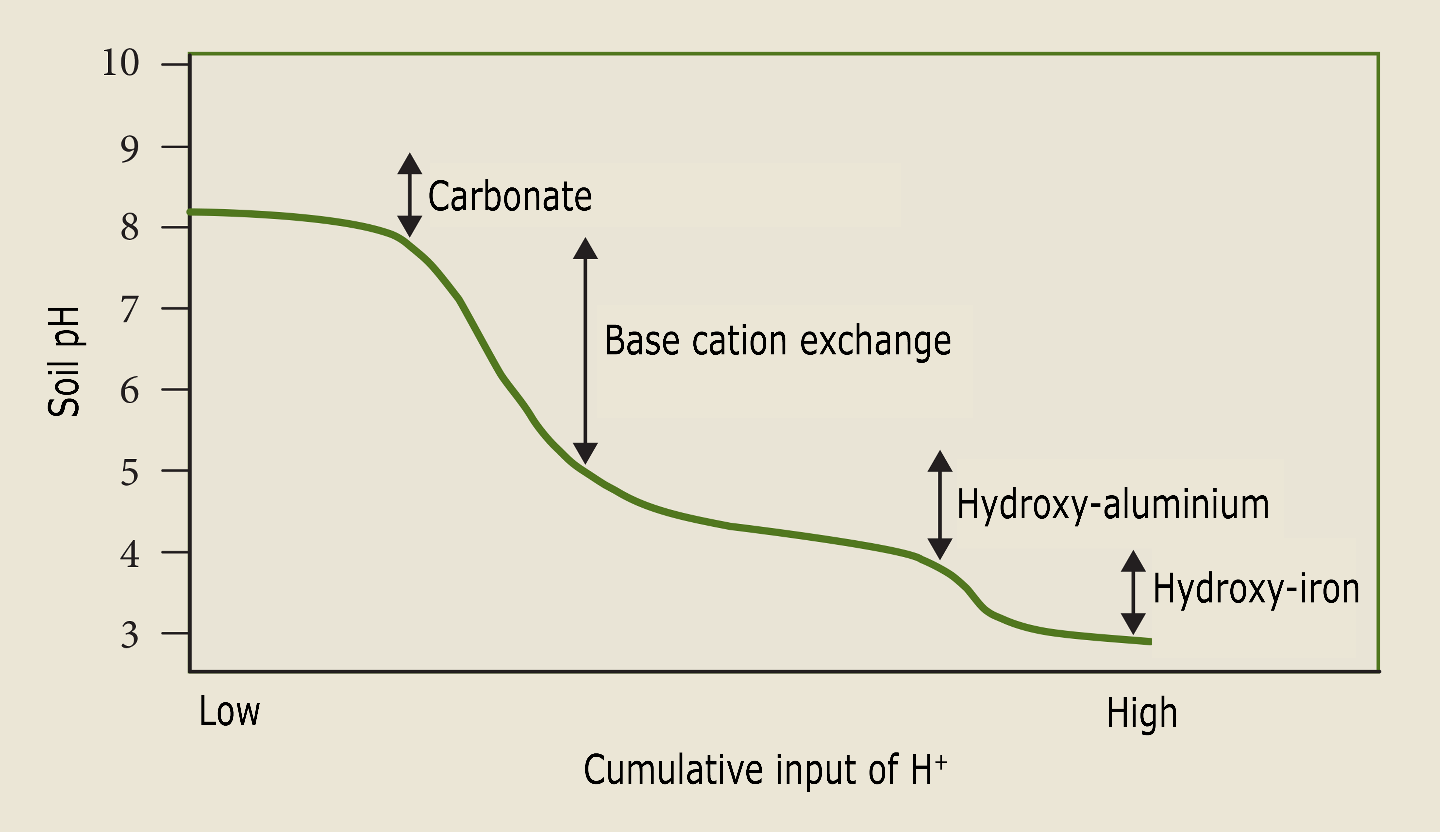

|

Box 48.1 Soil acidification |

|

Soil acidification is primarily an increase in the concentration of hydrogen ions (H+), causing an increase in acidity, but it is also accompanied by a change in the occupation of the exchange complex in the soil, whereby the so-called base cations (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) are displaced by H+ and Al3+. The size of the cation exchange complex in the soil is mainly determined by its clay and loam content and the amount of organic matter. Acidity (pH) is expressed as the negative logarithm of the H+ concentration, and the more acidic the soil, the lower the pH. The buffering capacity of a soil is its resistance to an effective decrease in the pH of the soil solution. Depending on the pH of the soil, different buffer mechanisms take effect. Above pH 6.5, acidity is buffered mainly by the dissolution of calcium carbonate. Below pH 6.5, silicate weathering and exchange of cations with the exchange complex occur. Below pH 4.5, acid inputs are buffered by the dissociation of aluminium and iron oxyhydroxides. The consequences of extensive soil acidification are a reduced availability of base cations and the dissolution of aluminium, which can be toxic to roots. Because of these inherent buffering mechanisms of soil pH, the supply of H+ ions does not immediately lead to a decrease in soil pH, even though soil acidification actually occurs. A sustained supply of acids eventually leads to the depletion of the pH buffering capacity and results in a reduced availability to vegetation of the essential base cations and the dissolution of Al, which is toxic to plant roots. In many soils, leaching of the base cations is faster than replenishment of their reserves by mineral weathering or supply through atmospheric deposition (see Chapter 14). Soil acidification can lead to declines in tree vitality, manifested by leaf discoloration and defoliation, and growth inhibition. There is a higher risk of Al3+ toxicity in forests on richer soils with demanding tree species such as ash and cherry. However, species such as oak, beech and pine exhibit a higher aluminium tolerance. Deep-digging (anecic) and soil-dwelling (endogeic) earthworms disappear from a pH lower than 4 to 4.5 (Muys & Granval, 1997). In many European forest soils, low pH eliminates deep burrowing earthworm species. As a result, litter decomposition rates, and the mixing of humus with mineral soil and soil aeration are limited in these forests, resulting in the accumulation of litter and the formation of a moder or mor humus (see also Chapter 8). Moreover, the disappearance of earthworms can result in increased soil compaction, especially in loamy soils, where biological soil activity is the only significant recovery process. Soil acidification is a natural process in Europe. Precipitation water is naturally slightly acidic due to dissolved carbon dioxide. Moreover, there is a precipitation surplus, so that on soils beyond the reach of groundwater, the leaching of base cations by precipitation exceeds the capillary movement or uptake by vegetation. In calcareous soils, plant respiration causes natural acidification through the formation of carbonic acid in the soil. In acidic soils, however, this is not the case: here, the formation of organic acids by vegetation plays a more important role. Plant growth also causes soil acidification: in order to maintain electron neutrality, the uptake of cations by roots requires the release of H+ , while the uptake of anions is balanced by a flux of OH–, which when present in the soil rapidly reacts with CO2 to form HCO3–. Because plants also take up N as NH4+, nutrient uptake by roots is an acidifying process, but this acidification is not final until the base cations are actually removed from the ecosystem by, for example, wood harvesting. Without this removal, these cations are released again during the decomposition of litter and other organic matter, thus neutralising the H+ previously excreted. The main anthropogenic drivers of soil acidification are the input of SOx, NOx, of which the emissions from burning processes have drastically decreased thanks to air pollution control measures, and acidifying reduced N components (NHx) emitted from livestock production. The carrying capacity of a forest ecosystem against atmospheric depositions is expressed by a critical load. A critical load is the maximum allowable deposition per unit area without – according to current knowledge – causing long-term adverse effects. Various criteria can be used to determine this critical load, such as protection of groundwater, protection of trees from root damage due to aluminium toxicity, loss of biodiversity, preservation of the acid-buffering capacity of the soil, and so on. It is therefore important when using critical loads to indicate the criterion on which they are based.

Figure 48-1-1: Changes in soil pH and buffer domain in the soil as a function of the cumulative input of protons (Bowman et al., 2008). |

The strongest acidification of the topsoil layers occurs in forests with a sandy soil, as sand has a smaller acid buffering capacity than silt or clay.

48.1.2 Brief history of forest nutrient management in Europe

Mineral fertilization is not common in forestry due to cost and environmental considerations, but to increase tree productivity, fertilisation can be applied, much like in agriculture. On the Western-European sand belt, fertilisation was used from the 19th century onwards on a large scale to afforest heathlands on poor sandy soils, which are naturally N-limited and highly sensitive to soil acidification. This fertilisation was aimed, amongst others, at stimulating growth in newly established, young forests and reduce susceptibility to infestation. NPK additions have been a routine silvicultural operation in commercial forests managed for high production, and have mainly been amended and studied in the US and Scandinavia, i.e., in sites suffering less from atmospheric N deposition.

Also rich-litter tree species can be used to improve poor soils. For example, the exotic black cherry (P. serotina), was mixed since around 1850 in P. sylvestris stands in large parts of the Netherlands and Flanders for their ability to increase soil pH (Nyssen et al., 2013). In Germany, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, the poor growth sites of the Black Forest, were limed on a large scale in order to supply Ca and Mg and increase yields (Fiedler et al., 1973). Beginning in the 1980s, large-scale liming followed in large parts of Europe as a remedial measure to address soil acidification and vitality problems caused by air pollution. Scandinavia has a long-term history of amending wood ashes from incineration processes to counteract soil acidification and replenish soil base cation stocks (Augusto et al., 2008). However, the used liming agents (mostly dolomite, sometimes CaO) were often too aggressive when dosed above 3 Mg/ha. Moreover, the amendments had few positive effects on tree growth, and sometimes negative effects on the ecosystem, due to a possible grass proliferation in the herb layer. Indeed, in sandy soils the liming perturbations aggressively raised topsoil pH, thereby boosting litter decomposition, causing worrisome nitrate leaching. Therefore, these measures were discontinued in the Netherlands (Olsthoorn et al., 2006).

Liming with dolomite remains a relatively widely used management measure on loamy substrates in Germany, at e.g. around 2000 ha limed every year in the state of Baden-Württemberg, the amendment is usually about 3 Mg dolomite/ha and reamended every 10 years, if soil tests still reveal a deficiency in base cations. Additionally, wood-ash admixture of 1Mg/ha is advised at more loamy sites to counteract K- and P-deficiency. However, rock phosphates, K2SO4, and rock dusts are also amended to a smaller extent (Hartmann et al., 2024; Janssen et al., 2016). From a circularity point-of-view, Finland still actively applies wood ash in its production forests at doses of 1-3 Mg/ha. With the increased importance of nature conservation in the 2000’s, these potential side effects on understory diversity had become intolerable. As such, and in part due to an often low economic return, targeted nutrient management has received decreased attention at the beginning of the 21st century. Since 2015, interest has sparked in the Netherlands, Belgium, Northern Germany and Poland to supply critically acidified forests with ground igneous rocks, i.e., rock dust. Rock dusts have slow-release liming properties, thereby suffering less from the ecological drawbacks associated with dolomite liming.

Global change drivers put an increasing pressure on our forests, and nutrient management aimed at improving tree vitality could likely be a valuable tool to improve the resilience and resistance of trees to droughts and insect attacks. Therefore, this chapter aims to provide an overview of the management measures through which (bio)geochemical processes can be steered, and the disruptive effect of both acidification and eutrophication can be partly compensated. These can include both direct nutrient applications (see 48.2) or nutrient management through modified forest management (see 48.3).

48.2. Nutrient management through nutrient applications

48.2.1 Concepts of forest nutrition

The nutrient status of forests can be monitored, and if needed, improved by fertilisation, i.e., the application of the nutrients N, P and/or K, and liming, i.e., the addition of acid-neutralising substances. However, it is difficult to determine in what soil concentrations each nutrient should be present for optimal tree growth. This highly depends, among other things, on the specific site characteristics and the tree species. Simple chemical assays can measure the total stock of nutrients present in the soil. However, only a small fraction of these total pools are involved in the yearly nutrient transfers, so these total nutrient stocks may not relate well to the plant available fraction. Moreover, certain nutrients may be present in sufficient quantities, but still be limiting due to antagonistic effects with other nutrients. For example, in N-saturated ecosystems a nutrient deficiency of K or Mg may occur due to the antagonistic effect of excess ammonium (NH4+).

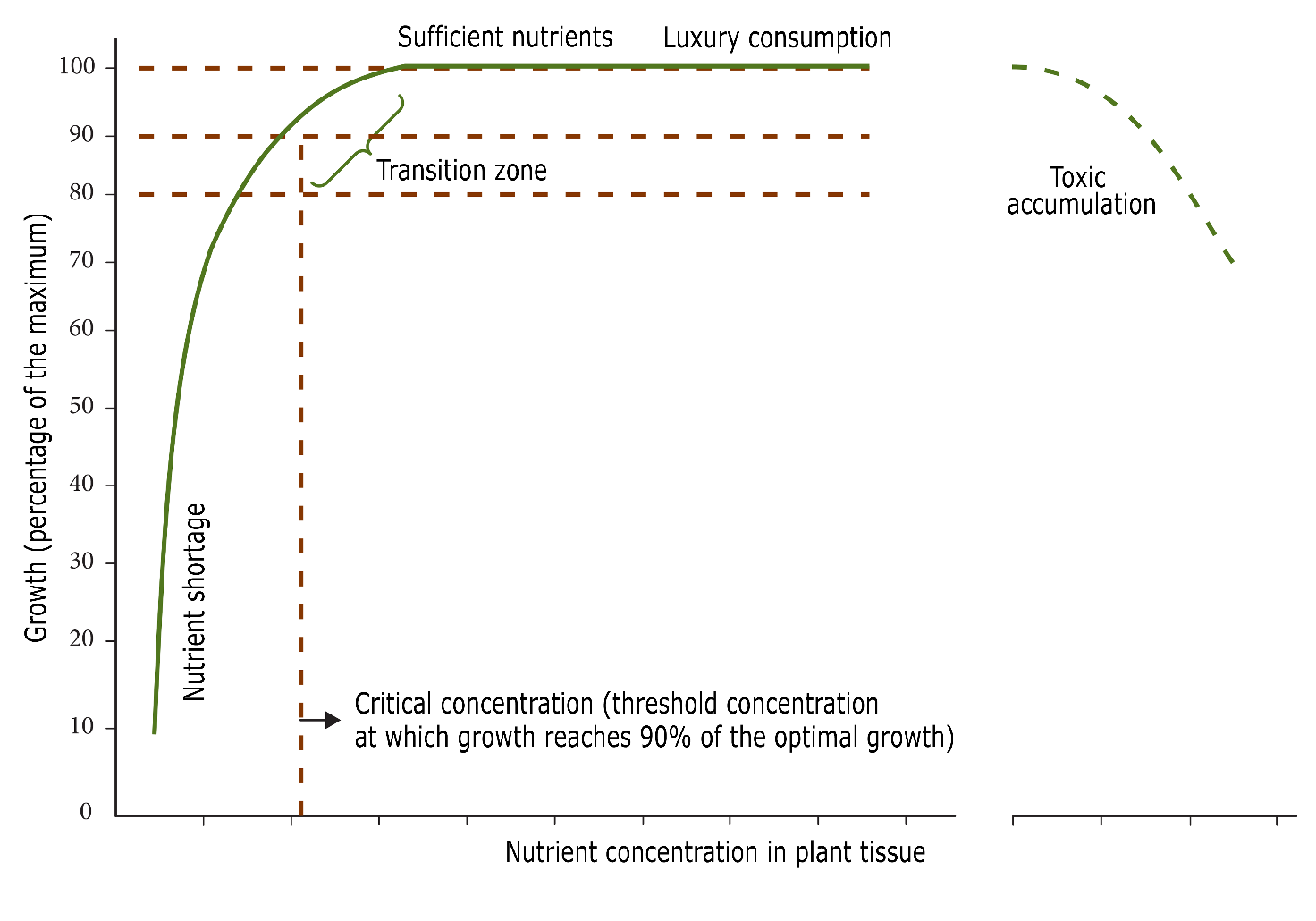

To find out at what nutrient concentrations should be present, empirical relationships can be established between a plant’s growth response after nutrient addition (Figure 48-2). When a nutrient is limiting, an increase in the availability of that nutrient results in a sharp increase in growth, while the concentration in the plant increases only to a limited extent due to dilution into the increased biomass (Marschner, 2012). From the moment that the considered nutrient is available in sufficient concentrations in the soil, however, no increase in growth is observed, but the concentrations in the plant do increase sharply. Furthermore, and according to Liebig’s Law of the Minimum, another nutrient can become limiting from that point onwards. As the nutrient uptake continues without any response in tree growth, it is referred to as luxury consumption, which over time can turn into detrimental concentrations for the plant, again reducing tree growth.

Figure 48-2: Relationship between plant growth and nutrient concentration in tissues. When administration of a particular nutrient increases plant growth but only slightly changes the concentration in the tissues, there is a deficiency of that nutrient. When the same nutrient administration hardly leads to growth increase, but does lead to a stronger increase in nutrient concentration, the plant has sufficient supply of the particular nutrient available. Source: Ulrich & Hills (1967).

Usually, to determine the nutrient status of trees, foliar nutrient concentrations are measured and compared to guideline critical values established for each tree species (Table 48-1). The methodology of foliar analysis is a good diagnostic tool to consider a targeted nutrient amendment and correlates well to other visual metrics such as leaf discoloration and defoliation. Generally, tree vitality and growth also tend to respond immediately to a nutrient amendment that can supply the limiting nutrient. Moreover, foliar analysis is quick, reliable and relatively inexpensive. However, it has a number of drawbacks. For most tree species, critical micronutrient concentrations are not yet well established. Knowledge about the internal variability within the crown and the seasonal variability is essential for using foliage as a means of estimating the nutrient status of trees. After all, both absolute and relative nutrient levels are important to provide definitive information on nutrient availability. The relative nutrient levels are expressed as nutrient ratios of N/Ca, N/Mg, N/K, N/P, for which optimal ranges have also been derived (Mellert & Göttlein, 2012; Van den Burg, 1985).

Table 48-1: Guideline values (g kg-1) for assessing the mineral nutritional status of some tree species (- means not available) (Van Den Burg & Schaap 1995; data for ash are based on Van den Burg, 1974).

|

N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

||

|

Beech |

High |

>28 |

>3.0 |

>8.0 |

– |

>3.0 |

|

Sufficient |

22-28 |

1.5-3.0 |

6.0-8.0 |

≥4.0 |

1.5-3.0 |

|

|

Low |

<22 |

<1.5 |

<6.0 |

<4.0 |

<1.5 |

|

|

Ash |

High |

>28 |

>1.9 |

>15.0 |

– |

>1.9 |

|

Sufficient |

22-28 |

1.5-1.9 |

6.0-15.0 |

– |

– |

|

|

Low |

<22 |

<1.3 |

<6.0 |

– |

– |

|

|

Pedunculate oak |

High |

>28 |

>1.7 |

>8.0 |

>17.0 |

>2.8 |

|

Sufficient |

23-28 |

1.4-1.7 |

6.0-8.0 |

3.0-17.0 |

1.6-2.8 |

|

|

Low |

<23 |

<1.4 |

<6.0 |

<3.0 |

<1.6 |

|

|

Sessile oak |

High |

>28 |

>1.7 |

>8.0 |

– |

>2.8 |

|

Sufficient |

23-28 |

1.3-1.7 |

6.0-8.0 |

3.0-18.0 |

1.5-2.8 |

|

|

Low |

<23 |

<1.3 |

<6.0 |

<3.0 |

<1.5 |

|

|

American oak |

High |

>25 |

>1.7 |

>8.0 |

– |

>2.8 |

|

Sufficient |

21-25 |

1.3-1.7 |

6.0-8.0 |

3.0-18.0 |

1.6-2.8 |

|

|

Low |

<21 |

<1.3 |

<6.0 |

– |

<1.6 |

|

|

Larch |

High |

>25 |

>4.0 |

>15.0 |

– |

>3.0 |

|

Sufficient |

18-25 |

2.0-4.0 |

7.0-15.0 |

≥3.0 |

1.0-3.0 |

|

|

Low |

<18 |

<2.0 |

<7.0 |

(<3.0) |

<1.0 |

|

|

Spruce |

High |

>17 |

>2.0 |

>8.0 |

– |

>1.0 |

|

Sufficient |

13-17 |

1.4-2.0 |

6.0-8.0 |

≥2.0 |

0.7-1.0 |

|

|

Low |

<13 |

<1.4 |

<6.0 |

<2.0 |

<0.7 |

|

|

Corsican pine |

High |

>18 |

>1.6 |

>7.0 |

>1.5 |

>1.0 |

|

Sufficient |

13-18 |

1.3-1.6 |

5.0-7.0 |

1.0-1.5 |

0.6-1.0 |

|

|

Low |

<13 |

<1.3 |

<5.0 |

<1.0 |

<0.6 |

|

|

Scots pine |

High |

>18 |

>1.7 |

>7.0 |

– |

>1.0 |

|

Sufficient |

14-18 |

1.4-1.7 |

5.0-7.0 |

≥1.5 |

0.7-1.0 |

|

|

Low |

<14 |

<1.4 |

<5.0 |

<1.5 |

<0.7 |

|

|

Douglas |

High |

>18 |

>2.2 |

>8.0 |

– |

>1.0 |

|

Sufficient |

14-18 |

1.4-2.2 |

6.0-8.0 |

≥2.5 |

0.7-1.0 |

|

|

Low |

<14 |

<1.4 |

<6.0 |

<2.5 |

<0.7 |

|

48.2.2 Fertilisation and liming

As most trees are N-limited, N fertilization (100-500 kg N/ha) can have an impressive immediate effect on tree growth adding an additional 10 m3/ha within 5 years, but this effect is generally short-lived and reamendments are necessary after 5-10 years. P fertilisation (100-500 kg P/ha) is long-lived and even perceived as increasing the site index, translating in both accelerated tree growth as well as raising the potential dominant height of trees in their growth trajectories. Fertilisation with K-salts can resolve specific K-deficiencies and are ecologically safe below 500 kg K/ha. Decisions about NPK-fertilisation are mostly based on costs and expectations of the return on investment. In forestry, a perennial cropping system, this is hard to calculate. Generally, calculations require intensive fertilisation trials and inherently require uncertainty analysis on the cost of sampling, responsiveness (yes or no), choice of fertilisation (yes or no). In large scale fertilisation schemes the uncertainty is handled by probabilistic decision trees. Ideally, these can be accompanied by an energetic analysis (joules invested versus joules harvested) and carbon footprint analysis (Binkley & Fisher, 2019).

In the 1990’s, fertilisation with N became controversial due to a large portion of forests becoming no longer N-limited due to the high atmospheric N deposition (see Figure 48-1 and Box 48-2 Nitrogen saturation of forest ecosystems). Evidence for disappearing N-limitation is found in the fact that during the past decades increased growth has been observed for Scots pine and beech in European forests (Kahle, 2008). Additionally, from N depositions above 30 kg N/ha/yr onwards, decreases in radial tree growth has been observed (Etzold et al., 2020). The remarkable decline in forest vitality observed several decades ago is probably partly explained by the combined effect of nitrogen deposition and increased evapotranspiration. Intensive monitoring in the European ICP level 2 network found an alarming decreasing nutritional status of P and often of Ca, Mg and K between 1990 and 2010 (Jonard et al., 2015), which was attributed to the higher demand of trees for these nutrients after the growth increase due to anthropogenic N deposition and CO2 fertilisation. Moreover, the active “titration” of forest soils by acidifying deposition has led to drastic decreases in the exchangeable stocks of Ca, Mg and K in the soil. Therefore, the current nutrient management practices in forests are mainly focused on base cation and P nutrient balances.

|

Box 48.2 Nitrogen saturation of forest ecosystems |

|

In addition to soil acidification, the atmospheric supply of N causes a fertilising effect and thereby the removal of N limitation of forests (Etzold et al., 2020). At the beginning of the 20th century, the growth of many forest ecosystems was still limited by the low availability of N. The N cycle of many forest ecosystems was still closed: the supply of N via litterfall and atmospheric deposition was almost completely consumed by the vegetation and/or sequestered in the forest floor, and the leaching of highly mobile NO3– to groundwater would be negligible. N deposition in our forests before industrialization and intensification of agriculture is estimated to be less than 10 kg N ha-1yr-1 (Boxman et al., 1998), which was taken up by trees. The excessive supply of N (> 30 kg N ha-1yr-1) through atmospheric deposition initially accelerates the biogeochemical cycling of N through increased N quantities in foliage, accelerated litter decomposition, and increased uptake of N by plants and microorganisms. However, long-term excessive N deposition reduces the functioning of saprophytic fungi in the soil, leading to decreased litter decomposition and forest floor accumulation (Janssens et al., 2010; Kuyper et al., 2024). As a result, other essential nutrients (P, K, Ca and Mg) or water may eventually become limiting to tree growth. An oversupply of N can cause the forest ecosystem to reach the stage of N saturation (Figure 48-1). At this stage, the capacity of plants and soil to accumulate N is exceeded, causing excess N to leach to groundwater in the form of nitrates and/or be emitted in gaseous form after denitrification (NO, N2O, or finally N2). N saturation therefore implies a permanent change in the functioning of the N cycle: the virtually closed N cycle in N-limited ecosystem turns into an open cycle with significant losses of N. To speak of N saturation, the criterion is that the leaching must exceed 5 kg N ha-1yr-1 and occur throughout the year (Boxman et al., 1998). N deposition also increases the generalist nitrophilous plant species in the understory. A rough generalisation is that herb communities tend to shift to species typical for acidified and high N sites: broad buckler-fern (Dryopteris dilatata) and common blackberry (Rubus spp.) can become dominating. Nitrophilous plants also appear like wavy hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa), purple moorgrass (Molinia caerulea), black nightshade (Solanum nigrum), common chickweed (Stellaria media), common hemp-nettle (Galeopsis tetrahit), and climbing corydalis (Corydalis claviculata) on sandy substrates. On base-poor loamy substrates, N deposition mainly promotes Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) (Muys, 1990; van Breemen and van Dijk, 1988). These plants can overgrow oligotrophic species leading to a loss in species and functional biodiversity. Soil type specific critical loads have therefore been calculated for N depositions (van Dobben et al., 2025). The critical loads for protecting biodiversity in coniferous and deciduous forests on sandy soils are 10 and 15 kg N ha-1yr-1. In 2025, this critical load was still exceeded in more than 60% of European forests.

Figure 48-2-1: Grass proliferation with purple moorgrass (M. caerulea) is a common issue on N-impacted forests on sandy substrates. |

In practice, different types of fertilisers exist that vary in their nutrient content, acid neutralising capacity (degree of neutralisation of H+ ions), solubility (thermodynamic equilibrium) and dissolution rate (kinetics), the latter also highly influenced by grain size. To give a non-exhaustive overview, multiple amendments are listed and ranked for their solubility from high to low, e.g., mineral fertilisers for phosphate (TripleSuperPhosphate > Thomas slag or Ca4(PO4)2 > rock phosphates), potassium (K2SO4 > KCl > wood ash), magnesium (MgSO4 > kieserite MgSO4.H2O > wood ash > dolomite CaMg(CO3)2 > diopside MgCaSi2O6) and liming agents as a source of Ca (quick lime CaO > hydrated lime Ca(OH)2 > wood ash > limestone CaCO3 > dolomite CaMg(CO3)2 > wollastonite CaSiO3 > other aluminosilicate minerals in rock dusts).

In Europe, targeted fertilisation and liming are still used for three reasons. First, it may be aimed at eliminating specific well-known nutrient deficiencies or imbalances. For example, the mineral fertiliser kieserite (MgSO4.H2O) is successfully applied to beech or Norway spruce experiencing loss of vitality due to magnesium deficiency. Magnesium deficiency is visually recognizable by the typical yellow interveinal discoloration in foliage, and occurs on naturally magnesium-poor soils (Bouya et al., 1999). This Mg deficiency is exacerbated on such soils when they are located in the vicinity of intensive livestock farms with high NH3-gas emissions, which, as a result of the antagonism between NH4+ and Mg2+, results in hampered uptake of Mg2+.

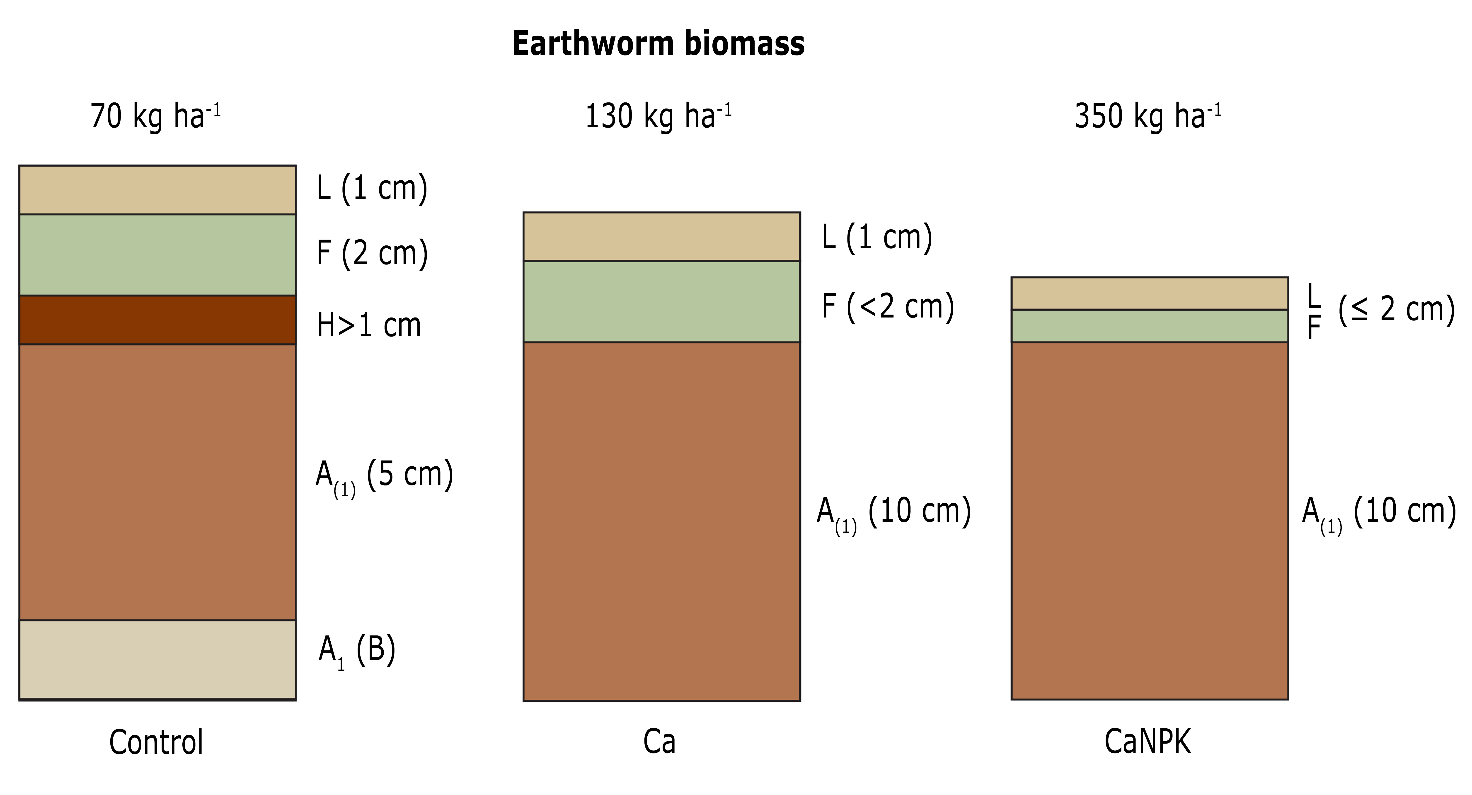

Second, amendments can be applied to compensate for the effects of anthropogenic soil acidification. Liming agents counteract soil acidification and structurally decrease the thickness of the forest floor (ectorganic humus layer) through increased decomposition; the stimulated earthworm bioturbation leads to a thicker organomineral (A) horizon (Siepel et al., 2019). This increases the pH of the topsoil and the stocks of exchangeable Ca2+, Mg2+ and K+ (Figure 48-3). German evaluations after 30 years showed that up to 80% of the amended Ca and Mg could be traced back in the forest floor or upper 40 cm of organomineral soil (Guckland et al., 2012). Liming can disturb soil functioning because it can cause an unusually large boost in soil biological activity in the short term, resulting in an undesirable rapid degradation of the forest floor and release of nitrates. Because of this excess, nitrates may leach out accompanied by cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+and K+ , or aluminium. Consequently, the intended nutrient delivery by liming could offset itself and result in nutrient depletion through leaching and acidification of the top layer of the mineral soil (Kreutzer, 1995).

Figure 48-3: Changes in humus forms and earthworm biomass 10 years after application of fertilisation with Ca, and with Ca, N, P and K in a beech forest on sandstone substrate in Vosges compared with an unfertilized control. Source: Toutain et al. (1988).

Rock dusts are igneous/metamorphic rocks consist of slowly dissolving minerals and their acid-neutralising capacity can slowly buffer the pH, and thereby avoid the drawbacks associated to dolomite liming (Van Der Bauwhede et al., 2024a). Moreover, rock dusts also supply K and P additional to Ca and Mg, which often leads to increased tree growth (Van Der Bauwhede et al., 2024b). Rock dusts can improve foliar nutrition, survival, and growth of saplings when amended in the planting pit of artificial regeneration, certainly when the topsoil has acidified to a pH-0.01M CaCl2 below 3.2 (Van Der Bauwhede et al., 2025). Rock dust applications yield minerals that increase the sorption site density for soil organic matter, therefore they can increase the stocks of organic carbon in the soil. This is an asset of rock dusts compared to liming with wood ash or dolomite. Moreover, rock dusts do not suffer from the ecological drawbacks that are found with faster liming agents and can increase productivity, i.e., the radial growth of trees (see Figure 48-4) (Van Der Bauwhede, 2025).

Figure 48-4: Yearly radial growth of trees expressed as annual Basal Area Increment between 1970-2021 of both control and rock dust amended trees. The amendment of 4.7 tons/ha occurred in 1987 (red line) and consisted of a mixture of basalt and diabase rock dusts. The cored Norway spruce trees were split into two foliar nitrogen classes according to the 10 mg N/g threshold, i.e., the foliar N deficiency threshold. Tree growth barely responded to the rock dust application when N was extremely deficient (left panel, n = 48). But responded markedly to the rock dust application, when the concentration of N in the needles was above this 10 mg N/g threshold (right panel, n = 36). When there was sufficient N, the rock dust could alleviate the other limiting nutrients (Ca, Mg, K) and thereby increase the annual radial growth of trees.

Third, nutrient amendments can be used as part of an integrated soil restoration in which several measures are taken simultaneously to break a vicious cycle of soil degradation. For example, a combination of tree species change with deep-rooting tree species with rich leaf litter (e.g. ash, maple or lime trees) and liming in the plant pit, and possibly the reintroduction of earthworms, can be used to try to restore severely acidified soils (Muys et al., 2003; Van Der Bauwhede et al., 2025). The planting of tree species with rich litter provides opportunities to improve the nutrient cycle in the longer term (Desie et al., 2020b) (see also Chapter 11). However, tree species such as ash and lime are demanding and will not survive planting on severely degraded soils unless a starter fertiliser/ liming (in the plant pit) is given that locally improves soil pH and reduces the availability of Al3+ to the plants (“Fichier écologique des essences,” n.d.). However, this type of integrated ecosystem restoration can only be achieved in a sustainable manner if the earthworm population is also restored, and this way a long-term improvement in humus quality is obtained (Desie et al., 2020a). It is therefore advisable to also introduce deep-digging (anecic) and soil-dwelling (endogeic) earthworms in order to stimulate litter decomposition and enhance bioturbation, thus obtaining a decompacting effect on the soil structure (Muys et al. 2003).

Fertilisers can be spread superficially, by machines (via helicopter, via trucks & blowers or via tractor) or applied into the planting hole. Broadcast application has the disadvantage of altering the entire ecosystem, including the herb layer. However, most applications will have some heterogeneity, assuring local hotspots. This is how habitat diversity remains assured. An addition in the planting hole has the advantage that the nutrients can be used very efficiently by the young tree and that there is no strong development of weeds competing with the young planting.

48.3. Nutrient management through adapted forest management

The nutrient status of forests can also be changed in an indirect way, through forest management. For example, tree species selection, forest edge management, mode and intensity of exploitation, and litter raking all influence nutrient stocks and cycling.

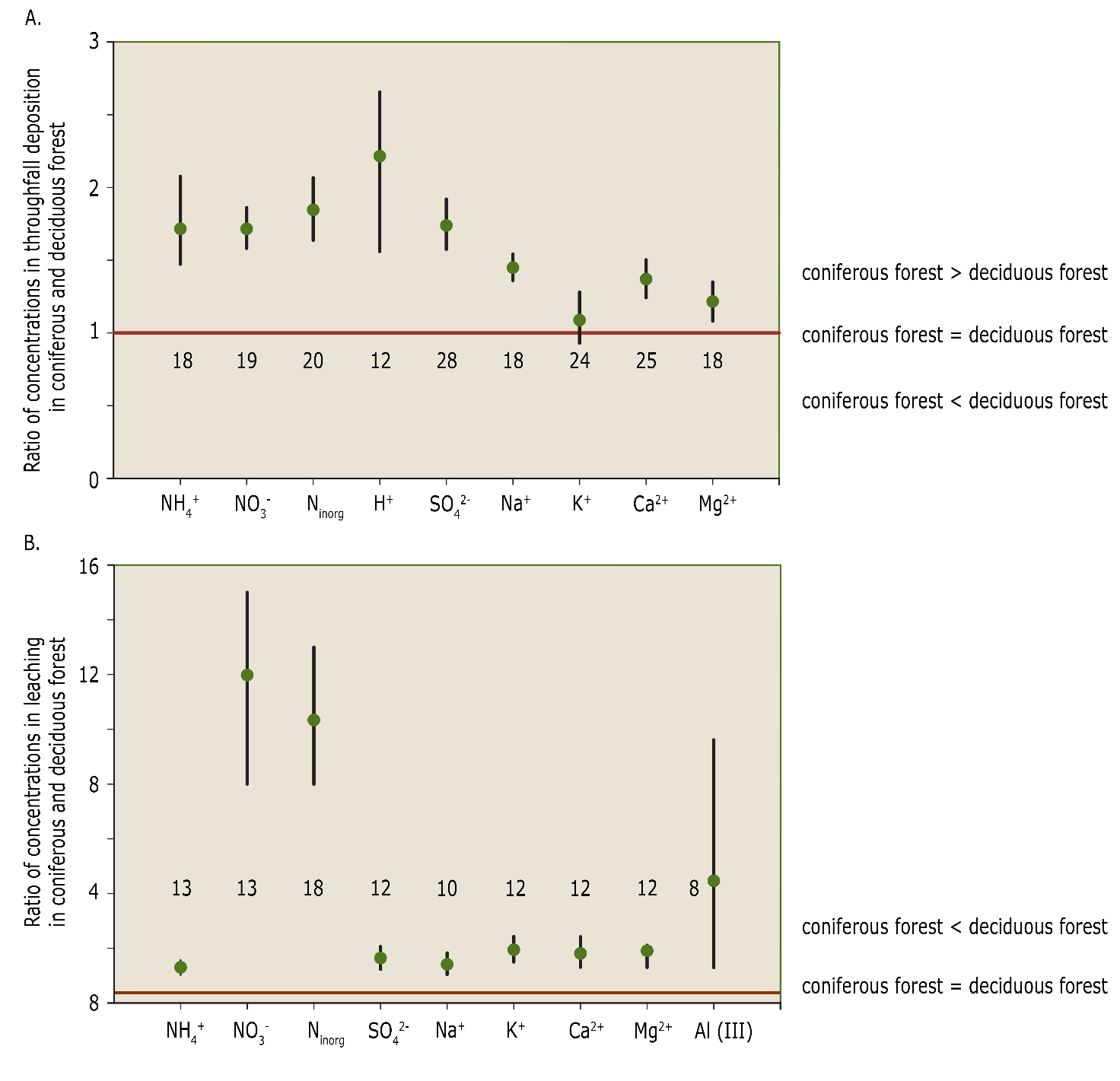

Compared to deciduous trees the evergreen conifers have a larger leaf area index (LAI) and capture deposition throughout the entire year. As a result, in evergreen coniferous forest more N and S are captured and transferred to the forest floor via throughfall water than in deciduous forest (Figure 48-5.A). This additional deposition leads to higher leaching of nitrate, sulphate and base cations (Legout et al., 2016), leading to faster soil acidification and the release of toxic Al3+ into the root environment (Figure 48-5.B). However, litter quality is an even stronger driver of topsoil properties, and if the stand is old enough, stronger even than past land-use or atmospheric deposition (Maes et al., 2019). In general, coniferous species produce litter of poorer quality than deciduous species (see Chapter 11). Overall conifer species and, to a lesser extent, beech and oak are soil acidifying species, while ash, cherry, lime and poplar are soil improving; maple, birch and hornbeam occupy a neutral position (Augusto et al., 2002; Muys & Lust, 1992).

Figure 48-5: Ratios of concentrations (+/- the error bar, as 2 x the standard deviation) of different ions between coniferous forest and deciduous forest in throughfall deposition (A) and leaching (B) in forests in Europe, the United States and Canada. The numbers represent the number of forests included in the analysis. Source: De Schrijver et al. (2007b).

As richer litter quality leads to faster litter decomposition than poor litter, it allows nutrients to circulate faster through the forest ecosystem and thereby reduces soil acidification (Berg and McClaugherty, 2014). In N-limited forests, species could traditionally be ranked for their litter quality based on the C/N ratio, whereas a high C/N ratio indicated lower quality and a lower C/N ratio indicated a higher quality. Moreover, litter decomposition rates are also steered by C quality, with fast decomposing C being accessible C compounds (non-structural carbohydrates, phenolics), while slow decomposing are the recalcitrant C compounds (condensed tannins, lignin) (Hättenschwiler & Jørgensen, 2010).

However, in N-saturated forests a better predictor of litter decomposition and therefore soil acidification is the total base cation concentration in the foliage. These concentrations allow ranking the common European tree species from rich to poor litter; rich: P. avium > P. padus > Fraxinus species > Tilia species > A. incana , moderate: Acer species > B. pendula; poor: Quercus species > F. sylvatica > P. menziesii > Pinus species > Picea species (Desie et al., 2020b).

Rich litter tree species can increase soil pH and base saturation, and therefore reverse some of the effects of acidifying homogeneous coniferous stands upon admixture of rich litter species (Desie et al., 2023). On more fertile soils, for example, those with a higher loam or clay fraction or on former agricultural soils, incorporating rich litter species is an important management option in view of safeguarding soil fertility ((Hommel et al., 2007). Figure 48-6 shows the long-term effect on forest floor formation after afforestation of grasslands with rich litter versus poor litter species.

Figure 48-6: The effect of tree species on humus development, 20 years after planting on a former pasture. pH = acidity, V = base saturation, EPI = biomass epigeic earthworms, ENDO = biomass endogeic earthworms, ANEC = biomass anecic earthworms, TPRO = total earthworm biomass; all earthworm quantities are expressed in kg fresh weight ha-1. Source: Muys et al. (1992).

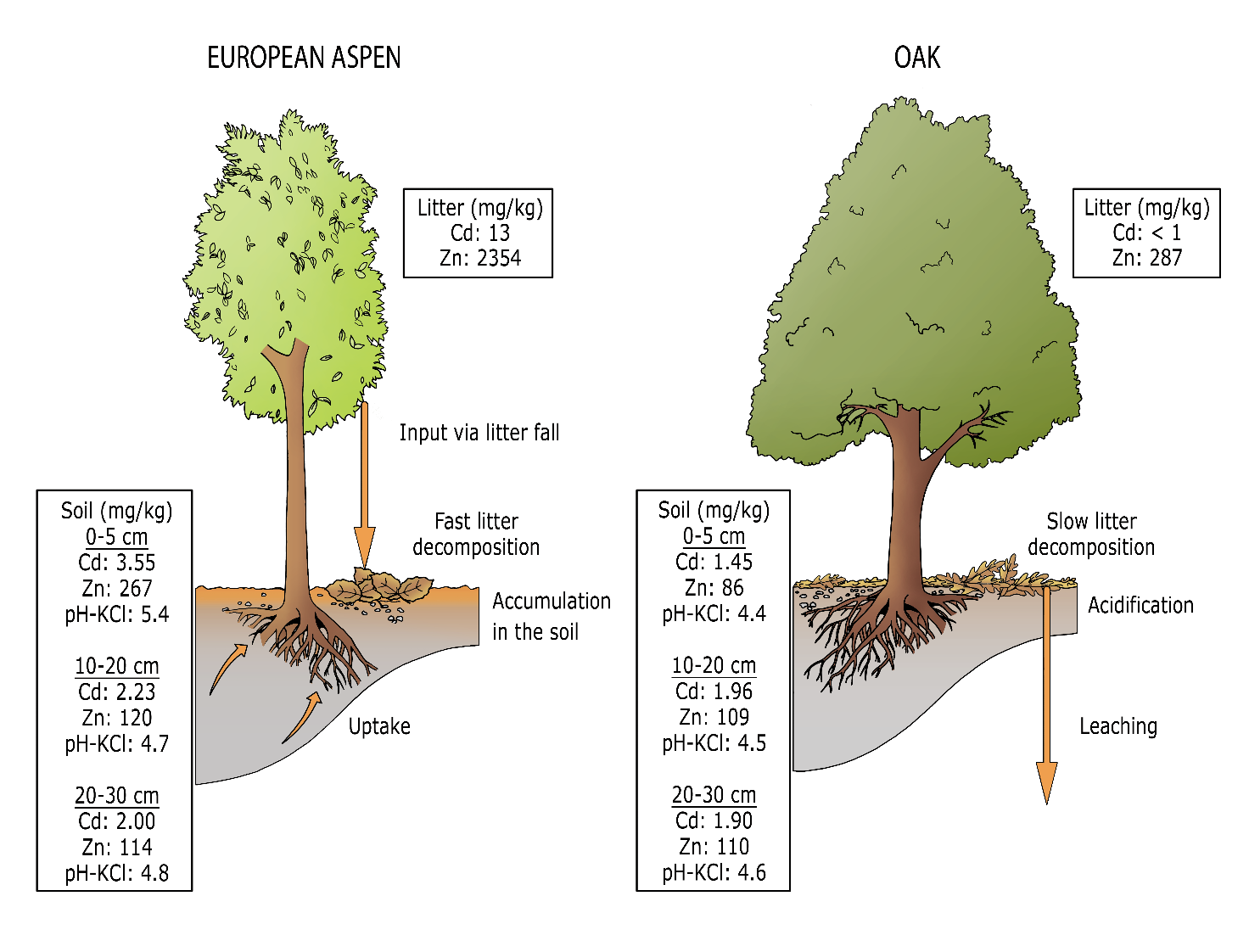

On heavy metal-contaminated soils, the distribution of metals in the aboveground biomass, litter layer and mineral soil depends greatly on the tree species. For example, birch accumulates Zn, and poplar and willow absorb Cd and Zn from the soil and store it in their foliage. In this way, the metals are taken up from the different soil layers and end up in the topsoil layer via the returning leaf litter, so that a planting of these species poses a risk of dispersion of Cd and Zn in the ecosystem and redistribution of these heavy metals in the soil (see Figure 48-7). Topsoils under poplar and willow are often highly enriched with Cd and Zn, which is detrimental to both soil fauna and micro-organisms, meaning these species should be avoided in phytostabilisation projects (Mertens et al., 2007), see Box 48.3. Phytoremediation. In contrast, soil acidifying tree species such as coniferous species, beech and oak can increase the mobility of metals in the soil, allowing them to leach into groundwater. When afforesting contaminated soils for land reclamation purposes, it is therefore important to mix soil acidifying tree species with soil improving species such as ash, cherry and linden.

Figure 48-7: Sketch of the different processes occurring in phytostabilisation, for two extreme situations: European aspen versus oak. Orange indicates the fluxes and stocks of cadmium and zinc, with uptake and accumulation in the topsoil layer occurring mainly in European aspen and much less in oak. Average Cd and Zn concentrations (mg kg DS-1) in the litter and in the different soil layers, and the average pH-KCl after 10 years of tree growth in the Waaltjesbos at Lommel (Van Nevel et al. 2010).

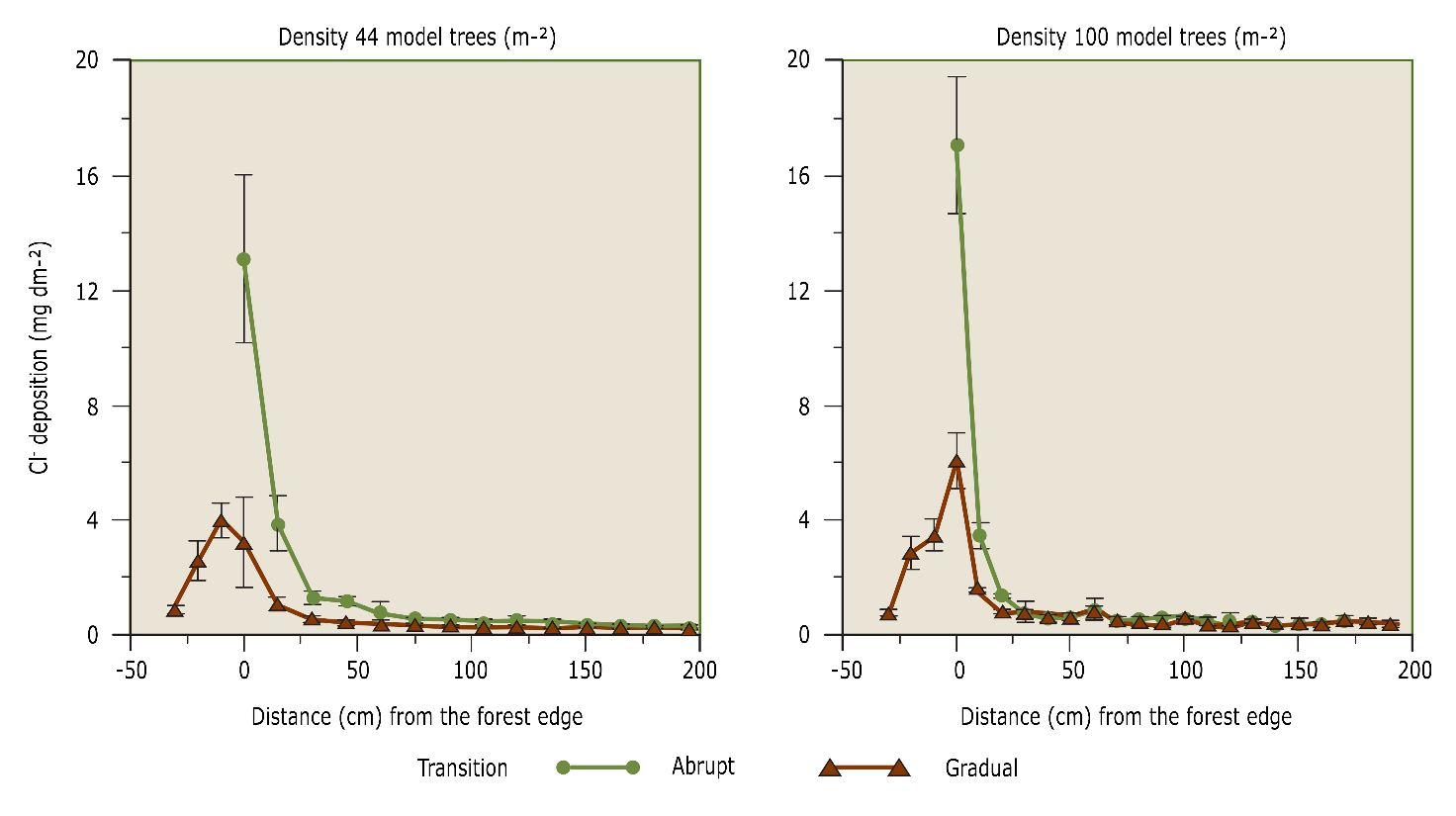

Forest edges capture additional elements from the atmosphere via dry deposition relative to the forest behind them, the forest core, yielding the risk of additional acidification and eutrophication (De Schrijver et al. 1998). The abrupt transition from open terrain to forest causes higher wind speeds and stronger air turbulence to occur at the forest edge than in the forest core. As a result, atmospheric deposition in an edge zone of 50 m deep can be up to 2.5 times higher than in the forest core (De Schrijver et al., 2007). The zone of increased deposition can take up to 100 m. The depth of penetration and deposition increases differ for each nutrient and depend on the tree species and the structure and shape of the forest edge. For example, in deciduous forests, both the penetration depth and the deposition increase are smaller than in coniferous forests (Wuyts et al., 2008a). A dense forest edge also makes nutrients penetrate less deep into the forest, while in less dense forests the extent at which deposition increases at the edge will be limited (Wuyts et al., 2008b). A gradually rising forest edge vegetation via a mantle and hem vegetation (see Figure 48-8) reduces the deposition increase at the edge and/or the penetration depth (Wuyts et al., 2009). A forest edge vegetation that transitions smoothly thus leads to a reduced deposition of nutrients in the forest core and consequently lowers the risk of acidification and eutrophication.

Figure 48-8: Dry deposition of Cl–(chloride) along a transect running from the forest edge to the stock in the case of an abrupt sharp forest edge and in the case of a gradual forest edge with mantle and hem vegetation. Measurements were made on a 1:100 scale model forest in a wind tunnel. Source: Wuyts et al. (2008b).

Due to the high degree of fragmentation of the European forested area, a large proportion of the forest area consists of forest edges. Forest edge management by appropriate tree species selection and establishment or spontaneous development of vegetation at existing forest edges can in fact contribute significantly to reducing atmospheric depositions and thus acidification and eutrophication.

48.3.3 Method of exploitation and forest nutrient balances

In the long-term, nutrient management and additions should not compromise the stability and sustainability. Next to nutrient leaching, the methods of forest exploitation (and the rotation times) are an important contributor to possible nutrient outputs from the forest ecosystem. Moreover, the most important source of Ca, Mg, K and P in a forest, additionally to mineral weathering, is mainly atmospheric deposition of dissolved salts and dust. Therefore, the net effect of acidifying N and S depositions on base cation leaching is often cancelled out, with this effect being greater on sites near the ocean or near to active mines.

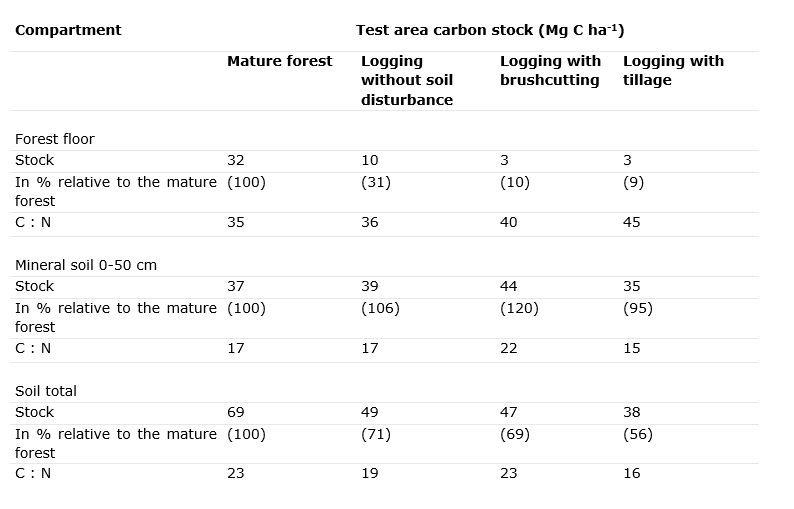

Felling a stand leads to accelerated decomposition and mineralisation of the forest floor and organic matter present due to increased irradiation. Moreover, the branch wood remaining behind and the root systems in the soil are an additional source of mineralizable organic matter. When little soil vegetation is present after felling to reabsorb the released nutrients (such as NO3– and Ca2+), they can leach into groundwater (Legout et al., 2009). Thus, clearcutting systems in particular periodically cause accelerated leaching of nutrients from the system. Nutrient loss during clearcutting is exacerbated if the soil is additionally tilled (or ploughed, see Table 48-2). With more careful natural regeneration, by group felling with small groups (< 0.1 ha), the nutrient losses are smaller because fewer nutrients are suddenly released and/or vegetation is still present that can absorb the released nutrients.

Table 48-2: Total stocks of C (Mg ha-1) in the forest floor of a Scots pine forest before and after clearcutting without soil disturbance, after brushcutting and after tillage. Source: Burschel et al. (1977).

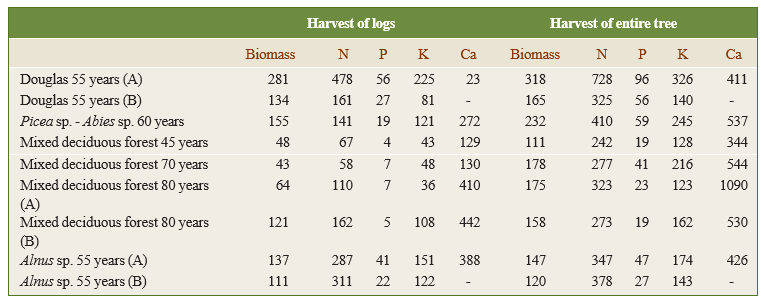

The types of management can be ranked based on decreasing nutrient removal and therefore increasing sustainability: clearcut < whole-tree-harvest < stem-only-harvest < wood-only-harvest (with on-site bark-stripping). Removing only stemwood causes significantly less nutrient loss than harvesting the entire tree because both branch wood and leaves represent a significant proportion of the total nutrient supply (Table 48-3). Because young trees generally have a relatively more nutrient-rich bark and sapwood than heartwood in the trunk compared to old trees and increased leaching, a shortening of the rotation length leads to increased nutrient removal from the ecosystem.

Table 48-3: Biomass (Mg ha-1) and nutrient removal (kg ha-1) after harvest of stemwood only versus harvest of the entire aboveground tree biomass, comparing rich (A) and poor (B) soils in the United States (- : not determined). Source: Mann et al. (1988).

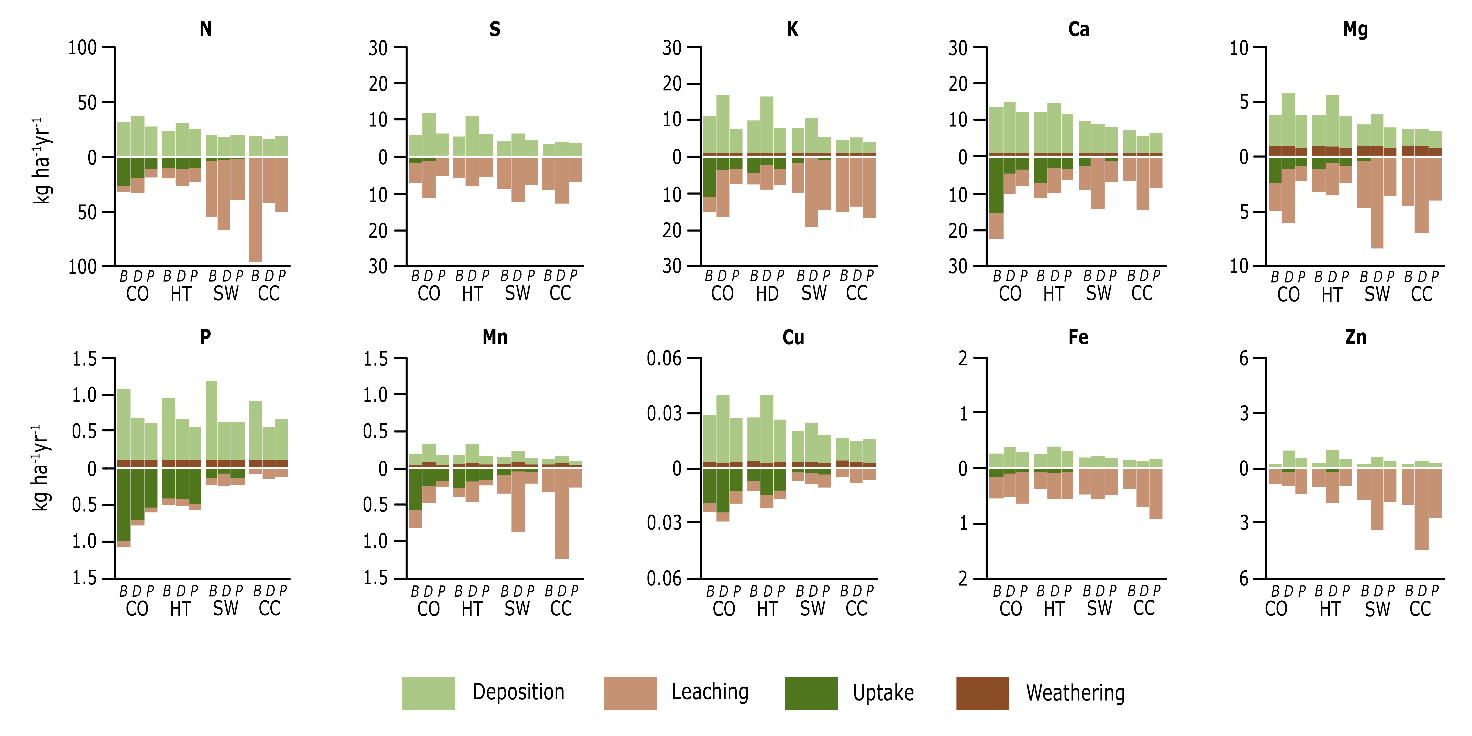

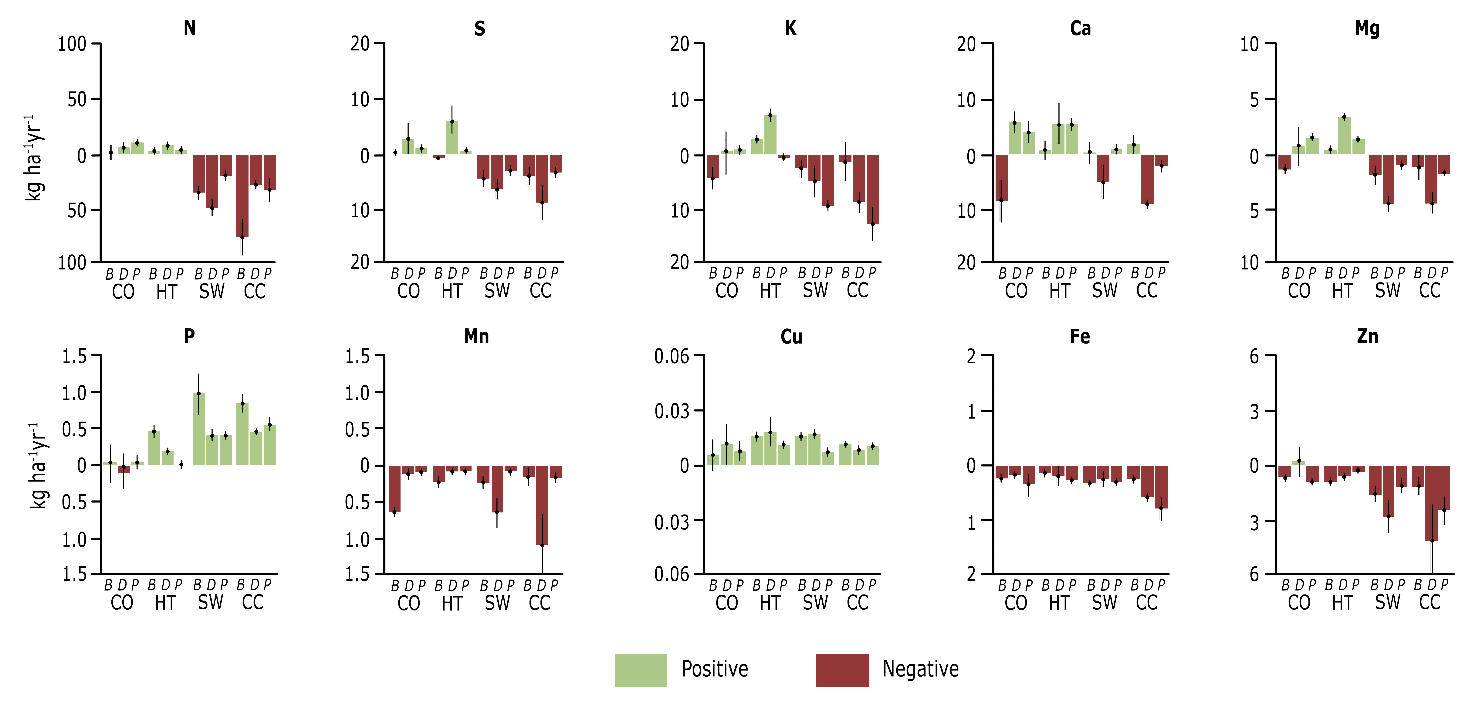

The exploitation types also greatly affect the balance between inputs and outputs of nutrients. For example, more nutrients are lost in a clearcut (100% removed) or shelterwood cutting (80% removed) than in a high thinning (20% removed) (Figure 48-9) (Vos et al., 2023). Mostly in N-impacted base cation poor forests on sandy soils, i.e., sites where the nutrient balance is easily negative, preserving canopy cover and minimizing biomass export are key practices for nutrient conservation, as the nutrient balances can easily become negative when harvesting larger amounts of wood (Figure 48-10). However, debarking and maximized retention of branchwood are vital measures to keep the nutrient balance positive in all forests (Ahrends et al., 2022).

Figure 48-9: Nutrient balance case study in the Netherlands of beech (B), Douglas fir (D), or Scots pine (P) in the second year after timber harvesting, including atmospheric deposition and estimated chemical weathering of the soil as nutrient input fluxes, and nutrient uptake by the forest and leaching as nutrient removal fluxes. For each nutrient, the balance of the control plot (CO, 0% cut) of beech, Douglas fir and Scots pine is given first, followed by the balances of the high thinning (HT, 20% cut), shelterwood (SW, 80% cut) and clearcutting (CC, 100% cut) for the same three tree species (BDP).

Figure 48-10: The net balances of macro- and micronutrients derived from Figure 48-9, whereby the nutrient supply (deposition and weathering) is reduced by the nutrient removal (uptake by trees and leaching). A negative balance means that the removal is greater than the supply, causing the soil supply of that nutrient to decrease. Positive balances cause an increase in the soil supply and indicate that the forest is functioning sustainably. Shelterwood systems (80% cut) and clearcuts are detrimental to the nutrient balance of Ca, Mg, K, and Mn and can therefore exacerbate the effects of soil acidification on the forest ecosystem.

48.3.4 Ploughing and litter raking

Sodcutting is the removal of the topsoil layer (usually less than 5 cm) and associated vegetation. Sodcutting was a common practice on heathlands in western Europe, as a source of nutrients in agriculture before mineral fertilizers appeared on the market. In forests, litter raking was predominant, i.e., the removal of the layer of undecomposed leaf litter. The sods and raked litter were first used for animal bedding in the potting shed, and subsequently when loaded with manure used as a fertiliser in agricultural fields (the infields). These practices were carried out until the mid-20th century (Van Goor 1952), and led to severe soil impoverishment and acidification in many European forests. The loss of N, C, P and base cations depended on the frequency and duration of litter removal, soil type and tree species. On average, the available nutrient stock in the soil decreased by 5-78% N and by 42% for K, 57% for Ca, 52% for Mg and 45% for P (Sayer, 2006). Now that this use has been abandoned, a thick forest floor of decomposing litter has again developed on many poor sandy soils. Such forests have a mor or mormoder humus form (see Chapters 8 and 11) in which large stocks of nutrients are immobilised. In N-saturated forests, the removal of the forest floor is sometimes proposed to lower the N stock in the soil, improving the nutritional status of trees and limiting nitrate leaching (Prietzel & Kaiser, 2005). In an experiment in a poor coniferous forest on sandy soil (Boxman and Roelofs, 2006), 2400 kg N/ha were removed by raking the forest floor, but also large amounts of other essential nutrients, including 40 kg K, 200 kg Ca, 30 kg Mg and 50 kg P. In addition to a strong decrease in nutrient availability, litter removal to curb N-saturation results in a strong and long-term decrease in carbon content (also in the deeper soil layers), accelerated podzolization, a decrease in site index and lower needle production. Litter raking thus poses a direct threat to the biogeochemical and thus also the ecological functioning of a forest ecosystem.

Ahrends, B., von Wilpert, K., Weis, W., Vonderach, C., Kändler, G., Zirlewagen, D., Sucker, C., Puhlmann, H., 2022. Merits and Limitations of Element Balances as a Forest Planning Tool for Harvest Intensities and Sustainable Nutrient Management—A Case Study from Germany. Soil Systems 6, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems6020041

Augusto, L., Bakker, M.R., Meredieu, C., 2008. Wood ash applications to temperate forest ecosystems—potential benefits and drawbacks. Plant Soil 306, 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9570-z

Augusto, L., Ranger, J., Binkley, D., Rothe, A., 2002. Impact of several common tree species of European temperate forests on soil fertility. Ann. For. Sci. 59, 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1051/forest:2002020

Baule, H., Fricker, C., 1967. Die Düngung von Waldbäumen. Bayerischer Landwirtschaftsverlag Gmbh, München.

Berg, B., McClaugherty, C., 2014. Plant Litter: Decomposition, Humus Formation, Carbon Sequestration. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38821-7

Binkley, D., Fisher, R.F., 2019. Ecology and Management of Forest Soils. John Wiley & Sons.

Bouya, D., Myttenaere, C., Weissen, F., Van Praag, H.J., 1999. Needle Permeability of Norway Spruce (picea Abies (l.) Karst.) as Influenced by Magnesium Nutrition. Belgian Journal of Botany 132, 105–118.

Boxman, A.W., Roelofs, J.G.M., 2006. Effects of liming, sod-cutting and fertilization at ambient and decreased nitrogen deposition on the soil solution chemistry in a Scots pine forest in the Netherlands. Forest Ecology and Management 237, 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2006.09.050

Boxman, A.W., van der Ven, P.J.M., Roelofs, J.G.M., 1998. Ecosystem recovery after a decrease in nitrogen input to a Scots pine stand at Ysselsteyn, the Netherlands. Forest Ecology and Management, The Whole Ecosystem Experiments of the NITREX and EXMAN Projects 101, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00132-1

Chadwick, O.A., Chorover, J., 2001. The chemistry of pedogenic thresholds. Geoderma, Developments and Trends in Soil Science 100, 321–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7061(01)00027-1

Cools, N., De Vos, B., 2010. Sampling and analysis of soil. Manual part X. Manual on methods and criteria for harmonized sampling, assessment, monitoring and analysis of the effects of air pollution on forests. UNECE, ICP Forests, Hamburg 208.

De Schrijver, A., Devlaeminck, R., Mertens, J., Wuyts, K., Hermy, M., Verheyen, K., 2007. On the importance of incorporating forest edge deposition for evaluating exceedance of critical pollutant loads. Applied Vegetation Science 10, 293–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-109X.2007.tb00529.x

Desie, E., Muys, B., den Ouden, J., Nyssen, B., Sousa-Silva, R., van den Berg, L., van den Burg, A., van Duinen, G.-J., Van Meerbeek, K., Weijters, M., Vancampenhout, K., 2023. Impact of black cherry on pedunculate oak vitality in mixed forests: Balancing benefits and concerns. Forest Ecosystems 10, 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fecs.2023.100148

Desie, E., Van Meerbeek, K., De Wandeler, H., Bruelheide, H., Domisch, T., Jaroszewicz, B., Joly, F.-X., Vancampenhout, K., Vesterdal, L., Muys, B., 2020a. Positive feedback loop between earthworms, humus form and soil pH reinforces earthworm abundance in European forests. Functional Ecology 34, 2598–2610. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13668

Desie, E., Vancampenhout, K., Nyssen, B., van den Berg, L., Weijters, M., van Duinen, G.-J., den Ouden, J., Van Meerbeek, K., Muys, B., 2020b. Litter quality and the law of the most limiting: Opportunities for restoring nutrient cycles in acidified forest soils. Science of The Total Environment 699, 134383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134383

Etzold, S., Ferretti, M., Reinds, G.J., Solberg, S., Gessler, A., Waldner, P., Schaub, M., Simpson, D., Benham, S., Hansen, K., Ingerslev, M., Jonard, M., Karlsson, P.E., Lindroos, A.-J., Marchetto, A., Manninger, M., Meesenburg, H., Merilä, P., Nöjd, P., Rautio, P., Sanders, T.G.M., Seidling, W., Skudnik, M., Thimonier, A., Verstraeten, A., Vesterdal, L., Vejpustkova, M., de Vries, W., 2020. Nitrogen deposition is the most important environmental driver of growth of pure, even-aged and managed European forests. Forest Ecology and Management 458, 117762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117762

Fichier écologique des essences [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.fichierecologique.be/#!/ (accessed 10.8.24).

Fiedler, H.J., Hoffmann, F., Nebe, W., 1973. Forstliche Pflanzenernährung und Düngung. Stuttgart: Gustave Fischer Verlag.

Guckland, A., Ahrends, B., Paar, U., Dammann, I., Evers, J., Meiwes, K.J., Schönfelder, E., Ullrich, T., Mindrup, M., König, N., Eichhorn, J., 2012. Predicting depth translocation of base cations after forest liming: results from long-term experiments. Eur J Forest Res 131, 1869–1887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-012-0639-0

Hartmann, P., Jansone, L., Mahlau, L., Maier, M., Lang, V., Puhlmann, H., 2024. Liming leads to changes in the physical properties of acidified forest soils. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 187, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.202300055

Hättenschwiler, S., Jørgensen, H.B., 2010. Carbon quality rather than stoichiometry controls litter decomposition in a tropical rain forest. Journal of Ecology 98, 754–763. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01671.x

Hommel, P.W.F.M., Waal, R.W. de, Muys, B., Ouden, J. den, Spek, T., 2007. Terug naar het lindewoud : strooiselkwaliteit als basis voor ecologisch bosbeheer. KNVV Uitgeverij, Zeist.

Janssen, A., Schäffer, J., Wilpert, K., Reif, A., 2016. Extent of forest liming in Baden-Wurttemberg 15, 5–15.

Janssens, I.A., Dieleman, W., Luyssaert, S., Subke, J.-A., Reichstein, M., Ceulemans, R., Ciais, P., Dolman, A.J., Grace, J., Matteucci, G., Papale, D., Piao, S.L., Schulze, E.-D., Tang, J., Law, B.E., 2010. Reduction of forest soil respiration in response to nitrogen deposition. Nature Geosci 3, 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo844

Jonard, M., Fürst, A., Verstraeten, A., Thimonier, A., Timmermann, V., Potočić, N., Waldner, P., Benham, S., Hansen, K., Merilä, P., Ponette, Q., de la Cruz, A.C., Roskams, P., Nicolas, M., Croisé, L., Ingerslev, M., Matteucci, G., Decinti, B., Bascietto, M., Rautio, P., 2015. Tree mineral nutrition is deteriorating in Europe. Global Change Biology 21, 418–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12657

Kahle, H.-P. (Ed.), 2008. Causes and Consequences of Forest Growth Trends in Europe. Brill.

Kuyper, T.W., Janssens, I.A., Vicca, S., 2024. Chapter 8 – Impacts of nitrogen deposition on litter and soil carbon dynamics in forests, in: Du, E., de Vries, W. (Eds.), Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition to Global Forests. Academic Press, pp. 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91140-5.00012-9

Legout, A., Nys, C., Picard, J.-F., Turpault, M.-P., Dambrine, E., 2009. Effects of storm Lothar (1999) on the chemical composition of soil solutions and on herbaceous cover, humus and soils (Fougères, France). Forest Ecology and Management 257, 800–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.10.012

Legout, A., van der Heijden, G., Jaffrain, J., Boudot, J.-P., Ranger, J., 2016. Tree species effects on solution chemistry and major element fluxes: A case study in the Morvan (Breuil, France). Forest Ecology and Management 378, 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.07.003

Maes, S.L., Blondeel, H., Perring, M.P., Depauw, L., Brūmelis, G., Brunet, J., Decocq, G., den Ouden, J., Härdtle, W., Hédl, R., Heinken, T., Heinrichs, S., Jaroszewicz, B., Kirby, K., Kopecký, M., Máliš, F., Wulf, M., Verheyen, K., 2019. Litter quality, land-use history, and nitrogen deposition effects on topsoil conditions across European temperate deciduous forests. Forest Ecology and Management 433, 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.10.056

Marschner, P., 2012. Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants, 3rd ed. ed. Academic Press, Amsterdam ;

Mellert, K.H., Göttlein, A., 2012. Comparison of new foliar nutrient thresholds derived from van den Burg’s literature compilation with established central European references. Eur J Forest Res 131, 1461–1472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-012-0615-8

Mertens, J., Van Nevel, L., De Schrijver, A., Piesschaert, F., Oosterbaan, A., Tack, F.M.G., Verheyen, K., 2007. Tree species effect on the redistribution of soil metals. Environmental Pollution 149, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.01.002

Muys, B., 1990. N excess in the forest: effects and possible meausures. Silva Gandavensis 55. https://doi.org/10.21825/sg.v55i0.899

Muys, B., Beckers, G., Nachtergale, L., Lust, N., Merckx, R., Granval, P., 2003. Medium-term evaluation of a forest soil restoration trial combining tree species change, fertilisation and earthworm introduction: The 7th international symposium on earthworm ecology · Cardiff · Wales · 2002. Pedobiologia 47, 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1078/0031-4056-00257

Muys, B., Granval, Ph., 1997. Earthworms as bio-indicators of forest site quality. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 5th International Symposium on Earthworm Ecology 29, 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(96)00047-8

Muys, B., Lust, N., 1992. Inventory of the earthworm communities and the state of litter decomposition in the forests of flanders, belgium, and its implications for forest management. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 24, 1677–1681. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(92)90169-X

Nyssen, B., den Ouden, J., Verheyen, K., 2013. Amerikaanse vogelkers Van bospest tot bosboom. KNNV Uitgeverij; Zeist.

Olsthoorn, A.F.M., van den Berg, C.A., de Gruijter, J.J., 2006. Evaluatie van bemesting en bekalking in bossen en de ontwikkeling in onbehandelde bossen. Evaluatie Effectgerichte Maatregelen (EGM) in multifunctionele bossen 39.

Prietzel, J., Kaiser, K.O., 2005. De-eutrophication of a nitrogen-saturated Scots pine forest by prescribed litter-raking. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 168, 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200421705

Sayer, E.J., 2006. Using experimental manipulation to assess the roles of leaf litter in the functioning of forest ecosystems. Biological Reviews 81, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006846

Schofield, R.K., Taylor, A.W., 1955. The Measurement of Soil pH. Soil Science Society of America Journal 19, 164–167. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1955.03615995001900020013x

Siepel, H., Bobbink, R., van de Riet, B.P., van den Burg, A.B., Jongejans, E., 2019. Long-term effects of liming on soil physico-chemical properties and micro-arthropod communities in Scotch pine forest. Biol Fertil Soils 55, 675–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-019-01378-3

Ulrich, B., Sumner, M.E., 2012. Soil Acidity. Springer Science & Business Media.

van Breemen, N., van Dijk, H.F.G., 1988. Ecosystem effects of atmospheric deposition of nitrogen in The Netherlands. Environmental Pollution, Excess Nitrogen Deposition 54, 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/0269-7491(88)90115-7

Van den Burg, J., 1985. Foliar analysis for determination of tree nutrient status: a compilation of literature data, = Overzicht van blad- en naaldanalyses voor de beoordeling van de minerale voedingstoestand van bomen : een samenvoeging van literatuurgegevens, Rijksinstituut voor onderzoek in de bos- en landschapsbouw De Dorschkamp. Rapport 414. Rijksinstituut voor onderzoek in de bos- en landschapsbouw De Dorschkamp, Wageningen.

Van Der Bauwhede, R., 2025. Rock dust as a restoration measure for acidified forests. From mineral dissolution to helicopter application. KU Leuven, Leuven. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.27736.20487

Van Der Bauwhede, R., Muys, B., Vancampenhout, K., Smolders, E., 2024a. Accelerated weathering of silicate rock dusts predicts the slow-release liming in soils depending on rock mineralogy, soil acidity, and test methodology. Geoderma 441, 116734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116734

Van Der Bauwhede, R., Troonbeeckx, J., Serbest, I., Moens, C., Desie, E., Katzensteiner, K., Vancampenhout, K., Smolders, E., Muys, B., 2024b. Restoration rocks: The long-term impact of rock dust application on soil, tree foliar nutrition, tree radial growth, and understory biodiversity in Norway spruce forest stands. Forest Ecology and Management 568, 122109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.122109

Van Der Bauwhede, R., van den Berg, L., Vancampenhout, K., Smolders, E., Muys, B., 2025. Field phytometers and lab tests demonstrate that rock dust can outperform dolomite and fertilisers for acid forest soil restoration. Plant Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-024-07175-8

van Dobben, H.F., Wamelink, G.W.W., Bobbink, R., Roelofsen, H.D., 2025. Revision of nitrogen critical loads for Natura 2000 Habitat types in The Netherlands. Science of The Total Environment 974, 179203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179203

Vos, M.A.E., den Ouden, J., Hoosbeek, M., Valtera, M., de Vries, W., Sterck, F., 2023. The sustainability of timber and biomass harvest in perspective of forest nutrient uptake and nutrient stocks. Forest Ecology and Management 530, 120791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120791

Wuyts, K., De Schrijver, A., Staelens, J., Gielis, L., Vandenbruwane, J., Verheyen, K., 2008a. Comparison of forest edge effects on throughfall deposition in different forest types. Environmental Pollution 156, 854–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2008.05.018

Wuyts, K., De Schrijver, A., Vermeiren, F., Verheyen, K., 2009. Gradual forest edges can mitigate edge effects on throughfall deposition if their size and shape are well considered. Forest Ecology and Management 257, 679–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.09.045

Wuyts, K., Verheyen, K., De Schrijver, A., Cornelis, W.M., Gabriels, D., 2008b. The impact of forest edge structure on longitudinal patterns of deposition, wind speed, and turbulence. Atmospheric Environment 42, 8651–8660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.08.010

This Chapter is published on the EUROSILVICS platform, established as part of the EUROSILVICS Erasmus+ grant agreement No. 2022-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000086765.

R.V. was funded by an internal KU Leuven grant (C3/22/005) and FWO-postdoc (12AAE26N) during the drafting of the Chapter.

Author affiliation:

|

Van Der Bauwhede Robrecht |

KU Leuven, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, BE |

|

De Schrijver An |

HOGENT, BE |

|

Wuyts Karen |

INBO, BE |

|

Hartmann Peter |

FVA, DE |

|

Muys Bart |

KU Leuven, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, BE |

|

Mohren Frits |

Wageningen University, NL |